For a moment, the Trump administration thinks it has got the best from a bad oil situation. Opec and Russia will cut output, American oil production will fall naturally, the worst fallout from low prices will be averted while the few remaining motorists still enjoy cheap petrol.

But a lot of pain for the domestic industry is coming, risking some controversial, and probably bad policy choices.

The Opec+ cuts amount to about 7.4 million barrels per day from February's levels, before the short-lived production increase by Saudi Arabia, the UAE and others.

This has to contend with perhaps 25 to 30 million bpd of lost demand worldwide in April, and further large and continuing losses in May and thereafter.

In practice, some countries such as Iraq, Nigeria and Russia have rarely complied fully with their past quotas. Smaller members of the deal will "cheat" whenever they can amid fears that they might not be able to sell oil at other times and thinking their non-compliance will not really be noticed.

So, most of the adjustment to lower demand will have to be borne by economics and logistics as higher-cost producers and those serving limited local markets or at the end of long pipelines are forced to close in production.

That will affect inland US and Canadian crudes in particular. Bloomberg points to one grade, South Texas Sour, currently being bid at $2 per barrel.

This has domestic and international political implications. Most oil-producing states are Republican-leaning. Mid-western swing states benefit from the associated industries to petroleum, such as steel pipe and frac sand producers, but they also prefer cheap petrol.

Much of the US's recent foreign policy – such as sanctions on Iran, Venezuela and Russia, as well as the reduction of its presence in the Arabian Gulf and convincing China to agree to buy more American goods – has been based on the belief that its newfound "energy dominance" and status as a net oil exporter is permanent.

A collapse of its upstream petroleum industry would recall past traumas of energy insecurity.

Harold Hamm, chairman of Continental Resources, a shale-focused producer in North Dakota and Oklahoma, is a frequent confidant of Mr Trump and vocal advocate for protectionism.

In a more than ten-hour hearing on Tuesday, the Texas Railroad Commission, the state’s petroleum regulator, heard testimony on whether to impose “pro-rationing” – limits on oil production.

Mr Hamm spoke in favour of a 25 per cent cut. One method could be to limit the flaring of unwanted by-product gas, bringing an associated environmental benefit. But there are political, legal and practical barriers to pro-rationing, and it will not rebalance the market.

The Energy Department has even drafted plans to pay companies to leave oil in the ground, as a kind of strategic reserve, but this needs Congress to approve funding.

Setting a precedent for government interference is a risky move for the oil industry, with a pro-environmental Democrat potentially entering the White House next year.

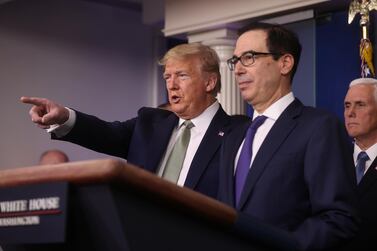

Donald Trump has shown a predilection for tariffs, which could be applied to imported oil. Other options include an outright embargo on imports from some countries blamed for oversupply – Russia and Saudi Arabia – though this has receded now they have agreed to cut production.

As recently as last April, a "Nopec bill" to enforce US antitrust action against Opec was gaining traction in Congress. By last month, senators had turned to blaming Opec for not colluding to raise prices.

What happened the last time the US went from being a net oil exporter to importer? The post-war consumption boom and a flood of cheap crude from Venezuela and the Middle East made it a net importer by 1949.

This triggered many similar national security arguments to those going on today. But at its heart, the issue was protection for oil states and smaller independent producers.

In 1959, the Eisenhower administration created a programme to limit imports, initially to 12.2 per cent of domestic production. After the 1973 oil shock, the country imposed tariffs on imported oil between 1975 and 1979, and banned imports of Iranian crude in 1979.

These measures spawned many exemptions and workarounds. One effect was higher domestic prices, supporting higher output and faster depletion than would otherwise have been the case. Another was a glut outside the US, a development that was a catalyst to Opec's formation in November 1960.

Such restrictions or tariffs today would be highly problematic. In 2019, the US imported about nine million bpd of crude oil and refined products while it exported 8.6 million barrels.

In recent months, it had become an exporter on a net basis.

Most American crude is light and sweet (low sulphur) and the country has to import heavier crude to get a suitable blend for refining, yielding enough diesel and jet fuel.

That has been exacerbated by the coronavirus shutdown, which has slashed demand for petrol, a light product.

A simple embargo on certain countries’ exports would just shuffle shipments around. For political and logistical reasons, the US could not step up imports from Mexico, Venezuela, Canada or Iran. That means it would have to import more from Brazil, Kuwait and Iraq.

Tariffs would push up prices for US consumers. They would have to apply to all refined products and would make the country's petroleum exports uncompetitive.

Like the dismal Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which put in place protectionist trade policies in the US and arguably deepened the Great Depression, tariffs would further smother world trade.

Countries such as Mexico and Canada, which send crude to the US and import refined products, would probably impose retaliatory duties.

Tariffs would harm relations with countries such as Saudi Arabia, which in 2017 took full control of Port Arthur, the largest US refinery, as an outlet for its crude.

The reality is that much US oil production is simply uncompetitive and can survive only when demand is solid and Middle East and Russian output limited.

Washington can fudge that reality with measures that inflict more long-term economic and international harm. Or it can behave like a superpower rather than a one-trick plutocratic petro-state.

Robin M. Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis