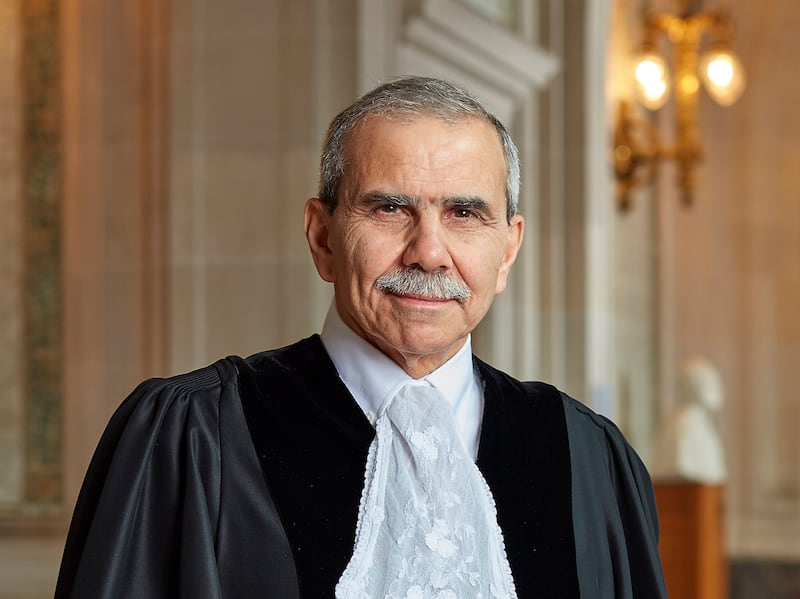

Beirut was among the first thoughts that crossed Nawaf Salam's mind upon being elected president of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a three-year term last week.

“I thought of my city, hoping for the day it will once again be hailed as the 'mother of laws',” the Lebanese judge told The National from The Hague in the Netherlands, where he lives.

He was referring to Beirut's status in ancient Rome as a prominent centre for the study of law. “Mother of laws” has remained the motto of Lebanon's capital and adorns the city's flag.

Centuries later, the country is grappling with a lack of accountability. Its political elites are seemingly untouchable; most of its high-profile judicial cases have stalled, from political assassinations to financial scandals and, most recently, the deadly 2020 Beirut port explosion.

Mr Salam, a member of the ICJ since 2018, is the first Lebanese and the second Arab to head the UN's World Court, created in 1945 to settle disputes between states.

“His election is a source of pride for many Lebanese,” said Ziad Majed, a Lebanese political researcher and friend of Mr Salam for 30 years.

Born into a prominent Sunni family from Beirut in 1953, Mr Salam is a jurist, diplomat and intellectual whose rich career has earned him credibility and respect internationally.

“Many in Lebanon are disillusioned by the challenges their country faces but often inspired by individuals like Mr Salam who strive to make a difference and succeed in international institutions. He has the qualifications to live up to the expectations,” he said.

'Heavy task'

Despite the praise, Mr Salam retains his humility: there is a “heavy task” awaiting him as the new ICJ president, he said.

“The court hasn't been this busy since 1945, with a multitude of cases with a clear political background,” he said.

He mentioned cases such as Armenia versus Azerbaijan, in which the former accuses the latter of ethnic cleansing; Russia versus Ukraine, where Russia is being tried for war crimes; and South Africa's historic genocide case against Israel over its war in Gaza.

Mr Salam declined to comment on the court's recent ruling in the genocide case, citing his duty of confidentiality.

Why the ICJ did not order a ceasefire in Gaza

The majority of the 17 ICJ judges hearing the case, including Mr Salam, voted for the court's interim order directing Israel to take measures to protect lives in the Palestinian territory.

Reactions to the court's decision were mixed. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu condemned it as “vile”. Some regretted the ruling did not call for a ceasefire, while others viewed it as a significant step, noting that its implementation effectively depended on a ceasefire.

“I invite you to read the indicated measures," Mr Salam said simply, confirming his full agreement with them.

The court order requires Israel to take measures to prevent genocide in Gaza and to allow badly needed humanitarian aid into the besieged territory.

Social justice at heart

Those close to Mr Salam describe him as a reformist and a moderate intellectual.

His friend, political scientist Karim Bitar, described him as a “well-read multidisciplinary intellectual, familiar with sociology, history and political science, and an avid reader, who always has a reformist bend and cares about Lebanon's Arabic identity”.

“He had the courage to distance himself from his traditional family. In his youth, he held a somewhat radical stance."

Many of his relatives played key political roles in Lebanon's history. His grandfather, Salim Salam, was the deputy of Beirut in the Ottoman parliament in 1912. His uncle Saeb Salam, who is regarded as one of the country's founding fathers, and his cousin, Tammam Salam, both served as prime ministers.

Despite his traditional background, he became involved in pro-Palestinian and leftist circles during his university years in the 1970s, a time when the world experienced a vibrant wave of student movements.

Mr Salam has since reflected on those years, marked by effervescent social struggles and left-wing ideas – followed, for many, by disillusionment.

“The youth in my generation prioritised the question of equality over freedom,” Mr Salam said. “But in a democracy, equality and freedom cannot be separated. That, I learnt through experience.”

Yet this period nurtured his strong sense of social justice, he said. His attachment to the Palestinian cause would never leave him either.

He began his teaching career in the late 1970s as history professor at the Sorbonne, then at the Harvard Law School in Boston and the American University of Beirut, where he taught international relations and law.

In the 1990s, alongside his teaching, Mr Salam dedicated himself to bringing about change in Lebanon, with a focus on transcending sectarianism towards a civil state, reforming the electoral code and the judicial system.

“Unfortunately, these reforms have not materialised," said Mr Majed. "At the time, the hegemony of the Syrian regime, sectarian divisions within Lebanon and regional alliances had sidelined reform efforts."

A decade of advocacy

In 2007, Mr Salam moved to New York, where he served for 10 years as Lebanon’s permanent representative to the UN.

“Having taught international relations for 20 years, it felt like an opportunity to bridge the gap between theory and practice,” he said.

During his term, he consistently advocated for respecting UN Resolution 1701 for border stability in south Lebanon, establishing the Special Tribunal for Lebanon for former prime minister Rafik Hariri's assassination and defending Palestinian rights.

“He played a crucial role in representing Lebanon during challenging times, particularly amid the Syrian crisis and various international interventions in conflicts while demonstrating his commitment to international law,” Mr Majed said.

In 2017, he was appointed a judge at the ICJ by the UN General Assembly and the Security Council.

An intellectual in politics

In the wake of Lebanon's 2019 economic collapse, which led to the resignation of several governments, his name has frequently been raised by opposition groups as an independent candidate for the position of prime minister.

In a 2021 book, he called for a “Third Republic” and the creation of a modern and civil state based on “the values of equality, freedom and social justice, rather than sectarianism and favouritism”.

Despite Lebanon's continuing crisis, wrecked financial sector and political paralysis, Mr Salam told The National he remains resolutely optimistic about his country's future.

His candidacy for prime minister was opposed by Iran-backed Hezbollah – the influential Lebanese party and militia viewed the diplomat as too close to Washington. Now, he is also under fire from the US staunchest ally, Israel. The Jerusalem Post labelled Mr Salam as “anti-Israel” after his election as the ICJ president.

Mr Salam never officially declared his candidacy and billionaire businessman Najib Mikati was eventually appointed prime minister in September 2021.

“Like most intellectuals in politics, Mr Salam tends to be overly cautious, always weighing the pros and cons of every option. If he had ventured into Lebanese politics, he probably would have garnered significant support and managed to rally a large segment of the opposition,” Mr Bitar said.

“This proved to be a wise decision. The position he occupies now is symbolically extremely important, and most Lebanese felt pride when he was elected.”