SEOUL // Call them "newly emerged" or "near emerged" or just plain "emerging" but newcomers are changing the architecture of global finance.

As host of next week's summit of world leaders from the Group of 20 (G20) leading and emerging economies, South Korea is playing the role of go-between on contentious issues on behalf of up-and-coming economies from Asia to Latin America. Suddenly, those left out of the outmoded G7 have new power and influence.

The question is, however, will the gathering of so many leaders with divergent views produce substantive results?

"We will have to balance the international system," Paul Volcker, the chairman of the US President Barack Obama's economic recovery board, said on Friday. "I am sure that will be the prime area of discussion when the G20 gets together. The challenge will be to move beyond the talk" and "go away from the meeting with a real consensus".

For South Korea, the first ever non-G7 country to host a G20 get-together, the pressure is overwhelming. The government is asking schoolchildren and office workers to help clean up the streets, while 50,000 policemen are guarding the venue of the summit in the vast Convention and Exposition Centre, keeping would-be protesters at least 3km away.

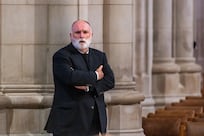

All that, however, only adds to the excitement of such observers as Chang Yu-sang, a visiting professor at the influential Korea Development Institute, as he talks about what G20 means to him and to Korea.

"This is a big deal," he says. "It's historic. Korea never had this kind of exposure. It will have a long-range impact." Above all, he says, "Korea will be discovered as a country that's really important".

By the time the world leaders give their farewell press conferences next Friday after two days of haggling, the summit will have met the highest expectations of South Korea's president Lee Myung-bak if only the leaders can agree on an "action statement" that has real meaning.

The South Korean government, as CFred Bergsten, the director of the influential Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, observes, "is entrusted with a monumental responsibility" as the G20 "starts to segue into steering the world economy for the long run, rather than simply as a fire-fighting brigade".

SaKong Il, the former finance minister who is the chairman of the presidential committee on the summit, is emphatic about the need for the summit to go down as a moment of glory. "We feel a great responsibility to make the Seoul summit another success," he says.

To accomplish this goal, the leaders need to deal with the issue of tremendous imbalances in global trade for which artificial exchange rates, such as that of China's currency, are partially responsible. Mr Bergsten has called on the US "to mobilise a multilateral coalition to press China to let its currency rise by the needed amount" - and stressed the role of the G20.

"This currency realignment," he says, "is an integral part of the global rebalancing strategy adopted by the G20 and laid out in detail as part of its new Mutual Assessment Process."

Mr SaKong is not worried by the prospect of double-talk among leaders such as Mr Obama and China's president Hu Jintao. In the quest for ways "to weed out global imbalances, there are different approaches and different views".

The priority is dealing with the danger of more shocks and worldwide repercussions. With that goal in mind, says Han Duk-soo, the Korean ambassador to the US, "Korea has listed the strengthening of the global financial safety net as a major item on the agenda."

It was co-operation between the G20 countries and the IMF that got the fund's executive board in August to increase the duration and amount of available credit to establish a "precautionary credit line" needed as "insurance against financing shocks".

Look at Greece and Portugal, says Choi Joong-kyung, an economic adviser to president Lee, naming small nations that could have used a helping hand from the IMF before their crumbling economies contributed to the chaos in Europe.

Long before economic troubles gave birth to the G20 three years ago, the rise of China was key to the transition from G7 to G20. China dominates the so-called BRIC countries - also including Brazil, Russia and India - but the others also demand respect. Russia occupies a special place for having managed, as the heartland of the former Soviet Union, to attend G7 meetings and then to join the club, turning the G7 into the G8.

Brazil, however, may be the wildest card in the deck. Brazil's finance minister Guido Mantega describes the pushing and pulling over monetary revaluation as a "currency war". He blames the US for printing ever more money and also for not bringing its US$1 trillion (Dh3.67tn) budget deficit under control.

The IMF leadership, given the go-ahead by finance ministers and bank governors in a tense-two-day session in South Korea's ancient Silla kingdom capital of Gyeongju last month, is instituting a long-awaited shift from over-represented to under-represented countries in decision making.

"One of the real issues," says Jeffrey Lewis at the World Bank in Washington, "is the challenge that rebalances or recalibrates the degree of European representation".

Over the next two years, the IMF is raising the quotas of emerging-market countries by more than 6 per cent while giving them two board seats currently held by Europeans. The leaders, beside the US, Japan and four European countries, now include the BRICs. The US remains at the top of the heap, China comes in third and India eighth.

"The IMF is playing an increasing role of being an 'honest broker,'" says Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the head of the IMF.

At the same time, the Seoul summit lays claim to one singular success. That's the emphasis on development that president Lee, a former chairman of Hyundai Engineering and Construction, has insisted on making a separate agenda item.

"As host of a group of 20 that controls 85 per cent of the money in a world in which 180 or so other countries still must vie for their pieces of the pie, " says Jeffrey Schott, a former US Treasury department official, "Korea is stepping on to the main stage of the world economy."