The unprecedented breakdown of relations between the US and Pakistan, as the end game begins in the war in Afghanistan, is a result of the far larger and more dangerous political and economic crisis that besets Pakistan's military and civilian elite.

This internal crisis has been exacerbated by paralysis of will and lack of political courage; the leadership will not take the now well-documented measures necessary for major political, economic and foreign policy reforms that have been pending for 20 years, since the end of the Cold War.

For over a year, Pakistan's litany of complaints towards the US, and corresponding complaints by the administration of the US president, Barack Obama, have damaged relations so badly that some American congressmen are contemplating a cut-off of all aid to Pakistan, plus sanctions.

That would be a much worse replay of the 1990s, when US sanctions - imposed because of Pakistan's nuclear programme - also paralysed the relationship. This time would be worse because Pakistan was much stronger then; now it faces a meltdown on several fronts.

The US accuses Pakistan's military of playing a double game by officially fighting terrorism but also providing sanctuary and support to the Afghan Taliban and refusing to clamp down on the network of the Taliban leader Jalaluddin Haqqani, which operates openly from Miranshah in South Waziristan.

And there is still no answer to who was providing support to Osama bin Laden before he was killed last year. That operation, by US special forces, led Pakistan to accuse the US of violating its sovereignty.

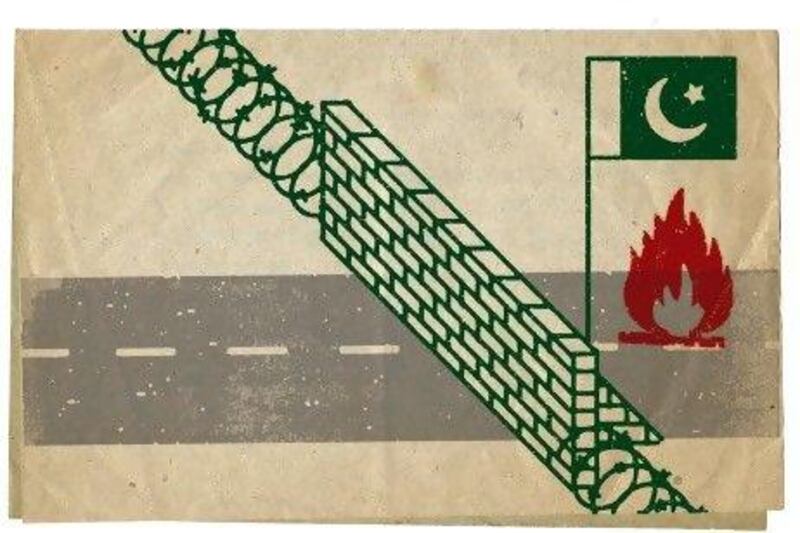

Then, last November, a US attack killed 24 Pakistani soldiers on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Pakistan responded by closing the road from Karachi to the Afghan border to Nato supply vehicles, a closure now seven months old. In the latest twist, Pakistan is offering to open the road - at a fee of $5,000 per lorry - a price the US defence secretary, Leon Panetta, has called extortion.

Pakistan is also demanding an end to US drone strikes, but drones are the main US counter-terrorist weapon in Pakistan.

On Thursday, in Kabul, Mr Panetta sounded even tougher, saying the US is "reaching the limits of out patience" over safe haven in Pakistan for Afghan terrorists.

The US-Pakistan crisis has been fuelled by increasingly louder anti-Americanism voiced by the public. Many Pakistanis blame the US for their country's major domestic ills, and the US military presence in Afghanistan for the increasing Talibanisation of the region.

Anti-Americanism has also been fuelled by the military, its Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and some politicians. Finger pointing is easier than answering the Pakistani people's questions to the establishment about the risk of state failure.

The military has also encouraged extremist groups, Islamic fundamentalist parties and Sunni sectarian groups, to unite for anti-American rallies. Now that the government is trying to talk to the Americans about reopening the road, it finds it is trapped by these same activists: their demands have escalated and the anti-American mood in the country is more pronounced.

Both the army and the government lack the courage or will to take the tough decisions. Both have become hostage to their own policies.

This lack of will reflects the primary crisis Pakistan faces, which is wholly internal and due overwhelmingly to two decades of gross mistakes by the ruling elite, not solely to American perfidy.

Four forces in Pakistan - the army, the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party, opposition parties and a recently empowered judiciary - have all been pulling in different directions for over a year, destabilising the fledgling democratic political system.

At times the army has joined hands with the judiciary to try to topple the government through legal judgements. The opposition threatens stalemate. The government itself, considered hopelessly corrupt and incompetent, blunders badly and fails to maintain law and order.

At the same time the economy has deteriorated swiftly. This is partly because of a critical energy crisis; electricity and gas shortages have led to widespread rioting and the collapse of industry and agriculture. Another factor is the government's failure to carry out major reforms in revenue collection, in ending subsidies and in favouritism to the military. All of these have been undermining Pakistan since the end of the Cold War.

At that time 20 years ago India, Bangladesh and other countries in the region carried out economic reforms and geared their foreign policy to building trade and investment ties with their neighbours.

Pakistan's military, on the contrary, spent much of the 1990s indulging in two covert wars - supporting the Kashmiri separatist movement against India and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Pakistan's foreign policy, as conducted by the military, has been dominated by the use of extremist groups to fight proxy wars with Pakistan's neighbours. This undermined any hope of economic reforms or major external investment.

Using extremists as a tool of foreign policy stopped, in most of the region, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. But Pakistan continued the practice, and went on sustaining such groups even after the attacks of September 11, 2011, when there was no longer any excuse to support Islamic extremist groups.

This policy strengthened extremist groups inside Pakistan, and the eventual result was the Pakistani Taliban. This proximity to terrorism, and the lack of political alternatives, have accelerated the breakdown, increased the lack of accountability in the army and police and also encouraged nationalist and separatist groups in Balochistan province and most recently in Sindh province.

A spate of attacks against minority religious groups, by Sunni extremists, has also gone unchecked. These have targeted Hindus and Christians but also certain Muslim groups: Ahmedis, Ismailis and Shias in general.

In Karachi, the breakdown of order is leading to the growth of armed militias based on ethnic, criminal or political loyalty. There is now a no-holds-barred campaign against the army, including torture and executions, by Baloch separatists and the Pakistani Taliban. The military retaliates with equal brutality, in an unchecked spiral of violence.

The failure of the politicians to work on dialogue and reconciliation only increases the use of the military as the only problem-solver. The result is ever-escalating violence.

All these problems have been exacerbated by the war in Afghanistan, the 130,000 western soldiers there and the demands by the US and Nato that Pakistan stop giving sanctuary to the Taliban. Pakistan's military has retained the Taliban for precisely this end game - to use it in peace talks with the Kabul government and the Americans.

At the precise moment when Pakistan's army wanted to be in a commanding position, however, as the US starts its pull-out from Afghanistan, the army finds its relations with the US totally disrupted. The Americans have effectively bypassed Pakistan by starting their own dialogue with the Taliban. This has caused both anguish and anger in the Pakistani military.

Given Pakistan's growing international isolation and the general western distrust of its leaders, it is hard to see how the military will agree to give up its Taliban proxies.

The US and the West will have to exercise great patience in dealing with Pakistan, first helping to resolve at least some aspects of the country's internal crisis.

The government needs to bring forward next year's elections, and if it is voted out of office as expected, then create a peaceful transfer of power to the newly elected government and allow for a new political dispensation.

The government must also announce plans to reintegrate Islamic groups into the political mainstream and provide militants with new skills, training and education.

Pakistan badly needs a major makeover but bringing that about is still fraught with difficulties, due largely to the reluctance of political and military leaders to take the tough decisions that are needed.

Ahmed Rashid has published five books on Afghanistan, Pakistan and Central Asia. His fifth, Pakistan on the Brink: The Future of America, Pakistan and Afghanistan, has just been released by Viking Penguin

Pakistan's prickly paralysis fuelled by legacy of delusion

This lack of will reflects the primary crisis Pakistan faces, which is wholly internal and due overwhelmingly to two decades of gross mistakes by the ruling elite, not solely to American perfidy.

Editor's picks

More from the national