Cleaning is a relatively recent human activity and started out of sheer necessity. According to Dr David Holmes, senior psychologist at Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK, our early ancestors only groomed their bodies, but things changed when man began to settle in one place.

"As we abandoned our nomadic ways, we immediately noticed the accumulation of dirt, dust, detritus and even less pleasant human by-products," he explains. "The ability to clean away organic contamination was very important for evolutionary survival in terms of hygiene."

Hygiene still motivates many of us to clean today, but the subject is far richer and more complex. There are many reasons why we clean and keep on cleaning.

Phobia of dirt

Many of us clean because we are anxious about harmful bacteria that can cause disease. Kate Forde, who curated an exhibition entitled Dirt at the Wellcome Collection in London, thinks a phobia of germs is very common today.

"In the late 19th century, there was a growing understanding about germ theory," she explains. "The relationship between bacteria and disease was proved by people like Joseph Lister, who helped people in hospitals to recover by using antiseptic carbolic acid."

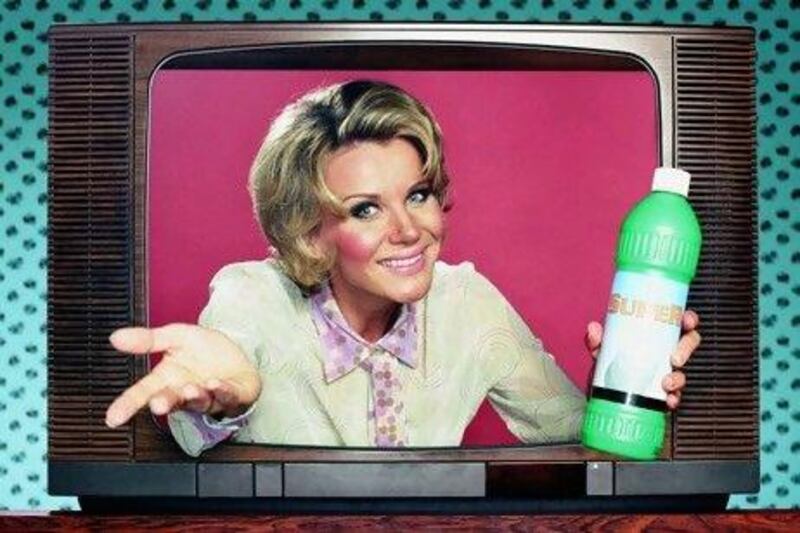

This growing knowledge about how diseases are transmitted influenced soap advertising. "There was a growing language about a 'war' that needs to be 'waged' upon dirt. Dirt was demonised," says Forde. "You still see that sort of language and visual imagery in adverts for cleaning products today."

This powerful message plays on our fear of dirt and suggests that we aren't good people if we don't keep our homes safe from these dangers.

But, as Forde points out, microbial life is far more complex than this simplistic "bacteria are bad" notion. "We're all crawling with microbes and germs - we actually need them," she says. "In fact, some scientific studies suggest that sterile environments don't do our immune systems any good and don't help respiratory problems such as asthma. Overuse of antibacterial products can create an environment that's too clean."

Status

Cleaning has always been a politically and socially charged issue. Generally, throughout history, the physically demanding labour of cleaning has been the responsibility of women or servants. Today, women still do more household chores than men, but we're all concerned with what the neighbours might think.

"The job of cleaning was very time consuming and difficult before the 19th century," says Forde. "People had sooty open fires and candles. It was difficult to get hold of hot water and soap. Poor people couldn't afford to spare the time to keep their homes clean, but the wealthy had an army of servants to help them. Cleanliness was an indication of status."

So, domestic dirt was a sign of poverty and low class and that still influences us today. Most of us give the basin a quick wipe and put out a clean towel before visitors arrive. We're anxious to impress others, and many people look down upon those who live in filthy houses.

A need for order

In her 1966 essay Purity and Danger - An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, the anthropologist Mary Douglas observed: "Dirt is essentially disorder. Eliminating it is not a negative moment, but a positive effort to organise the environment."

She pursued the idea that "dirt is matter out of place" and realised that our relationship with dirt is emotional as well as logical. Forde agrees that humans crave order in a chaotic universe: "There is something pleasing about wiping things clean and starting again," she says. "There's a kind of comfort in cleaning rituals. Inhabiting a well-ordered space is uplifting and gives you pleasure."

Holmes suggests that this desire to make a fresh start is deeply ingrained in our mental makeup: "From primordial times, the fresh new rebirth when bright skies push aside the dark depression of winter boosts our mood and health. Thus, it is hardly surprising that many of us feel a lift in our mood following cleaning," he says. Perhaps this is why spring cleaning is so popular.