In the early 90s, there was a saying among environmental researchers and contract engineers in Abu Dhabi that destroying even one mangrove leaf could land them in jail.

It was a joke, but one that summed up the emirate's deep commitment to mangrove conservation long before climate change and global warming were buzz words.

Australian researcher Ronald Loughland, who moved to Abu Dhabi in 1993 as a 29-year-old PhD student, went on to study the mangroves along the Arabian coast and was astonished by the rulers' passion for protecting the tropical wetland plants amid a time when they were being destroyed globally.

“Abu Dhabi was one of the few places in the world, where the area of mangroves was actually increasing,” Mr Loughland, now 60, told The National.

“That's pretty important and that was because of the plantation programmes.”

He said between 1990 and 2021, the area of mangrove forests in Abu Dhabi increased by around 50 per cent.

Dr Loughland, who has worked as an environmental consultant for the last 30 years, claims to have planted millions of mangroves in Abu Dhabi in the 90s and said environmental conservation was in the DNA of Abu Dhabi rulers.

Sheikh Zayed's legacy

The UAE's Founding Father, the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, and his sons – including the late President, Sheikh Khalifa, and President Sheikh Mohamed – planted the early seeds of Abu Dhabi's ambitious mangrove conservation project.

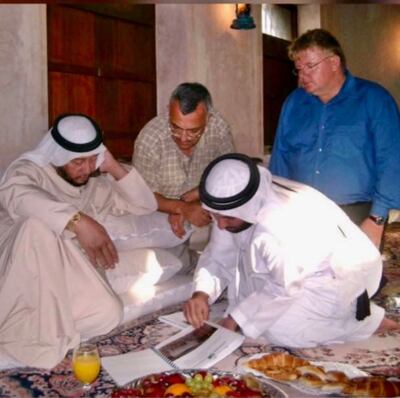

Dr Loughland says he has seen first-hand the keen interest Sheikh Zayed took in ecological conservation.

“I observed Sheikh Zayed and his sons in the field, and they had a contagious enthusiasm for the environment.

“With his sandals off, camel stick in hand, Sheikh Zayed would walk around and give personal instructions to plantation workers with comments such as they were not planting the seeds deep enough,” said Mr Loughland, who is currently consulting for the UAE, splitting his time between Abu Dhabi and Australia.

“His sons would also be with him, listening and following their father's every word. They loved to get the mud between their toes. They really enjoyed it.”

He said Sheikh Zayed valued mangroves as he was a “Bedouin at heart” and a real “man of the earth”.

“He knew the value of trees for shade and for food,” he said.

“And in the old days, when people used to travel on camel, they used [to] go along the coast, and they used to use mangroves for fodder. It is also wood for their cooking fires.”

Lack of climate literacy

Climate change in those days was an unknown concept and little was known about its impact.

“It was considered a future concern. There was also a lot of confusion about what people understood as climate change impacts and mitigation,” said Dr Loughland.

He first came across the impact on climate change when undertaking marine studies that revealed the massive coral bleaching that occurred on the Gulf coast in 1993 due to the rising temperature in seawater.

“That's when I really became a believer in climate change, because I saw it,” he said.

Over 90 per cent of coral reefs in Abu Dhabi and Dubai were lost in the severe coral bleaching reported in 1996 and 1998, according to the Environment Agency Abu Dhabi (EAD).

Dr Loughland was one of a handful of start-up staff at the EAD in 1993 – which was back then based in Sweihan and called the Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency – who conducted the initial surveys on the flora and fauna of Abu Dhabi.

Part of his research also involved looking at satellite imagery and understanding changes in mangrove vegetation.

“This data enabled me to look at all the different pockets where mangroves were growing from 1972 and then every year after that up until the 90s and early 2000s,” he said.

“What occurred was that there was an ongoing increase in mangroves in Abu Dhabi compared to the 1970s. The increase was happening as a result of protection and plantations.

“The irony is that mangroves were actually in serious decline worldwide during this same period, so Abu Dhabi was a real anomaly,” he added.

Travelling with Thesiger

Dr Loughland said he also had the privilege of accompanying legendary British explorer and travel writer, Wilfred Thesiger (also known by his Arabic name, Mubarak Bin London), when he used to visit Abu Dhabi in the 90s on Sheikh Zayed's invitation.

“He used to come as an old man every year to spend the winter in Abu Dhabi because it was too cold in England.

“I spent considerable time with him and would accompany him to banquet dinners and camel races. I used to pick his brains about the environment. What was it like before when he was here in the 1940s? Were there mangroves and where were they? And he would say, 'No, I don't remember seeing very many'.”

Mr Thesiger was known for his extensive trips to the Arabian Peninsula and Africa during the 1940s.

His classic works, such as Arabian Sands and The Marsh Arabs document his experiences and deep understanding of the cultures and landscapes he visited.

He often accompanied Sheikh Zayed on trips and they shared a mutual appreciation for the desert's beauty and the importance of environmental conservation.

Emiratis' love for environment

Dr Loughland said he discovered intriguing differences in behaviour, genetics and species while studying Abu Dhabi's mangroves.

Protecting mangrove genetic diversity is vital for future challenges, as certain genes may offer resistance to climate change, he said.

During his time in the emirate, he said he had helped plant millions of mangroves.

He also established scientific approaches to planting, including using optical hydrological zones on mudflats with the optimal heights determined for best growth.

Seedlings, known locally as “Shitla” in Arabic, were grown extensively in nurseries and later planted in designated coastal areas.

Another part of his contribution included developing new plantation techniques that enabled the conversion of low value saline coastal “Sabkha” into thriving new productive mangrove forests.

Having spent years in the GCC with a hands-on approach to mangrove planting – and developing local talent – Dr Loughland said Abu Dhabi is on the right track with its ambitious plan to plant 100 million mangroves by 2030.

The goal was set to help the emirate to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

Forty-four million of the trees have been planted since 2020, 23 million of them over the last two years covering 9,200 hectares.

It is the Emiratis’ deep love for the environment, that makes all the difference, said Dr Loughland.

“And the most wonderful thing is they have kept it going, this passion. The young Sheikhs, the third-generation rulers have also nurtured this love for nature. They are switched on when it comes to environment.”