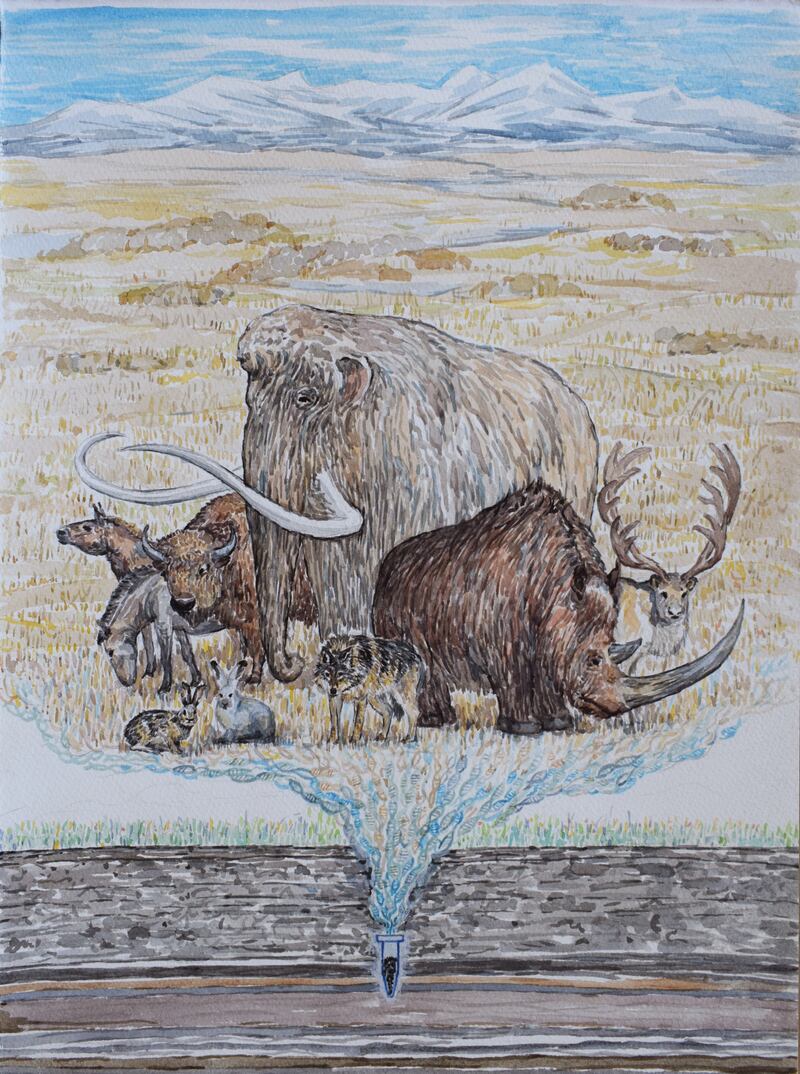

One of the most curious exhibits at Cop28 in Dubai last November was the “Pleistocene Park” backed by Russian coal and fertiliser billionaire Andrey Melnichenko.

He thinks that restoring lost ecosystems could be the way to take up more carbon from the atmosphere.

Biodiversity is part of climate, and yet more than that. The question is how can we best preserve and restore the natural world?

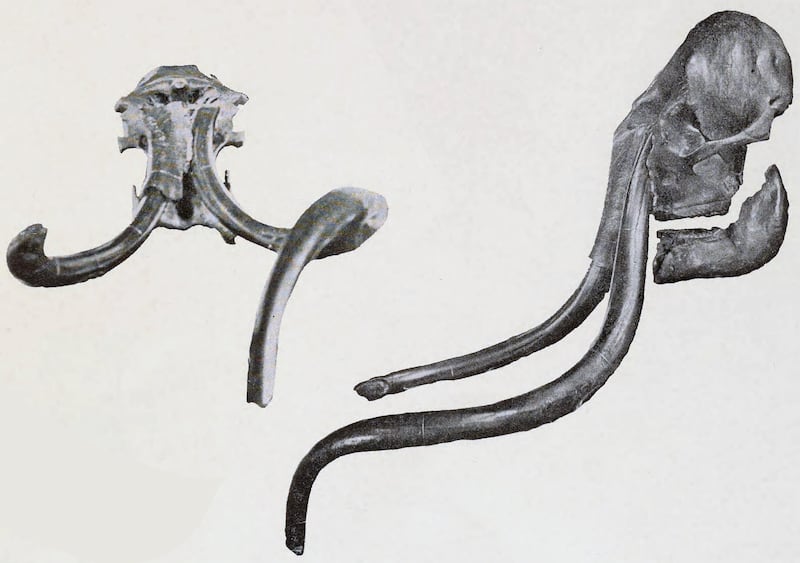

Mr Melnichenko has made a start by funding the return of some large mammals, including horses, reindeer and musk-oxen, to a remote north-eastern corner of the Russian taiga and tundra. He has not yet revived the mammoth, which became extinct shortly after the end of the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago, though there are some proposals to use genetic samples preserved in permafrost.

Nevertheless, he believes that by trampling snow and recreating grassland, the animals will help the tundra store more carbon and slow the melting of permafrost.

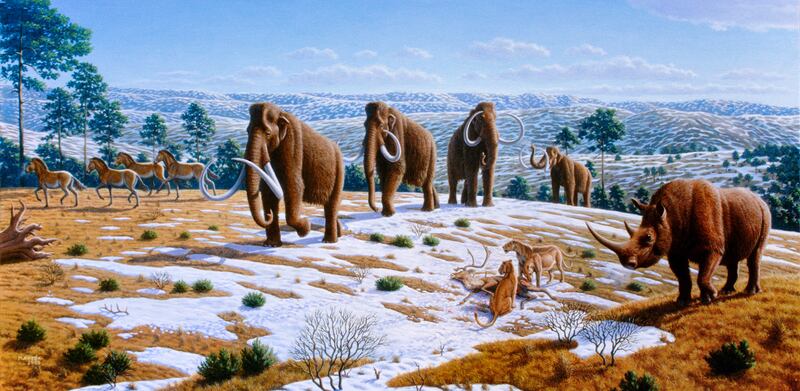

Large, “charismatic” creatures such as dinosaurs and mammoths are those we most wish we could bring back. Conservation efforts for endangered species focus on the white rhino, the panda, the orangutan and similar species.

Visiting a wildlife park such as Kenya’s Nakuru, Zimbabwe’s Hwange or Sri Lanka’s Yala reveals a rich variety of animals such as elephants, lions, leopards, hippopotamuses and crocodiles.

However, these are but vestiges of former paradisiacal ecosystems, that spanned every continent before the arrival of modern humans.

Their advanced hunting skills, the clearing of forests by fire, perhaps in combination with the climatic changes at the end of the last Ice Age, wiped out the mammoth along with the sabre-toothed tiger, the woolly rhinoceros, giant kangaroos and others.

Then came the takeover of land for agriculture, and the onset of invasive species that accompany people, such as dogs, cats and rats.

The modern era has seen further encroachment, industrial-scale forest clearance, the slicing up of habitats by roads for logging and mining, noise and light pollution that drive animals away and interfere with mating patterns, the overuse of pesticides and fertilisers, and the flooding of valleys by hydroelectric dams.

Climate change now threatens to outpace the rate at which species can adapt or move to cooler climates. Acidification of the oceans by carbon dioxide combines with industrial fishing, coastal development and excess nutrient run-off to devastate coral reefs, an essential building block of marine ecosystems.

In some studies, the Amazon rainforest appears dangerously close to dieback, when it would convert to savannah, releasing large stores of trapped carbon into the atmosphere – equivalent to about 13 years of emissions from all fossil fuel combustion.

Meet the wild bison fighting climate change in the UK

Today, humans amount to 34 per cent of all mammal biomass; our domestic creatures – mostly cows, pigs, sheep and chickens – for 62 per cent. Wild mammals are just 4 per cent.

For all the focus on the big charismatic animals, the effect on less visible parts of the ecosystem may be more important – plants, insects, birds and amphibians.

British scientist James Lovelock, who died in 2022 aged 103, created the hypothesis of “Gaia” – that the Earth and life upon it form a unified, self-regulating organism. But he came to fear that so much biodiversity had been destroyed that Gaia might lose its ability to adjust and recover.

If the living world started releasing rather than absorbing trapped carbon, that would be a devastating blow to our ability to limit climate change.

Yet we are putting a growing burden on the natural world. Not so much because of overpopulation, an unhealthy obsession of some mostly western scientists and campaigners who fixate on developing countries. The problem comes more from the growing needs for food, timber and – ever more – biofuels.

Air transport, in particular, plans to rely on sustainable aviation fuels made mostly from biological materials – waste at first, such as used cooking oils, but once that supply is exhausted, attention will turn to dedicated crops.

But much renewable electricity, particularly in Europe, comes from burning biomass – particularly wood. This has dubious sustainability, and, as trees take time to grow after being replanted, may occur a carbon debt that takes decades to repay.

The International Energy Agency estimates the current energy from biological material at just over 60 exajoules – equivalent to about 10 per cent of world demand for primary energy, or about half the energy consumption of North America.

While a large share of “traditional use” – often unsustainable cutting down of trees for firewood if it rose to over 100 exajoules by 2050 would stop, some of this comes from re-using waste.

The agency has carefully tried to keep its estimates within the bounds of sustainability, but other studies reveal much higher figures.

We should seek to tread more lightly on the earth rather than more heavily. That suggests initiatives of rewilding – returning some arable or pasture land to nature, restoring habitats such as mangroves, re-establishing populations of large mammals, and allowing predators such as bears and wolves to return.

Agriculture should be more intensive but over less land, and with more focused attention on managing its negative consequences, such as fertiliser overuse, run-off, and water withdrawals.

Over-reliance on biomass for low-carbon fuels can be replaced by hydrogen-based synthetic fuels using renewable energy or carbon capture and storage. Biomass power plants can be downplayed in favour of nuclear and geothermal power, batteries and hydrogen or carbon capture-based generation.

Restoring biodiversity goes beyond the problem of climate change. Some of the proposed ways of tackling climate change may be very damaging to biodiversity, while others favour it.

Pleistocene Park may be an extreme example, but the integrity of ecosystems should be cherished, not trampled under the hooves of a one-eyed climate policy.

Robin M. Mills is chief executive of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis