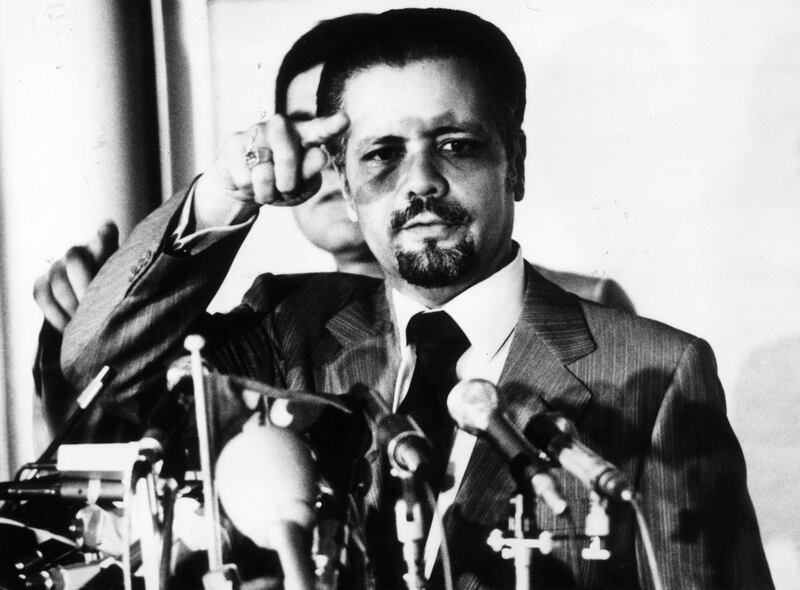

The death of Saudi Arabia's former oil minister Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani removes from the stage one of the most consequential figures, other than heads of government, in the post-war world.

People have written about his personality and life. But it is important also to understand his achievements – in front of the camera at Opec press conferences and, more quietly, in Saudi Arabia – that left an enduring impression on the global energy business and the economy.

The sheer length of Sheikh Yamani’s tenure was remarkable: 25 years in the top job through the most turbulent times in the oil market’s history.

By an odd coincidence, he was aged 90 when he died – the same age as close associate and former Opec secretary general Fadhil Chalabi of Iraq who died in 2019 and Venezuela’s Alirio Parra, one of the key figures at the formation of the bloc in 1960, who died in 2018.

These men and their colleagues played a pivotal role at a time when control of the global oil business passed from the “Seven Sisters” – large western oil companies – to resource-holding countries.

The 1960s were a difficult time for oil producers, characterised by political volatility, low prices and a scramble for market share as global oil demand grew quickly while potential output rose at an even faster pace.

Sheikh Yamani replaced Abdullah Tariki, Saudi Arabia’s first oil minister, in 1962. Tariki, the vocal and confrontational “Red Sheikh”, had been a guiding spirit behind the formation of Opec after western oil companies decided to cut the official “posted prices”, which were used to determine their tax liability, to 1949 levels.

His successor negotiated hard in private to raise the kingdom’s share of taxes. However, both men recognised then that they could not push too hard and were wary after the US-inspired overthrow of Iran’s Mohammad Mossadeq in 1953 after he nationalised the country’s oil sector.

In 1962, the kingdom’s oil production – at 1.64 million barrels per day – was less than Kuwait’s and a fifth of US production.

By 1976, it had overtaken the US as it churned out 8.58 million bpd, and only the Soviet Union produced more.

Not even America’s shale boom over the past decade compares in speed and scope with this expansion.

Along with the peak of American oil output in 1970, Middle East expansion passed the baton to the Opec states. Iran and Libya kicked off a round of price rises in 1971, which Saudi Arabia was glad to benefit from.

The changing market dynamic and political developments brought Sheikh Yamani to the centre of global affairs. The attempted oil embargo by Arab states around the 1967 Arab-Israeli war was foiled due to ample spare production capacity elsewhere. By contrast, the decision of King Faisal and others to launch a boycott after the October War of 1973 triggered panic among buyers and prices almost doubled overnight.

Sheikh Yamani, along with Chalabi and a few others, was far-sighted in perceiving the dangers of extremely high prices. He feared that making oil uncompetitive would damage the world economy and encourage competitors – exactly the problems another Saudi oil minister, Ali Al Naimi, would confront in the 21st century. He argued for moderate price rises.

However unpleasant the consequences for the industrialised countries, the accessible and charming Sheikh Yamani was a welcome change from the self-serving preachy attitude of the Shah of Iran or the hostile rhetoric of Colonel Muammar Qaddafi.

While Henry Kissinger inspired the formation of the International Energy Agency in 1974 as an explicit counterweight to Opec and mused in threatening fashion at press conferences about American “countermeasures” to the crisis, constructive dialogue was essential.

Opec’s records from this period are a fascinating testament to Sheikh Yamani’s diplomatic skills and his ability to find tactics to steer the fractious Opec gatherings through uncharted waters while focusing on long-term strategy in conditions wholly alien to all oil-market participants.

In the early 1980s, his warnings came true. Prices were high after the 1979 Iranian revolution, resulting in a slump in demand. Sheikh Yamani faced an impossible task as the kingdom attempted to defend prices alone.

In 1986, he made the right decision to raise output and accept a price cut but this led to his own exit from the role he had done so much to define: the central banker of global oil.

Yet too often, Sheikh Yamani’s career is seen only through the prism of Opec. That is understandable for western audiences, given his visibility as the most prominent interlocutor for the oil producers during the energy crises.

But his domestic role was also incredibly important, perhaps even more enduring. He laid the groundwork in the 1970s for large-scale refining and petrochemical ventures in the kingdom, including the 1976 formation of Saudi Basic Industries Corporation, or Sabic, and measures to diversify exports and constructively use associated gas from oil production, ending the flaring that still blights Iraq and Iran.

He also managed the state’s gradual acquisition of Aramco, formerly a consortium of the four large American oil companies, acquiring 25 per cent in 1973, another 35 per cent in 1974 and the remainder in 1976. Operations were eventually handed over by 1988.

This steady process avoided the chaotic nationalisation of post-revolutionary Iran, the hostile takeover in Qaddafi’s Libya or the overtly nationalistic expulsion in Iraq.

The renamed Saudi Aramco retained its technical skills, management structures and apolitical approach, vital for the efficient management of the world’s largest oil reservoirs and for the credibility of its eventual initial public offering in 2019.

The oil world is barely recognisable from 1962 but the dilemmas of 1986 seem familiar. Sheikh Yamani’s tenure spanned that transformation. His modern counterparts in the big oil producers can learn much from his approach as they face the next great shift in global energy.

Robin Mills is chief executive of Qamar Energy and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis