Every few months, a UN envoy seeking a political solution to the Syrian civil war briefs the Security Council on what has been described as a lack of any significant progress.

Geir Pedersen's mission, to implement international resolutions calling for undefined political transition in Syria, now faces even more challenges after Syrian President Bashar Al Assad gave a television interview this week with Sky News Arabia.

The president blamed neighbouring countries for the chaos in Syria, as well as a buoyant illicit trade in a type of amphetamine known as Captagon. He made no mention of the possibility of a change of his family's rule over a government, which has lasted 53 years.

Civil war began towards the end of 2011, after authorities repressed peaceful demonstrations against Mr Al Assad. Iran, Russia, the US and Turkey carved out zones in the country, funding proxy militias and fighters, from Marxist-Leninist guerrillas to Sunni and Shiite extremists.

The Russian intervention in 2015 was crucial to Mr Assad maintaining control in Damascus.

The smuggling of narcotics across to neighbouring states, mainly to Jordan, became a lucrative business for his loyalists and a main supply of foreign currency.

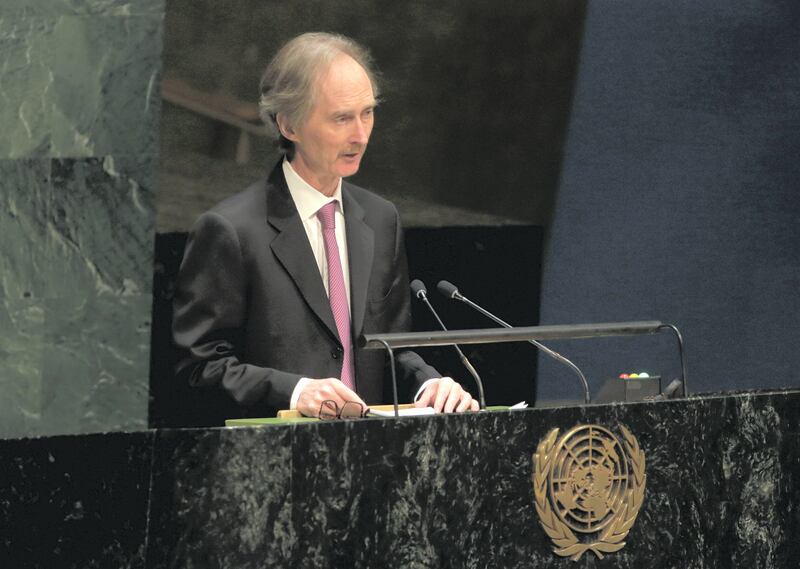

Mr Pedersen, a Norwegian diplomat, is persisting in his efforts and has not given up as his three predecessors did.

“Pedersen is still there because he recognises that any solution is not in the hands of Assad,” Khaled Helou, a member of the Syrian opposition who sits on a dormant, UN-supervised committee formed four years ago to come up with a new constitution, told The National.

Two of Mr Pedersen's predecessors, veteran Algerian diplomat Lakhdar Brahimi, and the late former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, were some of the most distinguished names in international diplomacy in the past half century.

Mr Brahimi engineered the 1989 Taif Accords that helped end the Lebanese civil war but failed to loosen Damascus’s influence. He succeeded Mr Annan as Syria envoy and quit in 2014, the year the UN peace process started in Geneva.

UN envoy spokeswoman Jenifer Fenton told The National Mr Pedersen continues to “to engage with all relevant actors, and explore and test possibilities for diplomatic traction on all aspects of his mandate”.

His mission for political transition in Syria is one of three international diplomatic tracks.

The second is a Russian-supervised peace process in Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan.

The Astana process consists of Moscow, Iran – Mr Al Assad’s main regional supporter – and Turkey.

Delegations from the Syrian government and the opposition attend but their presence is mostly symbolic, with the big powers deciding on any outcome.

But Ankara has eased its opposition to Mr Al Assad over the past two years, partly to undermine Kurdish militias that had acquired, with US support, territory on its border in north-eastern Syria.

The north-east forms the bulk of the US zone in Syria, which mostly runs along the border with Turkey and Iraq.

Turkey is also engaged with representatives of Mr Al Assad in a third, stalled track focused on finding ways to undermine the US zone of influence in Syria. The talks are overseen by Russia and attended by Iran.

In this fragmented landscape, Mr Pedersen has had to operate, with the US having acquiesced in 2015 to a takeover by Moscow of the international diplomatic file for Syria.

Mr Helou said Russia, with co-operation from Iran and Turkey, would have imposed a “cosmetic” political solution to the Syrian civil war that strengthens the regime in Damascus had it not been for last year’s invasion of Ukraine.

Since that began, “Washington has mostly stopped playing ball with Russia over Syria”, said Mr Helou, a former judge who fled Syria to Turkey after the government unleashed its security forces and sent tanks into cities to suppress the revolt in 2011.

“Assad does not seem to have grasped that the international picture has changed after the Ukraine war,” Mr Helou said.

“He does not recognise how weak he is and that if the United States and Russia ever agree, a solution will be imposed, whether he wants it or not,” he said.

Arab turnaround

Arab countries, some of which have supported anti-Assad rebel groups, largely withdrew from the Syria file after the 2015 Russian intervention.

With Russian encouragement, and because of a Saudi detente with Iran, most welcomed back Mr Al Assad into the Arab League after more than a decade of isolation.

Countries have different reasons to accommodate Mr Al Assad, with Jordan hoping for a reduction in Captagon flow and gestures to welcome back refugees. Other countries appear to have more geopolitical interests in mind, relating to better ties with Iran and a possible deal between Ankara and Damascus.

But the US and other western powers have opposed re-establishing diplomatic ties.

Middle East specialist Mona Yacoubian says the so-called normalisation complicates Mr Pederson's task, although he had welcomed it.

“Restoring ties and readmitting Syria to the Arab League were a huge concession, without apparently getting much, if anything, in return,” said Ms Yacoubian, vice president of the Middle East and North Africa centre at the US Institute of Peace, funded by the US Congress.

She said the move has dealt the UN peace process “another serious blow”, on top of Russia's “refusal to engage in Geneva”.

In his interview with Sky News, which was broadcast on Wednesday, Mr Al Assad mentioned the UN only when talking about the possibility of the return of the millions of refugees who had fled Syria.

But last month, Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi said after meeting Mr Al Assad in Damascus that UN resolution 2254, the core of Mr Pedersen's mandate, remains the basis to solve the conflict in Syria.

The resolution, passed six weeks after the Russian intervention, toned down past international deals that specifically called for a transitional governing body and the lifting of the heavy grip of the security apparatus in the country.

But it kept open the possibility for a transition of power in Syria, as well as reconciliation.

Bente Scheller, head of the Middle East division at the Heinrich Boell Foundation, said Mr Al Assad has no interest in triggering the resolution, nor in responding positively to the Arab gestures.

“So far the initial steps of the Arab states have not been reciprocated by the regime,” she said.

“In all the areas where the states from the region expected more co-operation, the situation has got worse rather than better.”

'Stonewalling'

A day before Mr Al Assad's interview was broadcast, police in Jordan announced the confiscation of a stash of drugs from a trading zone on the border with Syria, from where they were to be smuggled into the kingdom. The zone is jointly run by the two sides.

Ahmad Tumeh, a Syrian opposition figure who is close to Turkey, said Syrian government delegations had adopted a stonewalling tactic whenever the talks convene in Geneva, however seldom.

“They object to any proposal on the grounds that it undermines the sovereignty of the current government and brands any opposition as terrorists,” said Mr Tumeh.

“Their strategy is to sabotage the talks from within.”

Ultimately, he said, all the international powers appear content to leave intact the “existing lines of separation” in Syria, between the government, opposition areas and territory held by Kurdish militia.

Several weeks ago, Mr Pedersen, in an address to the UN Security Council, expressed hope of positive developments soon. He said that despite months of promising diplomacy, there had been no tangible results for the Syrian people.

Mr Pedersen appealed to Damascus to work with the UN in pursuit of a political path, insisting “a Syrian-Syrian track and a wider process of confidence building” were needed.