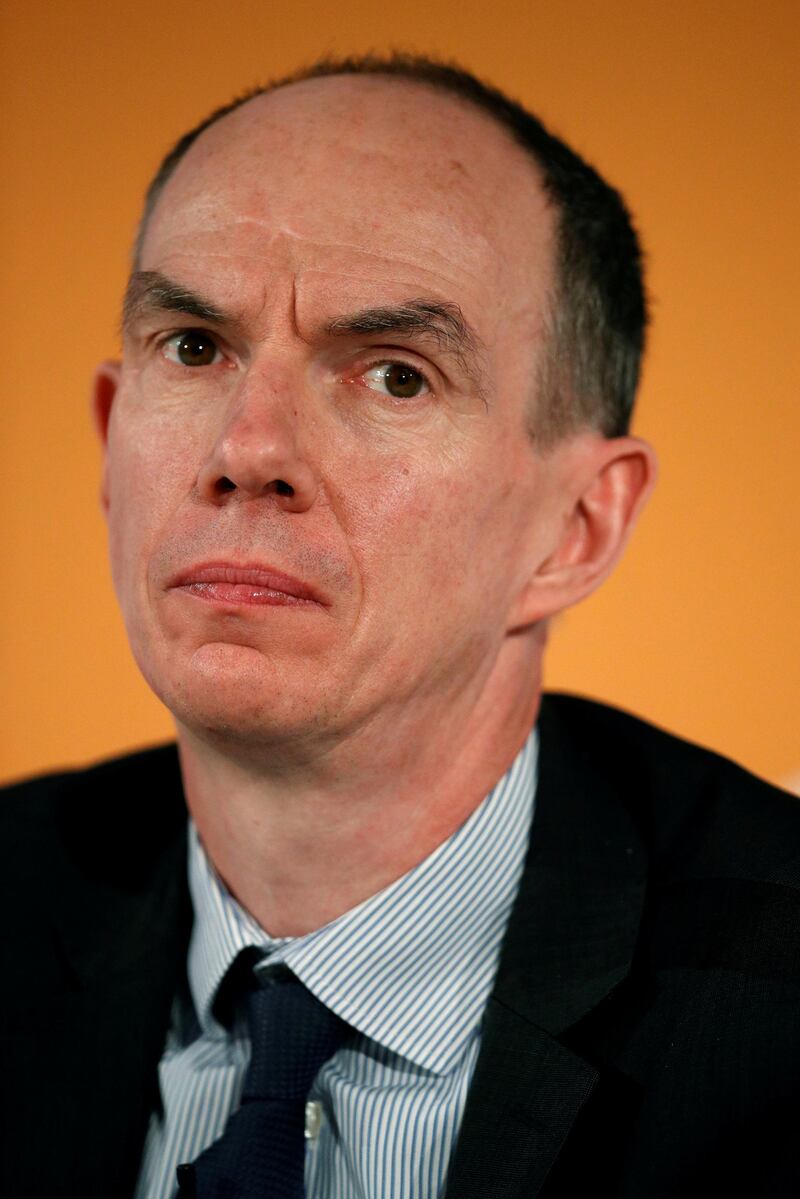

The Bank of England might need to raise British interest rates somewhat sooner than deputy governor Dave Ramsden had expected if wage growth picks up early this year, according to a newspaper interview released on Saturday.

Mr Ramsden was one of two policy makers who opposed the BoE's decision in November to raise interest rates for the first time in a decade, but appears to have shifted his stance somewhat in comments published by the Sunday Times newspaper.

"We all will keep a close eye on what happens through the early part of this year to see if that [BoE] forecast of wage growth picking up to 3 per cent is realised," Mr Ramsden was quoted as saying.

“But certainly relative to where I was, I see the case for rates rising somewhat sooner rather than somewhat later.”

Economists polled by Reuters expect the BoE to raise interest rates to 0.75 per cent from 0.5 per cent by May, and financial markets price in a high chance of a further rate rise to 1 per cent before the end of 2018.

_______________

Read more:

UK economic growth revised down as consumers hit by inflation

Bank of England chief dismisses Bitcoin

_______________

The BoE's chief economist, Andy Haldane, told policy makers on Wednesday he thought interest rates might need to rise slightly faster even than the central bank had expected when it set out fresh economic forecasts early in the month.

But governor Mark Carney said at the same event that future monetary policy decisions would depend heavily on how businesses and consumers react to ongoing talks on the terms of Britain’s departure from the European Union in March 2019.

Britain’s economy underperformed compared to other major advanced economies last year due to a hit to consumer demand from higher inflation triggered by the pound’s fall after the Brexit vote, as well as comparatively weak business investment.

The unemployment rate also rose slightly in the final quarter of 2017, though at 4.4 per cent it remains near a 42-year low.

Mr Ramsden told the Confederation of British Industry on Friday that the economy could not grow faster than 1.5 per cent a year without starting to add to inflation pressures.