Some of the world's most powerful movers and shakers convened in New York City this week to share findings on how to best educate and financially empower more women in developing economies.

While few of them agreed on taking the same course of action, one theme seemed to emerge among leaders from the public, private and non-profit sectors who attended the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) annual meeting to address the world's most pressing social problems: it is time to provide females with support on a continuum that starts in early childhood and stems well into adulthood.

After all, some argued, investing in women does not just make fiscal sense, but it is also an economic imperative in this uncertain global economy.

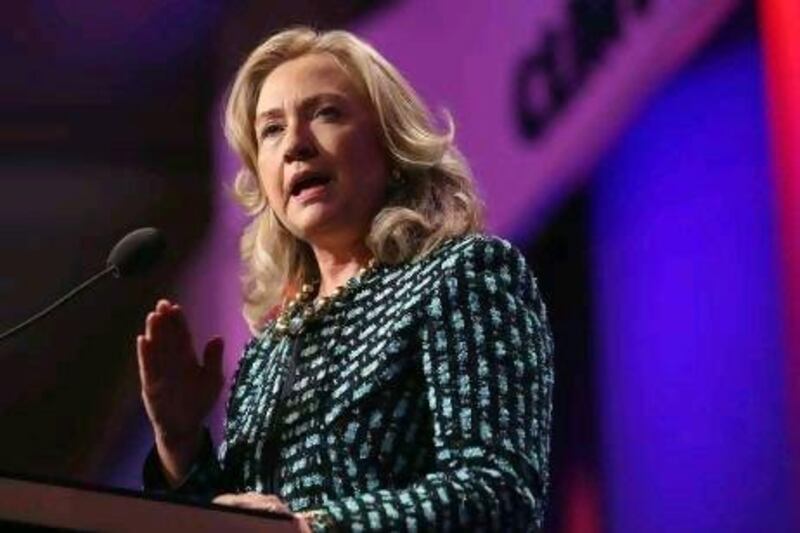

"A growing body of evidence proves what is intuitive: when more women enter the workforce it spurs innovation, increases productivity and grows economies," said Hillary Clinton, the US Secretary of State.

"Families then have more money to spend, businesses can expand their consumer base and increase their profits. In short, everyone benefits."

Put another way, as US President Barack Obama did, "by every benchmark, nations that educate their women end up being more successful."

But getting to the point where women can actually enter the workforce en masse, especially in developing markets such as the Middle East, Africa and India, first requires looking at development as well as education in early childhood.

The first 1,000 days of a child's life are the most crucial for healthy growth, some experts said, although they also warned that many girls lack the nutrition they need and end up stunted later in life - both literally, in height and health, as well as economically.

"When stunted children enter the workforce as adults, their earning capacity is estimated 22 per cent less than their peers," said Geeta Rao Gupta, the deputy executive director for Unicef, the organisation that advocates for children.

Other research discussed at CGI has found that boosting nutrition education among mothers and properly developing the brains of young girls and boys in their first few years of life can boost a country's GDP by up to 3 per cent.

"This investment in the early years is absolutely the best investment we can make," said Carolyn Miles, the president and chief executive of Save the Children, another advocacy group for kids.

Creating adequate early year school programmes is also crucial, as research has shown that significantly more girls enrol in primary school than those who do not, even when they have spent just one year in pre-school. More than 35 million girls are not attending primary school in developing economies, according to the World Bank.

Yet lowering this number requires taking a customised approach that will engage girls throughout primary school, then into secondary school and beyond. This would require local content and skills training so women could more easily garner employment or launch a venture of their own, experts said.

Take Yemen, for example. In the absence of support from government funds, some philanthropic businessmen stepped in to build schools exclusively for girls who had otherwise stayed away because they did not want to mix with boys.

Private buses have also been brought in to encourage more Arab girls to attend classes in an environment that feels safer to both them and their parents, said Salma Samar Damluji, the chief architect at Daw'an Mud Brick Architecture Foundation, which works in Yemen.

In other developing countries, where access to school for young females is still scarce, many end up staying with their mothers in marketplaces. Such is the case in Malawi, Africa. "Most of those children, when they grow up, are the ones that end up in the market anyway, because they'll never go to school," said Joyce Banda, the president of Malawi.

While this kind of scenario does not always lead to a poor financial outcome, many young women who start working in a marketplace lack the money-management skills to scale up their business. Access to capital continues to be a chronic problem for these women, although some financial firms have recently made moves to help foster female entrepreneurship and boost financial literacy.

At CGI, heads of both the Inter-American Development Bank and Goldman Sachs spoke about programmes that have helped women to grow their enterprises from small to medium. The former has provided microcredit through its bank to women in Latin America, while the latter runs a "10,000 women" programme that invests in business education for women in emerging markets.

A new initiative announced at this year's CGI will see a woman-owned radio station in the West Bank train and hire community reporters and students in radio reporting or broadcasting to advance positive representations of Palestinian women in media.

Other programmes aimed at females in developing or emerging economies that were formally launched this week included DreamBuilder, which provides online business skills training to women in certain mining communities of Peru and Chile, as well as a commitment from the Georges Malaika Foundation to expand educational access to 340 young girls in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Even so, some CGI attendees said more vocational and technical training was needed in emerging markets, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa, where a wide gap still exists between what the market demands and the skills being taught to high school and university students.

"If there's one thing we need to focus on, it's redesigning our educational systems," said Queen Rania Al Abdullah of Jordan. "At the moment, we're teaching yesterday's skills."