Trying to maximise the benefits that an economy can get from natural resources poses various challenges, and sometimes, those challenges are so big that natural resources transform from a blessing into a curse. This can happen in many ways, including the threat of armed conflict, a fate that the GCC countries have fortunately avoided despite the abundance of oil in the region. But what is the precise mechanism by which this form of conflict arises, and how do policymakers protect their economies from it?

At a fundamental level in an economy, there are two ways for an individual to improve their standard of living: resource production, and resource expropriation.

Resource production refers to creating value by manufacturing goods and delivering services that others voluntarily acquire in exchange for their own goods and services, or for money that can be used to purchase goods and services from third parties. Think of a fisherman catching fish, selling it in the market and using the proceeds to feed and clothe his family.

Resource expropriation refers to seizing the value created by others, by physical coercion, also known as banditry. It includes pirates boarding a ship and acquiring its cargo under the threat of violence.

Resource production is about enlarging the economic pie, whereas resource expropriation is about redistributing the pie without growing it, and possibly by shrinking it, as violence often destroys value – think of a burglar damaging your house as he steals your possessions. Therefore a successful economy will have as much production and as little expropriation as possible; how can we minimise banditry?

The incentive to expropriate others is based on two factors: the size of the prize, and the punishment in case of failure. All governments strive to punish those who seek to seize the property of others, but no legal system can provide perfect protection. The problem in resource-rich countries is that the prize – control of a precious mineral or fossil fuel – can be huge, meaning that bandits expend super-normal energy in an effort to control the resource.

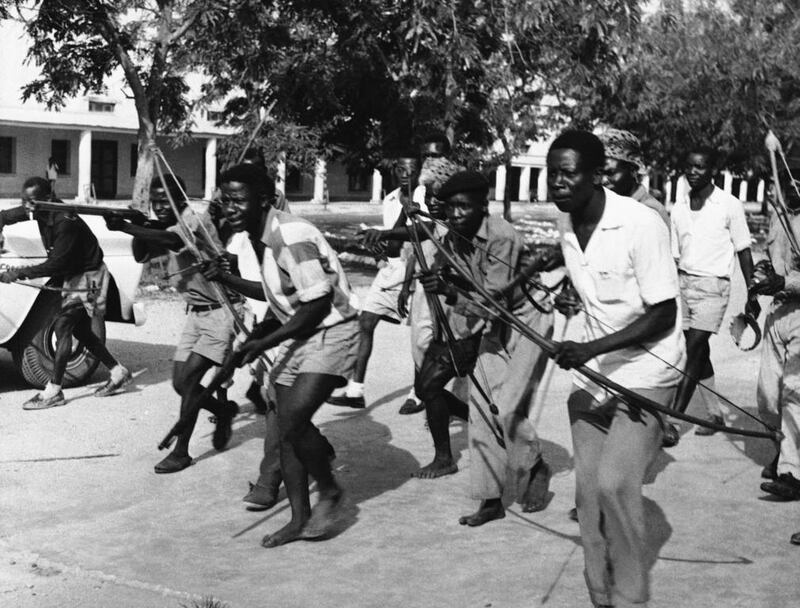

That is why many countries that have large endowments of natural resources contain multiple heavily armed militias, engaged in perpetual combat as they vie for control of resource revenues. An example is what befell Congo (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in the early 1960s, a crisis in which perhaps 100,000 people died.

The resulting deterioration in security is catastrophic for the economy: insecure property rights are a recipe for low investment in physical and human capital, and they greatly impair the economy’s ability to benefit from global trade and finance.

This problem is reinforced by the fact that many valuable natural resources, including oil, diamonds and gold, have productive processes that are capital-intensive and require only limited numbers of workers. This makes it easier for expropriators to quickly establish their own work teams, and limits the violent force necessary to generate revenues. In contrast, in countries such as Japan and Singapore that lack these types of resources, the easiest way to acquire wealth is to create it via cooperative and voluntary exchange with others. Trying to build PlayStations or operate banks by coercion would quickly result in an unprofitable and unsustainable enterprise.

Resource-rich countries such as Australia, Norway and the GCC countries have been fortunate to have had stable governments that emphasise property rights, halting would-be-bandits in their tracks. The resulting favourable security conditions have allowed for the attraction of foreign capital, and the investment of the natural resource wealth in improving the local economy.

Other, less fortunate countries have discovered natural resources during periods of poor governance, motivating groups to focus on violent expropriation as a way to improve their living standards, even if it comes at the expense of the economy taken as a whole. As the armed conflict increases in frequency, citizens will be left longing for the days before the discovery of natural resources, which is why the blessing of natural resources can sometimes turn into a curse.

Omar Al Ubaydli is programme director for international and geopolitical studies at the Bahrain Center for Strategic, International and Energy Studies, and an affiliated associate professor of economics at George Mason University. He welcomes economics questions from readers via email (omar@omar.ec) or tweet (@omareconomics).

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter