The 2010 World Cup got off the mark with a screaming left-footed drive at Soccer City on June 11. It finished with a nicely taken right-footed volley a month later. Between the ice-breaking pile-driver struck by the dreadlocked Siphiwe Tshabalala, of Kaizer Chiefs and South Africa, and the history-maker converted by the porcelain-faced Andres Iniesta, of Barcelona and Spain, the tournament produced 142 goals, excluding those converted in its two penalty shoot-outs.

That is a relatively low return for a World Cup of 32 teams. Some cited the ball: if every poor finish that was blamed on the Jabulani were given the value of a goal, then it would have been the most prolific World Cup of all. The effect of altitude on aerodynamics, and, yes, a light, occasionally eccentric ball may have hampered some players early in the competition. But there were sufficiently strong finishes from distance, notably from Uruguay's Diego Forlan - one of the few senior players who spoke out, before he began to start scoring goals with it, in favour of the Jabulani - that we should look elsewhere for reasons why South Africa 2010 had the lowest goals-per-match yield since of any World Cup since 1990.

Part of the explanation came from the first week, where a caginess governed, a palpable fear of losing the first fixture. The first round of matches in the group stage produced six draws and six 1-0s. Only Holland, Germany, Brazil and South Korea started their campaigns with more than one goal. As for the eventual champions, they failed to score, and lost, on their first matchday. Spain were hardly prolific afterwards: They scored eight times in seven matches, and en route to the final David Villa and Xabi Alonso each contrived to fluff a penalty.

What Spain had in common with several other sides was an a out-of-form striker. Fernando Torres looked rusty ? just like a player who had spent nearly three months sidelined after surgery on knee problems sustained while representing Liverpool. Torres had the alibi of injury. Wayne Rooney less so. The leading English scorer in the English Premier League had a wretched, barren and brief World Cup. The leading scorer of the Spanish league, Lionel Messi, curiously, did not score at all in South Africa, though he had plenty of influence on his Argentina team.

Other reputed marksmen whose reputations were hardly burnished in South Africa: Portugal's Cristiano Ronaldo (one goal), and Holland's Robin Van Persie (one); and others who left rather early: Italy's Antonio di Natale (one goal), Samuel (one). When a World Cup does not put the game's poster boys up on its highest podium, a first instinct is to say it shows that club football is superior to the international game. The loudest voices behind that argument tend to be club managers. It is self-evident that World Cups wage a battle against fatigue, coming as they do after 10 months of club work.

Even Forlan, named the player of the World Cup, admitted to feeling it at the end of a 12 months involved in La Liga and two different European competitions, one of them taking his Atletico Madrid all the way to the final. Nor is it coincidence that the sides most praised for their fresh approaches were Ghana, almost none of whose first XI players had been involved in long European club runs between last August and this April, and Germany, whose stars included Miroslav Klose, rarely used for 90 minutes by Bayern Munich. Most of all, Germany and Ghana were young teams, with higher reserves of stamina.

The team that drew from fewest different elite clubs won the tournament, too, Spain's football echoing and borrowing heavily from systems and strategies ingrained into the Barcelona players. The number of goals do not make a World Cup good or bad. Italia '90, which had few, was ugly, often dull and led to important law changes designed to rejuvenate and clean up the sport. South Africa 2010, whose knockout stages saw the goal-average increase, will not do that as radically, except if it prompts use of video technology.

The football on display from the Highveld to the Atlantic and Indian Ocean coasts confirmed rather than reshaped tendencies in the modern game: twin central strikers are largely out of fashion; but that does not always mean wingers are back in - one of the purest of this species, Angel di Maria, of Argentina, had a quiet tournament overall. And if they are, they are often used on the flank that encourages them to cut inside, like the left-footed Arjen Robben, of Holland or Dede Ayew, of Ghana.

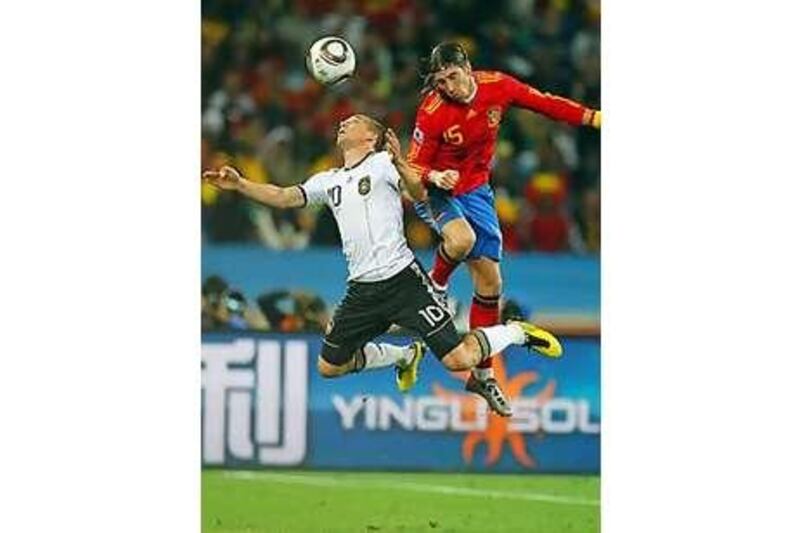

Attacking full-backs came to the fore, like Spain's Sergio Ramos, Portugal's Fabio Coentrao, Brazil's Maicon and Ghana's Samuel Inkoom. And no longer can the anchor midfielder, while still deemed essential by most coaches, be merely a tackler and a bruiser. Bastian Schweinsteiger of Germany showed that; Holland were eventually limited because they sought enforcement rather than enterprise in that area of the pitch.

@Email:sports@thenational.ae