Peter Busby's buildings often look as if they came back from the future. A rapid-transport station he designed in his hometown of Vancouver, Canada, looks like a glowing white cocoon suspended in space. The head office he reworked for the local telephone company, Telus, has become a Japanese-minimalist box of opaque glass. The 90-storey tower he is crafting for Dubai International Finance Centre has windmills suspended in the centre of the structure.

But when Busby was asked to bring his architectural skills to the team creating Plan Abu Dhabi 2030, the scheme for the city's development, he didn't only look forward for ideas. He went back in time. "We visited some traditional cities, went to the heart of Riyadh and Jeddah. You can learn a lot from those," he said, during a call from Tanzania, the latest stop in his increasingly international practice.

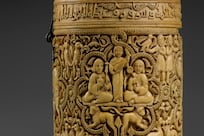

In Al-Balad, the old quarter of Jeddah, he saw the traditional architecture that combines thick walls, to help keep interiors cool, with decorative elements like elaborately carved wood screens over windows, curved doorways, and thick wooden crossbeams that make buildings look like layered birthday cakes. In Old Riyadh he saw adobe buildings, walled courtyards and covered streets. He was impressed with how effective the old cities were at creating shade and cool streets.

Some traditions, like building with adobe or using wooden crossbeams, couldn't be adapted to modern structures and cities. But what Busby saw prompted him to bring some centuries-old practices to the current plans for both the capital and Al Ain. This means that wind towers, the traditional form of cooling that used to be prevalent in Arab cities, will reappear, as will the wooden screens or mushrabiya. So will the pattern of orienting streets north-south and making them narrow, to reduce glare and create the maximum amount of shade. He will also employ the concept of using pools of water, where evaporation can cool, humidify and create small breezes in hot, dry air.

Those very old ideas have been blended in the Abu Dhabi plans with the pioneering techniques Busby has become famous for in Canada and around the world, as he strives to make buildings and design friendlier to the planet. So, one day, two decades from now, when you go into a house or office that gets its energy from solar panels on the roof and its cooling from a tower that captures air from above and funnels it down, or when you are happy to abandon your car for walking and public transport because the streets are shaded with trellises and the metro stations have been strategically located, it will be because Peter Busby helped make that possible.

You may not see an actual Busby design - at this point, he hasn't been asked to do any specific buildings - but he will be all around you. So who is this man who will have such a pervasive presence in the new Abu Dhabi? Busby, who turned 56 this autumn, did not plan to be an architect. He studied philosophy in university, but he supported himself and his wife Catherine, by working on construction jobs. He found that he liked the practicality of building.

He also found himself spending more and more time in the offices of the architects whose projects he was working on. When he finished his degree he knew what he wanted to do next. "I couldn't stay in philosophy because it was too sedentary. It didn't involve enough action or the ability to put rubber to the road," he said during an interview at the small island house near Vancouver that is his refuge from a life lived on aeroplanes. (This past month: Venice, Tanzania, Abu Dhabi, Bahrain.)

It was a rare sight, that day, to see him not wearing a suit. Instead, Busby, who has the look of a particularly intense accountant, is in shorts and a golf shirt, talking about why having a hammer in his hand and a tool belt around his waist still makes him happier than anything else. Even more than philosophy. "But I obviously came out of that with some ethical and moral positions. I brought that value set to architecture."

He graduated from architecture school in Vancouver in 1977 and went to work in London and then Hong Kong for Norman Foster's high-powered architecture practice. From the beginning, Busby was interested in designing green buildings. When he moved back to Vancouver and set up his own practice in 1984, one of his first major projects was a housing development on Bowen Island, near Vancouver. He had read Ian McHarg's groundbreaking book Design with Nature. Published in 1969, it was one of the first books that talked about designing developments in a way that would reduce the impact on the environment.

Using its ideas, he created a subdivision plan for the island that would save three-quarters of the forest cover, where the sewage would be treated on-site, where the water would come from local sources, and where every house would have a sense of privacy and a view. Busby has done one of almost everything in Vancouver: offices, apartment buildings, a city hall, a marina, two transit stations, a community centre and a materials-testing facility. He is now at work on two hospitals, a public-garden complex, and a low-cost housing development in the most rundown part of the city.

Elsewhere, he has designed a post-secondary institution that incorporated styles from a local native Indian community, a marine park in Italy, and North America's greenest residential development, called Dockside Green, in Victoria, Canada. Along the way, he has become one of the country's leading public campaigners for sustainability and a pioneer in incorporating increasingly sophisticated mechanisms for saving energy and recycling into his buildings. "He was one of the very first in Vancouver who started to put green into the mainstream buildings," says Mark Holland, a Canadian sustainability consultant.

Busby even pushed the idea of making buildings more environmentally friendly for customers who had no interest in the concept. "What we have done is some great green buildings and not told our private clients about it," says Blair McCarry, an engineer who has worked closely with Busby on many of his projects. "On the prairies, if you talked green, they thought you were a tree-hugger. Save the planet, polar bears - that doesn't go anywhere there."

But Busby would talk to them about how an energy-efficient project could lower their long-term costs - and that would sell them. Driving one of the country's most ambitious environmental agendas is not easy. A founder of the Canada Green Business Council, Busby dedicates 20 per cent of his time to advocacy work, a commitment that takes its toll. And, to get what he wants, he doesn't suffer fools gladly. In interviews he is affable, although always driving his sentences through as though there will never be quite enough time to tell you everything you need to know about sustainable architecture. At work he is well-known for the sharp edge of his tongue, quick to say, "Is that the best you can do? Isn't there a better solution?" He challenges people he's with to do more, something McCarry says diplomatically makes for a "bit of tension".

But that edginess and overbooked life is reaping its reward. Busby, who was awarded the Order of Canada three years ago for his campaigning, has the satisfaction of seeing people around the world getting interested in environmental city design and buildings. Like Abu Dhabi. Busby got pulled into the Abu Dhabi team through the man who has been at the centre of it since the beginning, Larry Beasley. Beasley, the former co-director of planning for Vancouver, was recruited in June 2006 to help Abu Dhabi plan its urban future. He quickly brought in others to complement his expertise, including Busby, who could talk to the planners about the architectural requirements for their ideas in all four parts of the emirate's total redesign: the existing city, the new capital city, Al Ain, and the western region.

That has meant doing everything from helping Abu Dhabi come up with a ratings system for assessing a building's sustainability to planning a public transport plan and figuring out which parts of the local area are best suited for which green-design technologies. Solar panels are an obvious fit; so is anything that can save water. His one observation about trying to build ecologically in Abu Dhabi is that almost nothing, except for concrete, is produced locally because of the environmental conditions. But the photovoltaics (PV) for solar panels - something he has pushed for extensive use of - are made from silicon. "That's made from sand and there's lots of that here."

The government has grasped the opportunity; in May, Masdar, a subsidiary of the government-owned Mubadala Development Company, announced a $2 billion (Dh7.3 bn) project to build PV factories here and in Germany, which leads the world in that technology. Along the way, Busby has also become the co-ordinating architect for the new Capital District. Local architects go to Busby to get his thoughts and suggestions for their buildings and how they would fit with the capital's design guidelines.

Those guidelines, aimed to create a look and feel for the capital reminiscent of the grandeur of Washington DC or Canberra, Australia, specify everything from the height of buildings (low) to the materials (stone, in the cream-coloured palette that is typical of Arab cities) to the look (solid, with punched-in windows, rather than glass and aluminium towers that would be heat traps). While Busby still likes the architectural side of his life, the chance to plan a whole city and, potentially, to create a new way of life for the metropolises of the Gulf - a region where villages became cities overnight, rather than growing organically - is the most rewarding part of the job.

"The key thing for me is that, in that part of the world, there are no pedestrian cities. We think it's feasible to make it a pleasant experience to walk around if it's properly shaded. If we can create a pedestrian-oriented city in the desert, that would be great."