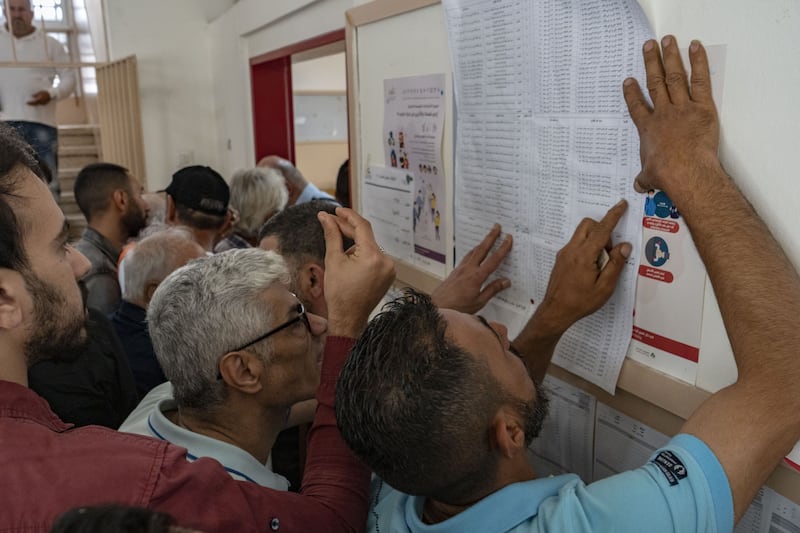

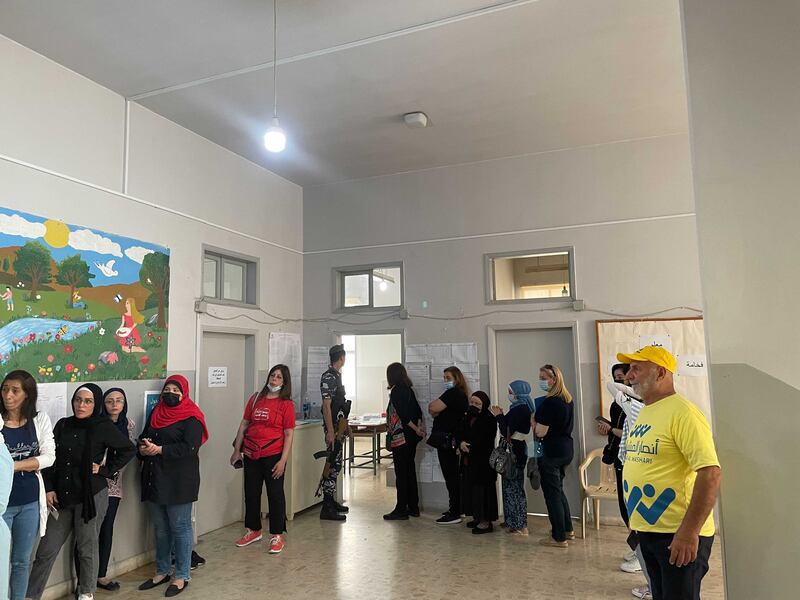

Voters in Lebanon’s second city of Tripoli offered a mix of reasons for their decision of whether or not to take part in Sunday's parliamentary election, ranging from hope to apathy and cynical opportunism.

Many in the Sunni-dominated city — the poorest in a country beset by economic crisis — said a failure to vote would strengthen the hand of Hezbollah, the powerful, Iran-backed Shiite movement, and its parliamentary allies.

Others said they would stay away from the polls because none of the candidates on offer — including those from opposition lists linked to the October 2019 protests against Lebanon’s ruling classes — represented their interests.

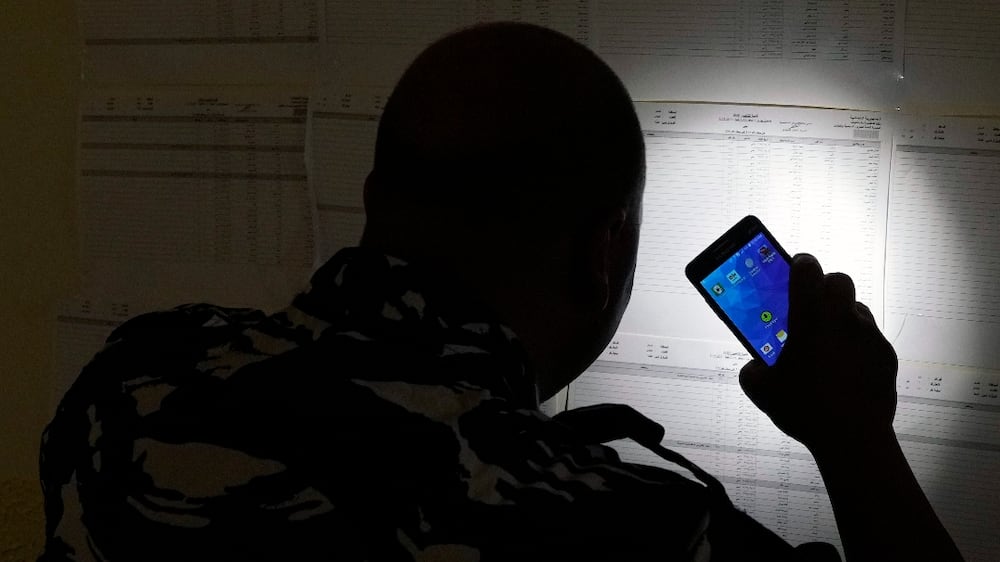

Lebanon's poorest city votes by torch as power fails

But all agreed that Tripoli — with its high levels of poverty and unemployment — was in dire need of change, as they expressed frustration at politicians who they say have done nothing for them.

“There have been bad changes that happened in the last four years; we can feel them,” said Fadi Arabi, a football coach, who did not vote in the 2018 general election.

“This made us more interested in voting, to change this situation we are living in. We are thinking about our children, we want a better future for our children.”

Mr Arabi said he was voting also to prevent Gebran Bassil, leader of the Christian-led Free Patriotic Movement and a Hezbollah ally, from strengthening his position in parliament.

The decision by Saad Hariri to withdraw his Future Movement — often seen as a bastion of the Sunni community — from the election and leave politics, led to fears that many Sunnis would abstain from voting.

The three-time prime minister cited the futility of running when Iran was so influential within his country. Some Future Movement members disagreed and are contesting the election on other lists.

One of the lists is sponsored by Prime Minister Najib Mikati, a billionaire businessman from Tripoli, although he is not contesting the election as a candidate.

For Mr Arabi’s brother, Samer, this is the first time he is voting, as until last year he was a member of the Internal Security Forces and was ineligible to take part. He said he had planned not to vote because of Mr Hariri's withdrawal, but later changed his mind.

“We are looking for change. We want to change how politicians are playing with people and their religion,” he said.

Lebanon’s economic collapse since 2019 sent the local currency crashing by more than 90 per cent and has plunged most of the population into poverty. But Tripoli was poor even before then, particularly the Sunni-dominated Bab Al Tabbaneh neighbourhood.

From 2011 to 2014, the city was rocked by sectarian violence as Syria's civil war between Sunni-dominated rebels and an Alawite-led regime was reflected in Bab Al Tabbaneh and the Alawite Jebel Mohsen neighbourhood, which are separated by a single street called Syria Street.

But the sectarian tensions had been brewing long before 2011, and continue today.

Ahmed Ibrahim, a 51-year-old driver, blames the politicians.

He said: “A long time ago, Syria Street was called the road of gold. It was full of work and, from everywhere around Tripoli, they came. A lot of money and work, the economy was great.

“A long time ago, the Alawites used to live with us. Later on, they moved to Jebel Mohsen, and the politicians made a war between us. With their hands, not our hands. Before we used to live together, we didn’t know what the difference was between Sunni or Alawite; we were like brothers, living safely. The politicians made that war.”

Now, with the economic situation so dire, Mr Ibrahim is clear about which politicians will get the votes of himself and 24 family members and friends — the highest bidder.

He said he had already spoken to some representatives of electoral lists, and was “waiting for the right moment”.

According to another resident of Bab Al Tabbaneh, who asked not to be named, a group of 100 people could get 500 million Lebanese pounds ― 5 million each ― to vote collectively.

Hassan Arour, another local, said he was not surprised by the reports of a low voter turnout by the afternoon.

“A few are waiting for financial support because they need the money. Another part is not voting because of Saad Hariri. Another part are sad because of the boat tragedy,” he said, referring to the sinking of a vessel carrying many Tripoli residents seeking to reach Europe.

“We are suffering now with many problems. No electricity, no water, poverty, unemployment. I think there could be change if the people were against Iran and Hezbollah. If they select the same people, nothing will change.”

One Tripoli resident, who asked not to be named, said he would not vote on any account.

“I think the candidates are about 80 per cent the same. The rest, they are new, true, but they don’t mirror the needs and changes of the normal people like us. They don’t represent us with their ideas and thoughts," he said.

“We want somebody to feel with us, to hurt with us.”

But for Abdel Qadir Sawaf, there was no other choice.

“If you see Lebanon now — no electricity, no economy — we must go and change the political parties, we must do this," he said while sipping a coffee on Azmi Street before heading to a polling station.

‘We tried people before, but we have nothing. I voted before, and I vote again to change the people I voted for before, because they didn’t do anything to help me.”