On September 26, 1962, the millennia-old Yemeni imamate came to a sudden, if not wholly unexpected end.

Seven days prior, Imam Ahmed, who succeeded his father after his assassination in 1948, had died in his sleep. Barely a week after taking the reins of power, his son, Mohammed Al Badr, found himself under siege, as rebellious military units commanded by Col Abdullah Al Sallal, the newly appointed commander of the palace guard, shelled his Sanaa residence. As the palace was reduced to rubble, a string of triumphant radio messages went out, announcing the end of the imamate.

For about a year now, I’ve been making weekly visits to one of the main men behind those messages, a 70-something retired Yemeni diplomat named Abdulwahab Jahaf. The events of September 26 are rarely mentioned but always present – gestured to in photos perched on various shelves on the wall, which track my friend’s rise to prominence as a revolutionary and his subsequent career as Yemen’s ambassador to Libya and Qatar.

They loom like spectres as we while away the afternoon and early evening, chewing khat and discussing whatever topic seems appropriate, as Yemeni men are wont to do, bringing context to debate over the present and tacitly underscoring points made during conversations about the not so distant past. They often seem more sentient than static, provoking different thoughts and reactions depending on the events of the day or the talk of the hour.

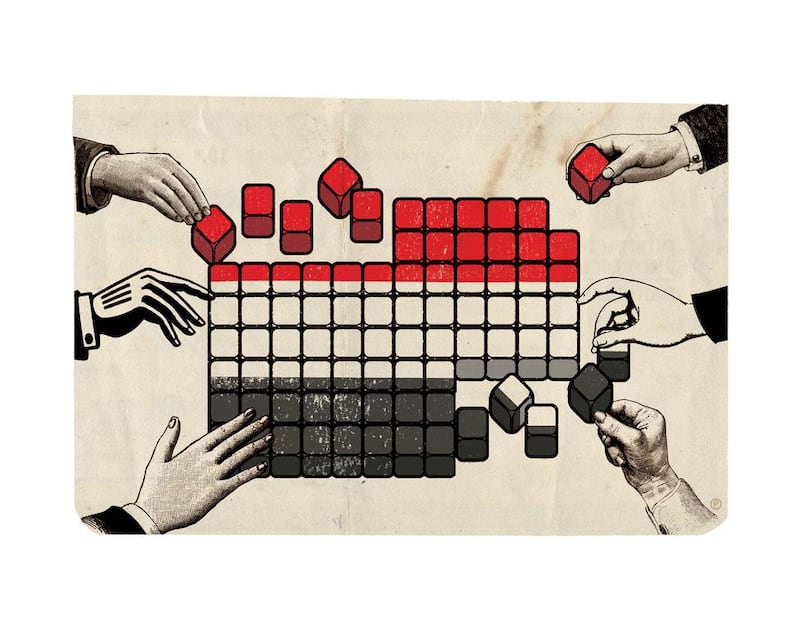

It’s rather fitting, considering the general way history tends to function here. Far from settled, the past often seems to be treated as an extension of the arena of continuing factional squabbles. Even outside of that, though, the past ultimately tends to feel as muddled as the present. Competing narratives are inescapable and – regardless of whether history books tend to lean one way or the other – unavoidably relevant.

Such conflicts are endemic even in the two events that are generally held to herald the birth of modern Yemen: the fall of the imamate in the north and the end of the British presence in the south. Written as such, they seem like liminal dots on a timeline. Hearing Yemenis discuss them, however, they often feel as fluid as the events of the present day.

That is even – perhaps particularly – true when the people in question were directly involved. Splitting the two sides in the September 26th revolution and the civil war that followed into separate camps of “royalists” and “republicans” tends to feel simplistic at best. It often feels like there is as much debate over the motives of tribal leaders who backed the revolution of 1962 as there is regarding those who backed Yemen’s revolution of 2011. Even many of those who fought on the side of the royalists baulk at being cast as such.

The blurred lines were evident in the reactions spurred when I noted a photo of the former Yemeni president, Abdulrahman Al Iryani, exiting a plane with Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat – and, off in the background, my friend Abdulwahab – early one afternoon at his house. I was clearly a bit star-struck – the photo seemed to epitomise the way my friend has been a witness to history, to the winds of change sweeping the Arab world at the time

But for another septuagenarian friend present, who defected from the republican camp to fight with the royalists during the war, the photo had a different meaning. He launched into a description of the intervention of various international actors in north Yemen’s civil war, centring on the deployment of tens of thousands of Egyptian troops and their use of chemical warfare.

“The royalists, Mohamed Al Badr? We knew them, we understood them. I figured we could deal with them later,” he said months later, explaining his decision to defect. “But the Egyptians were different – for me, what was important was getting these foreigners out of my country.”

Such discussions rarely limit themselves to the war itself. Discussions of Egyptian interference tend to shift to ones over Saudi interference and, the way many Yemenis tend to tell it, the eventual end to hostilities ends up overshadowed by debates over the events that followed. Was Mr Iryani, the man at the top when the dust cleared in 1970, a man of principles or a man who was too weak to lead Yemen at such a critical time? Should Ibrahim Al Hamdi, who succeeded Mr Al Iryani after a military coup, be remembered for his role in removing north Yemen’s only civilian president or for his ambitious vision for Yemen, never realised because of his assassination in 1977? Did Mr Saleh’s 1978 accession to power usher in a period of stability or decades of corrupt autocracy?

The changes under way in the southern half of a then-divided Yemen at the time were arguably even more dramatic – in the space of roughly a decade, the southern port of Aden went from being an outpost of the British Empire to the capital of a USSR-aligned Marxist state.

The same goes for the discordant ways in which such events are viewed. Figures cast as forward-thinking, quasi-heroic revolutionaries by some are maligned as vicious murderers by others. Cold-War politics are treated as everything from crucially important to nearly tangential. The two Yemeni states’ eventual 1990 unification can represent everything from a historic triumph to a disastrous mistake.

Even recent events seem to be nearly universally muddled. Depending on whom one talks to, the events of 2011 amounted to a revolution that deposed Mr Saleh or a political crisis resolved by his decision to leave power.

Rather than just learning a single chronology, grasping Yemen’s history seems to centre on digesting and reconciling a series of competing narratives. To some extent, I guess that’s true everywhere. Still, going about the process of understanding and contextualising events here often feels like a matter of life and death. At times I feel like working as a western journalist in Yemen is akin to having been dropped into a room of people in the middle of a deep argument and immediately trying to understand the truth. I’m still uncertain about what the argument is actually about.

Oddly, my afternoons at my friend Abdulwahab’s house have provided a surprising source of comfort. Watching a bunch of men in their seventies debate events that happened decades ago does a decent job of putting current uncertainties in context. More importantly, whether they’re dealing with the past week or the past century, the discussions are always fascinating and the welcome is always warm. I’m still a bit astonished that they’ve gladly allowed an American journalist a third their age into such a close-knit circle.

Still, when it comes to my turn to contribute, I often find myself trembling with fear. On the one hand, it’s a compliment simply that they’re curious to hear my take on the current state of things or where they seem to be heading. But when the past is so contested, it feels almost arrogant to speak in concrete terms about the present. Making predictions about the future seems foolhardy at best.

Adam Baron is a freelance journalist based in Sanaa

On Twitter: @adammbaron