As the global appetite for energy grows, the way it is produced, distributed and consumed is undergoing a profound transformation.

As educators, we need to prepare our students to confidently enter the job market and participate in finding solutions for tomorrow's energy challenges. That may require a transformation equally profound in the way we educate them.

Today, fossil fuel or nuclear power plants centralise the production of electricity, which is distributed to consumers through the power grid.

But they are slowly giving way to renewable energy technologies that are decentralising and democratising power production.

Smaller solar and wind farms are springing up everywhere. Today, basically anyone can become an electricity producer and feed excess power into the grid.

Technological developments in data sensing, computation, and wireless communication are further fueling this transformation.

By bringing us smart household appliances, smart buildings, and ultimately smart cities, they promise to provide the tools to manage our electricity consumption more efficiently.

While these changes are making our relationship with energy more sustainable, they are also making it more complicated.

For example, it is one thing to control the production of electricity in a small number of conventional power plants.

But when each home can either be an electricity consumer or a provider, the level of sophistication needed to guarantee efficient distribution of the power increases drastically.

The individual pieces needed to address many of these challenges exist, but are often spread out in different fields of science. So how can we bring them together so that they can combine to form innovative solutions that would improve the way we manage energy?

Fostering this kind of innovation requires revolutionising the way we educate our students. We need a new breed of graduates that thrives in these uncharted waters. While still rooted in one scientific discipline, they must be proficient in several others.

For that, we need to break down the barriers between the traditionally separate fields of physics, architecture, civil engineering, micro-technology, mechanical, environmental and electrical engineering.

At the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) Middle East, we have designed a master's programme around this challenge. At its core lies a mission, not a scientific discipline, described by its title: energy management and sustainability. The programme centres around four research labs, associated with EPFL Middle East, but located in Lausanne, in Switzerland.

In each, an international group of students from a wide range of backgrounds are brought together around a common challenge, divided into individual but interconnected sub-projects.

As they interact, the students share thoughts and ideas and exchange the knowledge and perspectives they brought from their undergraduate degrees.

In doing so, they acquire the vocabulary used by their peers and learn their points of view.

The need for graduates with an interdisciplinary education does not mean traditional fields are becoming obsolete.

On the contrary, as both the challenges we face and the solutions we develop to address them become more complex, there is no way to do without specialists.

But let's not forget how melting barriers between computer science and telecommunications paved the way for the mobile technologies we already often take for granted today.

Just imagine what the future could look like if we follow a similar path and break down the walls that separate the many fields of science that deal with energy.

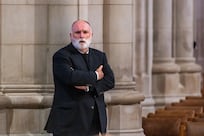

Prof Maher Kayal is director of the electronics laboratory at EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland, and director of the EPFL Middle East masters programme in energy management and sustainability