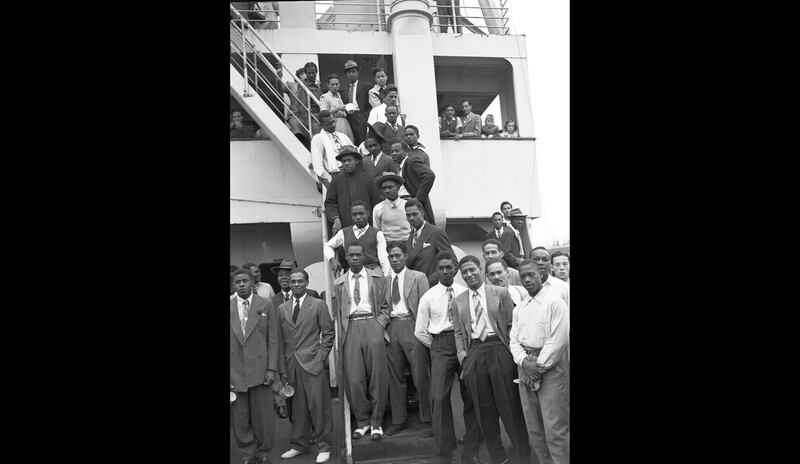

We hear of Africa, and of Africans and their descendants, because the demands that countries re-examine their histories of empire and colonialism have focused in particular on the transatlantic slave trade. Given that the protests worldwide were sparked by the injustices black people in the US still face today, that is understandable, as is the fact that this means it has been the records of Europeans in Africa and America that have been held up to the light.

But if former imperial powers are truly to face up to the reality of their pasts, we must also hear of Asia. The cold truth of colonial rule and interference on the continent, and its long-term consequences, must also be taught widely. This is because, while we can debate whether the sins of the fathers should be borne by generations who come long after, people today should at least be fully informed of how these ancestors affected their own countries' histories and frequently afflicted those of others.

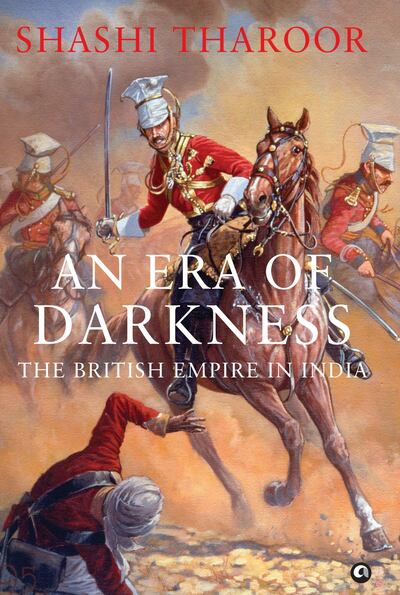

How many, for instance, are really aware of the huge transfers of wealth from Asian colonies to the imperial homelands? The Indian politician and former UN undersecretary general Shashi Tharoor has written powerfully of how the British conquered one of the richest countries in the world and reduced it to one of the poorest. "At the beginning of the 18th century, India accounted for 23 per cent of global GDP. When the British left it was down to barely 3 per cent," he wrote just before the publication of his 2016 book An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India.

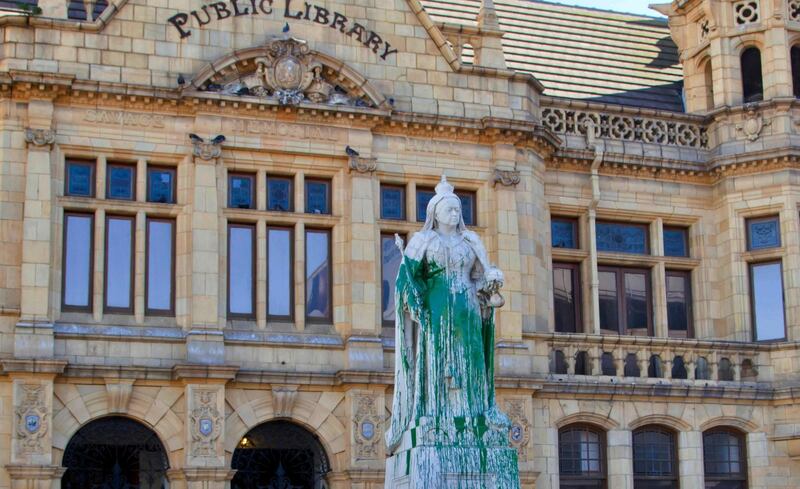

One can talk about standards of the time, and how historically most countries had sought land and treasure; but even by the mores of the 18th century, the atrocities and robbery perpetrated by Robert Clive as he established British rule in India made him "widely reviled as one of the most hated men in England", in the words of the historian of the East India Company, William Dalrymple.

Unwanted foreign interventions have long-term effects still felt today. In most parts of Asia, Britain kept local rulers in place, even as they imposed one-sided treaties upon them that left them with colonial “advisers” who in fact wielded the ultimate power. But in Myanmar Britain abolished the monarchy after winning the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885 and sent the last king into exile. Many historians feel that Myanmar’s tragic post-independence history might have been different if the stability and unity that the royal institution provided had remained in place.

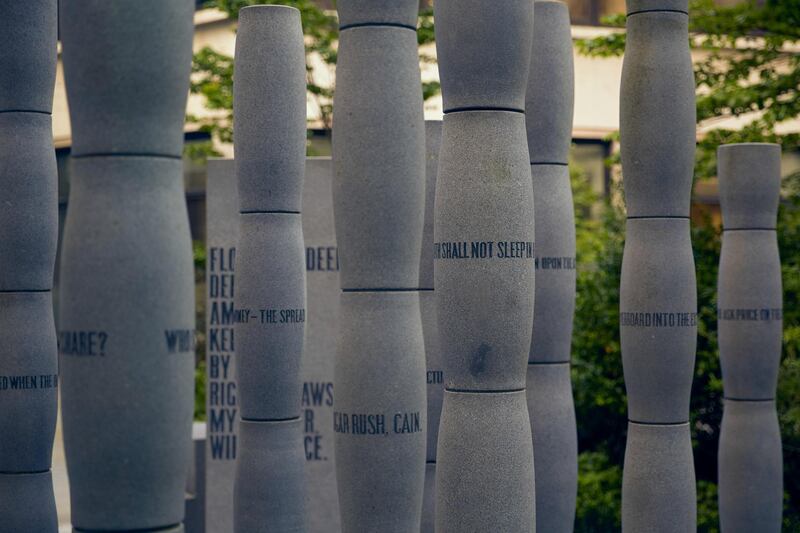

The boundaries of countries were often written by imperial powers.

In south-east Asia this led to the construction of two states, Malaysia and Indonesia. For there had never been two countries thus named in the past. They were both part of Nusantara, the vast Malay archipelago in which empires such as Srivijaya and Majahapit had risen and fallen. It was two treaties signed by Britain and the Netherlands in the early 19th century dividing their spheres of influence and colonial possessions in the region that effectively created them.

That may not appear to have had the most malign of consequences, but the division sundered communities and a historic sultanate. Who is to say what kind of polities might have emerged if the peoples of those lands had decided for themselves?

Other boundaries named after Europeans, such as the Durand Line dividing Afghanistan and Pakistan and the McMahon Line between China and north-eastern India, have long been troublesome, regarded by various parties as either arbitrary or disputed. And in the Middle East, the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement by which France and Britain agreed to share out much of the Ottoman Empire has become a byword for the follies of outsiders presuming to decide the fates of others, and instead plaguing the region with instability for decades to come.

Whatever they proclaimed, the imperial powers did not arrive with the good wishes of local peoples at heart. They believed they were racially superior and demanded adherence to their rulings. For all that France claimed that its colonial policy was driven by a “mission civilisatrice”, or civilising mission, it did not stop it enforcing its will by arson, torture and mass killings in French Indochina – modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

America’s behaviour in the Philippines was more deceitful. The leaders of the Philippine Revolution thought they had been promised US support if they managed to eject their Spanish colonial masters. But after the Filipino leadership declared independence in 1898, American troops occupied the islands to “protect the Filipinos” and “tutor them in American-style democracy”, in the words of one US senator.

How much of this is recalled today? Worse, much of the history of Asia has long been taught from a very western perspective. General Clive was regarded as a hero when I learned about him at school, having been subject – as I did not know then – to reinvention as a swashbuckling imperial adventurer in the early 20th century.

The war crimes committed by the Japanese in the Second World War have been commemorated in popular culture as having been perpetrated almost solely against white Allied soldiers (the racist subtext being that this was particularly terrible). To take one: the Burma Railway, on which prisoners of war were forced to work in appalling conditions, was made famous by the book and film The Bridge Over the River Kwai. So many know that up to 15,000 POWs died as a result. Far fewer are aware that more than 100,000 local labourers also perished.

The list could go on and on. How many who cry so loudly for the rights of Hong Kongers to democratic freedoms, for instance, are fully conscious of the way Britain acquired the island from China in the first place?

So yes, tell the story of empire fully and truthfully – but also inclusively. Colonial horrors were inflicted not only on Africa but on Asia, too. None should be ignorant of them, as my colleague Shelina Janmohamed wrote recently, so that countries around the world know what they were then and what they are therefore today.

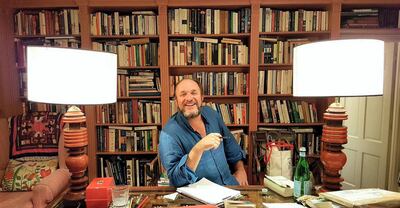

Sholto Byrnes is a commentator and consultant in Kuala Lumpur and a corresponding fellow of the Erasmus Forum