It took the death of a South African mine worker, who killed himself by drinking ant poison, to finally put an end to the tragedy.

The suicide of Marius Ferreira, who had been reduced to starvation because his employer had stopped paying salaries to its workers a year ago, has also renewed calls to revise policies intended to benefit black Africans, but which has frequently enriched only a few.

Mr Ferreira had been a worker at a mine owned by Aurora Empowerment Systems, led by a clique of business figures drawn from some of South Africa's most powerful families.

Among them are Zondwa Mandela, Nelson Mandela's grandson, who is Aurora's managing director, and Khulubuse Zuma, the South African president Jacob Zuma's nephew, and the company chairman.

The saga began when Aurora won a bid to take over a liquidated mining company, which owned two mines on the outskirts of Johannesburg. Aurora's bid of 600 million rand (Dh319.3m) for the mines was twice as high as bids put in by experienced mining companies also vying for the assets.

As it turned out, Aurora had neither the money, nor mining expertise to run the operations. Its promised funding from, in turn, Malaysian, Swiss and Chinese backers, never materialised. As each investor pulled out, government-appointed liquidators extended Aurora's tenure over the mines, as they sought fresh capital.

In the meantime, Aurora stopped paying workers and maintenance costs for the mineshafts. And as operations came to a halt, equipment, including machinery and vital water pumps to keep the mines from flooding with groundwater, was removed and sold for scrap. The flooding has also threatened nearby mines operated by other companies, forcing some to cut back on underground operations.

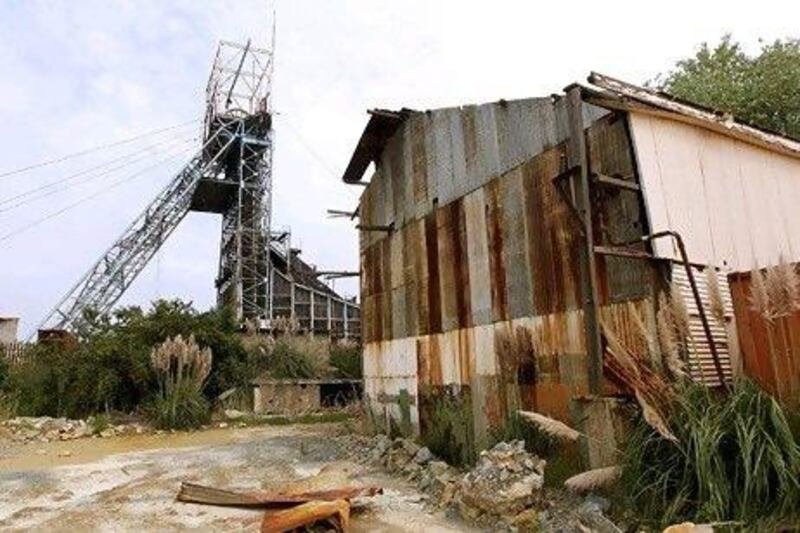

A parliamentary briefing on the affair last month was told that once-productive mine shafts were now open to the air because their steel headgear, used to bring men and ore in and out of the pits, had been removed. This month a man plunged 400 metres to his death down one of the open shafts.

Gangs of illegal miners, taking advantage of the lack of management, have moved in and forage for gold in the increasingly unsafe pits. Last August four illegal prospectors were killed in a shootout deep underground with security guards. News reports suggest more bodies lie undiscovered at the bottom of abandoned mine pits, victims of accidents or conflicts between rival gangs of pirate miners.

Finally last month, following the parliamentary hearings and the deluge of publicity they created, Aurora was kicked off the mines.

"It's mind-boggling," said Gideon du Plessis, the deputy secretary general of the Solidarity union. "You don't expect things like this to happen. I don't want to use strong words like 'failing state', but there are signs there."

The union said some of the mine shafts that Aurora had run will probably never return to full productivity. The water-pumping equipment alone, which was also removed and sold for scrap, will cost 50m rand to replace, Mr du Plessis said. Some shafts have already flooded and cannot be safely reopened.

The unions now want the directors of Aurora to be permanently barred from doing business in the mining industry, and for a full criminal investigation to take place.

The public outcry over the Aurora scandal has led the government to impose a six-month moratorium on applications for new prospecting licences. It has also promised to review laws that critics say give ministry officials too much discretion and personal leeway in granting these licences.

The ruling African National Congress is under pressure to bring black people into a white-dominated economy. It has set a target of 26 per cent ownership of mines in the hands of black people by 2014. As a result, mining companies such as BHP Billiton, Anglo American and a host of others have scrambled to bring black people into their boardrooms and as shareholders.

The rush to fill the target has also meant prospecting licences have been granted to entities such as Aurora that had no previous deep level mining experience.

For the communities that depended on the Aurora mines for their living, however, these policies have delivered only hardship. Mr du Plessis said the mine workers, their families as well as the towns that were sustained by mining operations, will take years to recover.

"Aurora is not only responsible for the massive social crisis which impoverished more than 40,000 people, but they also stripped the mining asset of all value and caused South Africa's image as an investment possibility immeasurable damage," he said.