SpaceX postponed on Wednesday what would have been its first commercial launch with the Falcon Heavy rocket, citing strong wind in the upper atmosphere.

The next window for the mission is Thursday, Florida time, the company said.

On the same day human kind saw a black hole for the first time, Elon Musk’s SpaceX had been preparing to launch Falcon Heavy - its massive, heavy-lift rocket - for the first paying customer, more than a year after a demonstration mission in February 2018.

Last year’s initial Falcon Heavy launch became a spectacle thanks in part to its test payload consisting of Musk’s cherry-red Tesla Roadster with a mannequin passenger, dubbed Starman, sitting in the driver’s seat.

This time SpaceX will be carrying a payload for Saudi Arabia's Arabsat, a satellite services provider. The Arabsat satellite will deploy about 34 minutes after launch, according to Bloomberg.

If the weather holds on Thursday and there are no technical issues, Falcon Heavy will rumble aloft from Nasa's Kennedy Space Centre. It may well be auspicious that should it take place, llift-off will be just over a day after astronomers revealed they had taken the first-ever image of a black hole.

Lurking at the centre of a distant galaxy named M87, the object has a mass over 6 billion times that of the sun and a gravitational field so intense not even light can escape its clutches.

Back on Earth, scores of SpaceX fans and tourists are still camped at the Florida Space Coast for the Falcon launch event, which will be broadcast live on the SpaceX website. The Falcon Heavy has three boosters with 27 Merlin liquid-propellant engines in total, giving it more than 5 million pounds of thrust - the most for a launch since the Saturn V rocket last used for Apollo moon missions in early 1970s.

For SpaceX, the introduction of the large and reusable Falcon Heavy into its launch business gives the company the ability to bid on heavier payloads than it can with the smaller Falcon 9 rocket, opening up the market for big commercial satellites launches and national security missions. A standard Falcon Heavy launch costs $90 million, according to the company’s website, compared to $62m for the Falcon 9.

SpaceX has several paying customers committed to flying on Falcon Heavy, including Inmarsat, Viastat and Arabsat, according to its launch manifest. The US Air Force also chose Falcon Heavy for its STP-2, or Space Test Program 2 mission.

Following the launch, SpaceX will attempt to simultaneously return the two side boosters to landing pads and land the center core on a drone ship. Last year, SpaceX recovered two Falcon Heavy boosters on land but narrowly missed landing the third on a drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean.

SpaceX set a company record last year with 21 launches for customers. This year the big focus is on human flight: SpaceX has a contract with Nasa to send US astronauts to the International Space Station as part of what’s known as the Commercial Crew programme.

In early March, SpaceX pulled off a key test by sending an unmanned Crew Dragon spacecraft to the ISS, then recovering it after a flawless splashdown. Proving that SpaceX can safely fly humans is key to Mr Musk's ambitions for space tourism and creating a human colony on Mars.

The planned Space X launch comes after Virgin Galactic’s first test passenger received her commercial astronaut wings from the US aviation regulator on Tuesday after flying on the company’s rocket plane to evaluate the customer experience in February.

Virgin Galactic’s chief astronaut instructor, Beth Moses, who is a former Nasa engineer, became the first woman to fly to space on a commercial vehicle when she joined pilots David Mackay and Mike Masucci on SpaceShipTwo VSS Unity.

The wings were presented to the three-person crew at the 35th Space Symposium in Colorado by the Federal Aviation Administration's associate administrator for commercial space, Wayne Monteith. “Commercial human space flight is now a reality,” he said.

The February test flight nudged Richard Branson’s space travel company closer to delivering suborbital flights for the more than 600 people who have paid Virgin Galactic about $80m in deposits, according to Reuters. Mr Branson has said he hopes to be the first passenger on a commercial flight in 2019.

The 90-minute flight, during which passengers will be able to experience a few minutes of weightlessness and see the Earth’s curvature, costs $250,000 – a price that the company said will increase before it falls.

Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin has launched its New Shepard rocket to space, but its trips have not yet carried humans. SpaceX last year named Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa as its first passenger on a voyage around the moon, tentatively scheduled for 2023.

Ms Moses, who as a Nasa engineer worked on the assembly of the International Space Station, is designing a three-day training program for Virgin Galactic’s future space tourists.

“I gleaned a lot of firsthand information that we can roll into the design and then also into the training,” she said on her return to earth in Mojave, California, in February.

A few days prior to Virgin's wings were presentataion, Amazon on Thursday confirmed it is working on a project to deploy a network of satellites for high-speed internet service in underserved parts of the world.

Project Kuiper was first reported by tech news website GeekWire, which cited US regulatory filings disclosing the satellite project that could cost billions of dollars to complete.

"Project Kuiper is a new initiative to launch a constellation of low earth orbit satellites that will provide low-latency, high-speed broadband connectivity to unserved and underserved communities around the world," Amazon said in response to an AFP inquiry.

"This is a long-term project that envisions serving tens of millions of people who lack basic access to broadband internet."

The filings described a plan to put 3,236 satellites in low orbit at altitudes ranging from 367 miles (590 kilometers) to 391 mile (630-kilometer), according to GeekWire.

The frontier of space is internationally agreed to be 100km above Earth, known as the Karman Line.

The Seattle-based online powerhouse was looking to partner with like-minded companies on the effort. There was no indication that Project Kuiper thus far involved Blue Origin, the rocket company owned by Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos, which blasted off the 10th test flight of its New Shepard rocket early this year. The rocket, like the Falcon, is resuable and lands back on Earth after a flight.

More test flights lie ahead, but the first flights with passengers on board could start by late 2019.

It's not just the established heavyweights of commerical rocket sector who aim to benefit from the new space race.

Relativity Space, the company founded by Tim Ellis in December 2015 with the vision of launching 3D-printed rockets, has grown from 14 to 80 employees in one year and will recruit another 40 this year.

Mr Ellis, 28, has lured several industry veterans, including from SpaceX.

Relativity Space has raised $45 million so far, Canadian satellite operator Telesat has entrusted it with the launch of part of its future 5G satellite constellation and the US military has given it a launch pad at Cape Canaveral.

And Mr Ellis, who six years ago was still studying for his masters in aerospace engineering at the University of Southern California, now sits on the White House's National Space Council along with former astronauts and the heads of the largest American aerospace groups.

"I'm the youngest person by more than 20 years, and we're the only venture capital backed start-up," Mr Ellis told AFP during the 35th annual Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, a major annual event for the space industry that will welcome 15,000 participants from 40 countries.

Dozens of start-ups have announced plans in recent years to build small and medium rockets to launch small satellites. Many will probably fail before having made their first rocket, but that's the game, Mr Ellis explained.

"The notion in Silicon Valley is you're going to take tons of big bets, where lots of them will totally lose money. But the ones that succeed will pay for all of the losers - and in a huge outcome, if it's the next Google or the next SpaceX," he said.

Relativity Space, which like SpaceX is based in Los Angeles, has so far printed nine rocket engines and three second stages for its rocket model, called Terran 1, whose first test flight is scheduled for the end of 2020.

Only the electronics are not 3D-printed.

"It's much cheaper, because of the labor reduction in the automation with 3D-printing," said Mr Ellis, who will charge $10 million for a launch, at least at first.

"Also, it's more flexible," he said: eventually, Relativity Space will adapt the size of the fairings of the rockets to the requirements of individual customers, depending on the size of their satellite.

Speed is the other advantage: "Our target is to get from raw material to flight in 60 days," Mr Ellis said.

If Relativity Space succeeds in this feat - which it has not yet demonstrated - it would revolutionise the launch industry. Today, a satellite operator can wait for years before having a place in the large rockets of Arianespace or SpaceX.

The Terran 1 will be 10 times smaller the SpaceXFalcon 9, able to place a 1,250 kilogram (2,755 pounds) payload into very low orbit (185 kilometres above the Earth's surface).

This could be suitable for a constellation of small satellites for telecommunications or imaging the Earth, but also for one of the largest customers in space: the US military.

This is another reason for the young executive's arrival in Colorado Springs: meeting senior Pentagon officials.

While small-fry make big waves, established aerospace veterans show that bad times can befall any company. Boeing has just delayed from April to August its test flight for its Starliner capsule, intended to carry American astronauts to the International Space Station.

Nasa blamed the delay on "limited launch opportunities" in April and May from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

It noted that the August launch target is a "working date and to be confirmed."

The Starliner spacecraft, which is in the final phase of ground tests, is set to be launched into space atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket.

If the unmanned test goes well, the capsule's next flight will have three astronauts aboard - Nasa's Nicole Mann and Mike Fincke, along with Chris Ferguson of Boeing.

Ultimately, Starliner will be one of two American vehicles used to carry Nasa astronauts to the ISS - the other is SpaceX's Dragon capsule.

Elsewhere, The National this week reported on US firms Orion Span's project to launch an orbiting luxury space hotel by 2022. And even at $9.5 milion for 12 nights aboard the Aurora Station, the founder and CEO Frank Bunger says 26 people have already paid the 80,000 deposit to make the trip.

Of course, orbital space is just the beginning and some firms have much grander, if possibly less likely, ambitions.

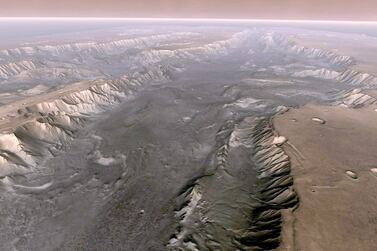

Georgia is immensely proud of its ancient grape-growing tradition, claiming to have been the first nation to make grape-based beverages. Now it wants to be the first to grow grapes on Mars.

Nestling between the Great Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea, Georgia has a mild climate that is perfect for vineyards and has developed a thriving tourism industry around viticulture.

Now Nikoloz Doborjginidze has co-founded a project to develop grape varieties that can be grown on Mars.

"Georgians were first wine makers on Earth and now we hope to pioneer viticulture on the planet next door," he told AFP.

After Nasa called for the public to contribute ideas for a "sustained human presence" on the Red Planet, a group of Georgian researchers and entrepreneurs got together to propel the country's winemaking onto an interplanetary level.

Their project is called IX Millennium - a reference to Georgia's long history of wine-making.

Since archaeologists found traces of wine residue in ancient clay vessels, the country has boasted that it has been making wine for 8,000 years -- longer than any other nation.

IX Millennium is managed by a consortium set up by the Georgian Space Research Agency, Tbilisi's Business and Technology University, the National Museum and a company called Space Farms.

While it might seem like the stuff of science fiction, the idea of humans quaffing wine on the fourth planet from the Sun is coming closer to reality.

Nasa hopes to launch a manned mission to Mars within 25 yearsand is researching growing potatoes on the Red Planet at a facility in Peru.

In Georgia, MsTarasashvili and her colleagues are also testing the skins of Georgia's 525 indigenous grape varieties to establish which are most resistant to the high levels of ultra-violet radiation hitting the Martian surface.

Preliminary results showed that pale-skinned Rkatsiteli grapes best endures ultra-violet rays.

"In the distant future, Martian colonists will be able to grow plants directly in Martian soil," said Tusia Garibashvili, founder of Space Farms.

Still, as Nino Enukidze, the Dean at the Business and Technology University said, there is a practical element to such lofty ambitions that may well come in handy closer to home

"Martian dreams aside, our experiments are providing information that is vital as humanity confronts a multitude of environmental challenges."