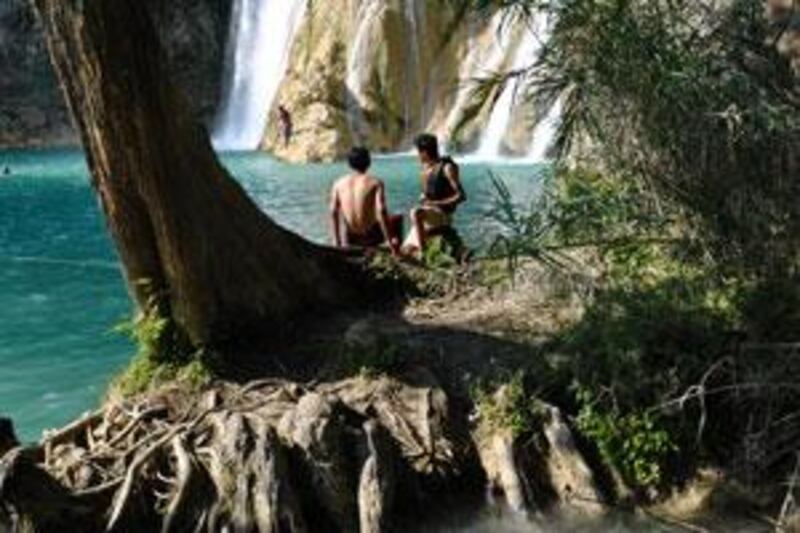

Nestled in Mexico's north-eastern Sierra Madre Mountains roughly 600km north of Mexico City, La Huasteca is a sprawling mass of jungles, caverns, waterfalls and lagoons that creeps into the hilly interior of four different states - and one of the most thrilling, yet little-known, adventures the country possesses. A turquoise-coloured collection of serene waterfalls and lagoons lie at the mercy of the rains and often allow for swimming and snorkelling. The surrounding forests are home to over 2,000 species of plants, and spider monkeys, jaguars and toucans still roam freely in a few areas. Rock formations that look like flat, earthy stones stacked on top of caves dot the terrain. Because of its difficult geography and sparse population, La Huasteca has long been off the beaten path. After driving out of crushing traffic in Mexico City and reaching the mountains some seven hours later, we began a spiralling incline past a few cacti and bushes on rocky, sparsely vegetated land. SUVs whirred up dust clouds as they angled for space on the narrow roads occupied by petrol stations and tiendas. Periodically, a sign emerged with the words la campaña (the countryside) or la fabrica (the factory), and a wide field or a ramshackle factory surfaced. Men with tan, weathered skin in pale-coloured sombreros sat or stood by the road. The area was depressingly desolate until we neared the mountain town of Xilitla. Up and down more slopes, and the scenery underwent a radical makeover. "It's so lush here," said Santiago, one of my friends, as he gazed out of the car window. The sun glowed on the reddish tree leaves and on the intensely thick, green bushes and blonde-coloured wheat. Santiago tuned the radio to local Huastec music, and we were lost in the harp-like sounds and raw, emotion-filled calls. Several indigenous languages are spoken in La Huasteca, including Nahuatl and Huastec, tongues belonging to the Aztecs and a group that split from the Mayans. The descendants of the Aztec Nahuatl and the Huastec still live in these mountains, having mixed and intermarried over the centuries. Though not as well known as their Mayan brethren, the Huastec were celebrated musicians and artisans who created fine, intricate pottery, sculptures and temples. In this hot and humid climate, they wore little clothing, before Spanish Catholica colonialists forced them to cover up when they arrived in the 16th century. The first stop of our trip was Las Pozas, a waterfall attraction just outside sleepy Xilitla. We joined the second half of our group of eight people at a campsite down the road from the park and set up camp amid Mexican kids in tie-dyed headscarves playing rock music from a car radio and a family eating and sleeping in a deluxe van. Lying in a tent that night wondering about the origins of a thousand different noises, I looked forward to the journey ahead into La Huasteca's untamed jungles. Finally, we had arrived. Las Pozas de Xilitla, or The Wells of Xilitla, is near a surrealist-style castle built by Edward James, a British poet. Besides the open-roof house with rickety staircases that stop in mid-air, funky sculptures are sprinkled the over about 30 hectares of natural waterfalls and gardens. Las Pozas was our playground for the day - we climbed up hills and rocks, swam in the pools and took photographs under the falls. I was travelling during Semana Santa - Mexico's Easter holiday break - so half of the obstacle of reaching the higher altitude waterfalls was making it through the crowds, but excepting major holidays, the park is often empty. After a languid afternoon lunch of roasted chicken by the river, we drove through a dark-green abyss to Sótano de las Golandrinas (Pit of the Swallows), a gigantic cavern where we hoped to to witness a little-known wonder. My group woke up at dawn in our camp up the mountain near the town of Aquismón and trekked down half-awake with flashlights to catch the sight of one of the largest open-air pits in the world. The distance from the base of the cave to the upper rim is more than 3,600m. Circles of black swifts, accompanied by splashes of bright green parrots, rose out of the cavern at sunrise, a daily mass exodus that seemed spectacularly effortless. Handlers at the site lowered participants with ropes into the top of the cavern, where the absolute blackness is enormous. I found out that people had parachuted into the hole before. Down the road from Aquismón, the town just outside the Sótano de las Golandrinas, is Nacimiento del Rio Huichihuayán (Birth of the Huichihuayán River). Three kilometres west down a country lane jutting from the main road to reach the village Huichihuayán, a river emerges from the mountains, and the scenery is breathtaking. At this river source, there are large pools of cool, clear water ideal for swimming. They are bordered on one side by a rocky, hollow cave with flowing water that is ripe for exploration, and green trees ideal for climbing or hanging hammocks. From Aquismón it was on to the Cascadas of Tamasopo (The Waterfalls of Tamasopo). Minas Viejas was the exact waterfall we were searching for, since two members of our party had already been there and raved about the stunning, clear waters and secluded location. It was less secluded during this holiday, but the rest held true. It is said the falls run on spring water, and the effect is a clean, aqua-coloured series of both shallow and deep pools. By the time we arrived in the nearby town of El Naranjo that evening at the Hotel San Luis, charming for its large tubs and hot showers, feasting on fresh seafood then going to a pool hall seemed like the only suitable option. We intended to head back home the next morning, but that was before we had breakfast at a restaurant called D'Pico. On our way to a table near the patio, we came across upon the most perfect jungle river scene. Boulders rested on a glistening downwards stretch of water under an intensely bright sun, while dense trees hung overhead, demanding that we stay longer and swim and sunbathe for one last time.

Land of the lush

The great outdoors Nestled in Mexico's north-eastern Sierra Madre Mountains La Huasteca is a sprawling mass of jungles, caverns, waterfalls and lagoons.

Editor's picks

More from The National