When Brazilian judoka Felipe Kitadai won bronze in the 60kg category at the London Olympics, he vowed to take his medal everywhere — even to the bathroom.

Yet Kitadai’s enthusiasm was soon dampened when, less than 24 hours later, having entered the shower and placed the 400g medal between his teeth to prevent it from getting wet, it proved too heavy and fell to the ground, shattering the fixture through which the ribbon looped. “The feeling I had when I saw the broken medal was like a child seeing his toy stop working,” he said.

Kitadai was provided a replacement by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), although he did not appear to have immediately learnt his lesson: “I will continue doing everything with it. I will not remove it when it’s time to eat, time to sleep or time to train with my teammates. And I will continue taking it with me at bath time, but now I will be more careful.”

Given an Olympic medal can represent a lifetime of effort, it is little surprise that some athletes should be inseparable from their prize. Should it get damaged — or worse — lost, replacements are almost always requested. The IOC say they receive two or three requests every year for substitute medals. According to the United States National Olympic Committee, a replacement medal can cost between US$500 and US$1,200 (Dh1,830 and Dh4,400).

Such sums are drastically more than the actual value of the medals, which have been alloys since the 1920 Games in Antwerp. The 1912 Olympics in Stockholm marked the last time a medal was 100 per cent gold and current IOC regulations require golds need only consist of 92.5 per cent silver and six grams of gold. “Being made entirely of solid gold is unrealistic nowadays,” said Victor Hugo Berbert, the man in charge of medal production for Rio 2016.

A gold at London 2012 — made up of just over 1 per cent gold, 92.5 per cent silver and 6.5 per cent copper — was worth approximately $625, while the bronze medal Kitadai damaged consisted of more than 98 per cent copper and thus held a value of less than $5. This year’s medals in Rio, although weighing 100g more, are worth less because of the depleted price of commodities.

Yet, naturally, no price can be put on the intangible elements that go into an Olympic medal: the blood, sweat and tears. Four years ago, British rowers Alex Partridge and Hannah Macleod had their bronze medals stolen after leaving them in their Team GB jackets inside a London nightclub. While Macleod’s was eventually recovered, Partridge’s remains missing.

“I always say to people: It’s not about the medal, it’s about the journey,” Partridge said. “It was only when I picked up my 16-month-old daughter from nursery that it dawned on me: if it doesn’t come back, she won’t see everything I worked for.”

He has since received a replica from the IOC.

********************************************************************

Two hours north-west of Rio de Janeiro’s famously thronged beaches, inside a sprawling complex protected by barbed wire and armed guards, sits the Casa da Moeda do Brasil. As well as annually producing more than five billion Brazilian Reals (Dh6.2bn), the country’s minting factory has also been secretively stockpiling the IOC’s requested 5,130 medals ahead of next month’s Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The Brazilian mint won the project in 2014, but the precise designs for this year’s medals were kept under wraps until only a couple of months ago. Such was the confidential nature of the process, the 100-plus staff were instructed not to speak about their work with family and friends.

Shortly after the June unveiling of the medals by IOC president Thomas Bach, however, The National was invited to tour the factory and gain a rare insight into the process that turns molten metal into the most desirable objects in world sport.

The IOC insists every gold, silver and bronze must include a likeness of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. Nelson Neto Carneiro, a veteran sculptor who has worked at the Casa da Moeda since 1974, was the man handed the responsibility of creating the cast of the deity.

“Even with all the technology of today, nothing can match the sensitivities of hand-design,” said the Brazilian, who uses a thin spatula to delicately sculpt the design in clay. “I gave Nike bigger thighs and hips, like the body of Brazilian women.”

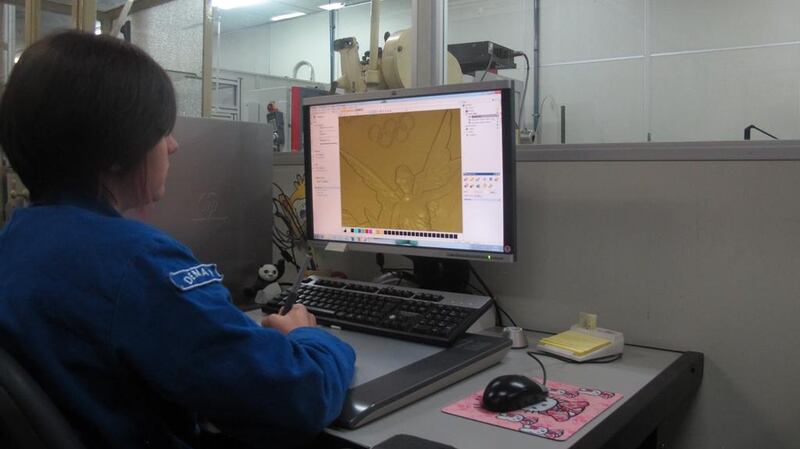

Once Carneiro completes his design, it is scanned by a 3D printer and sent to a three-person team who electronically add the surrounding detail: the Olympic rings, the wording — “XXXI Olimpiada Rio 2016” — and the traditional laurel leaf.

These finished designs — the front and back of the medals — are then sent to casting, where a high-powered engraving machine drills the designs on to a steel block that is later used as a matrix.

Technical operator Bruno Henrique da Silva Lobo performs the final check on the metal moulds, examining each with a microscope to ensure no defects.

“You won’t see it with the naked eye, but even the slightest flaw spotted under the microscope means we must create the entire matrix again,” he said.

To create 5,130 identical medals, the factory made 70 casts, 30 of which were immediately discarded due to minuscule defects. “In my line of work, perfection is the only result we deal in,” he added proudly.

In a building less than a javelin-throw from da Silva Lobo’s workspace is a high-ceilinged room that contains a cauldron filled with bubbling, spitting, molten metal. A nearby computer records the temperature of the contents at 1,338° Celsius. The viscous liquid is divided into 6kg alloy bars, before being flattened, compressed and cut into 500g circles.

Roughly 2.5 tonnes of metal have been used to create what are being billed as the most sustainable medals in Olympic history. According to Berbet, the head of medals, the silver consists of 30 per cent recycled materials “such as broken mirrors, X-ray plates and old car parts”, while 40 per cent of the bronze was taken from “old piping and electrical bars found inside the factory”. Fifty per cent of the ribbon material is made from recycled plastic bottles.

Each blank medal is placed between the two casts and struck three times with a force of 600 tonnes, or the weight equivalent of 150 single-deck buses. The silver and bronze medals are completed first, engraved with the name of the sport and category, and coated with a special protective lacquer. The gold medals — which contain only six grams of mercury-free gold and are thus silver in colour — require one additional step.

“At this stage, to the naked eye, the silver and gold medals appear the same, so the gold ones must be electroplated, to give them the right colour,” Berbet explained.

Idelberto Marinho do Rosario is the man with the Midas touch, tasked with turning the silver alloy into shining gold. Dressed in a white apron and blue latex gloves, he washes two silver-coloured medals under a tap before submerging them in an electrified tank of transparent solution. Four minutes later, when he removes them, their colour has transformed. The newly gold-plated medals are then lacquered and placed in a refrigerated drying chamber.

Once the medals are ready, the ribbons are attached and the finished articles are slipped inside a wooden case before being sealed inside in dated, pre-addressed boxes ready to be dispatched to the appropriate venues by Brazilian mail. The entire production process will continue until July 31, just six days before the start of the Olympics.

The medals for the Paralympics, which start on September 7 and run for 11 days, are slightly different in that, for the first time, they include a ballbearing mechanism so visually impaired athletes can differentiate between gold, silver and bronze. They also each have the words “Rio 2016 Paralympic Games” written on them in Braille.

Although the IOC have earmarked 2,488 medals for the Olympics and 2,642 for the Paralympics, the actual number of medals handed out is expected to be less. The governing body routinely request a “small number of spares”, said Berbet, presumably in case an overexcited athlete should have an accident after deciding to take their new medal for a shower.

Follow us on Twitter @NatSportUAE

Like us on Facebook at facebook.com/TheNationalSport