If you have ever flown in a commercial jet over the past few decades, it is most likely to be a Boeing 737.

The US plane maker has sold a big number of them since 1965 – in fact, the figure comes in at little less than 15,000. By comparison, Boeing's second-best-selling aircraft, the wide-body 777, has received less than 2,000 orders.

So one would assume every aspect of the smaller plane's operations have been thoroughly tested, and any potential issues have long since fixed. Yet, as Boeing was developing its latest version of the 737, it discovered the design was slightly more prone to a loss of control.

So the company added a computer-powered safety feature – one that has become the focus of an investigation into a fatal crash in October near Indonesia.

The crash of the Lion Air 737 Max 8 may end up as one in a number of cases in which the cockpit automation that has made flying safer has also had an unintended consequence of confusing pilots and leading to tragedy.

Investigators considered the possibility that the new anti-stall system that repeatedly pushed the Lion Air jetliner's nose down was fed erroneous data from a faulty sensor left in place after a previous hazardous flight.

Boeing has said cockpit procedures that were applied on the previous flight are already in place to tackle such a problem. But US regulators have said the plane maker was also examining a possible software fix, after coming under fire for not outlining recent changes to the automated system in its manual for the 737 Max.

The pilots in the Lion Air crash did not follow an emergency procedure that could have deactivated an automated feature and allowed them to fly normally, reported investigators. A different pilot crew the night before the accident had effectively shut it off during an identical emergency and landed routinely.

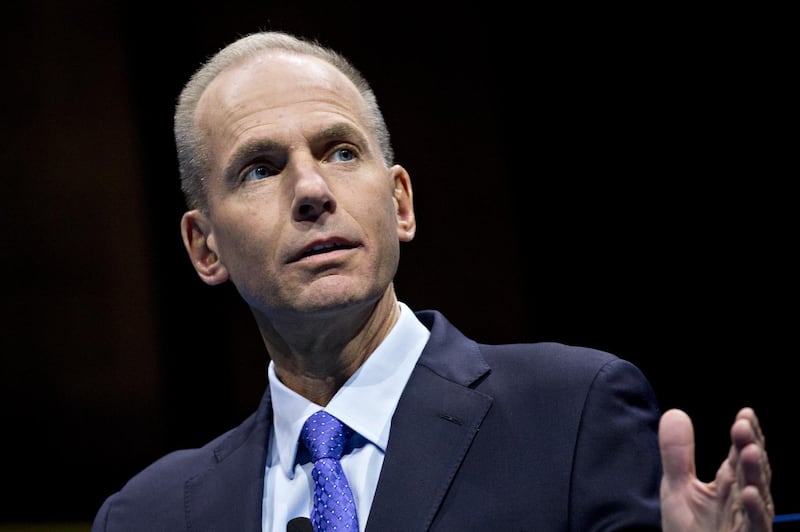

Boeing chief executive Dennis Muilenburg said this month he was “very confident” in the safety of the 737 Max.

"We know our airplanes are safe," he said. "We have not changed our design philosophy."

For decades, plane makers have been adding automated systems to help pilots set engine thrust, navigate with higher precision and even override the humans in the cockpit if they make mistakes. Airline disasters have become increasingly rare as a result, but automation-related crashes have become a growing factor in the few that do occur, according to government studies and accident reports.

“There’s no question that automation has been a tremendous boon to safety in commercial aviation,” said Steve Wallace, who served as the chief accident investigator for the US Federal Aviation Administration.

“At the same time, there have been many accidents where automation was cited as a factor.”

A 2013 report by the FAA found more than 60 per cent of 26 accidents over a decade involved pilots making errors after automated systems abruptly shut down or behaved in unexpected ways.

For example, pilots on Air France Flight 447 inexplicably made abrupt movements and lost control of their Airbus A330 over the Atlantic Ocean in 2009 after they lost their airspeed readings and the plane’s automated flight protections disconnected. All 228 people on board died.

The US National Transportation Safety Board concluded that pilots of an Asiana Airlines Boeing 777-200ER that struck a seawall in San Francisco in 2013 killing three while trying to land, did not realise they had shut off their automatic speed control system in part because it was not properly documented.

Pilots on Lion Air Flight 610 were battling multiple failures in the minutes after they took off from Jakarta on the early morning flight, according to Indonesia's National Transportation Safety Committee. The pilots had asked to return as they struggled but plunged into the Java Sea at high speed before they could land, according to investigators. All 189 people aboard were killed.

Data from the recovered flight recorder shows that the Max’s new safety feature, known as Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), was triggered. An errant sensor signalled that the plane was in danger of stalling and prompted the MCAS to compensate by repeatedly sending the plane into a dive.

The pilots counteracted by repeatedly flipping a switch to raise the nose manually, which temporarily disabled MCAS. The cycle duplicated itself more than two dozen times before the plane entered its final dive, according to flight data.

This occurred as multiple other systems were malfunctioning or issuing cockpit warnings. Most notably, the cockpit was permeated by the loud thumping sound of a device on the captain’s side of the cockpit known as a stick shaker, which is designed to warn the pilots they are in danger of losing lift on their wings. The stick shaker was erroneous, too, prompted by the same false readings from the sensor.

_______________

Read more:

Boeing sees continued growth of aircraft financing to $143 billion in 2019

Bombardier sees shift to ‘growth cycle’ on new luxury jet

_______________

Boeing stresses that a procedure pilots train for should have overcome the malfunction. "Automation is an aid to flight crews on our airplanes and is a significant contributor to improving safety," the Chicago plane maker said.

Airline accidents almost never occur from a single cause and preliminary information from the investigation suggests multiple factors were at work on the fatal Lion Air flight.

While maintenance and pilot training may be found to be more significant, the underlying issue with an automated system behaving in unexpected ways puts the accident in a now-common category.

Plane makers have been adding more automation to help pilots avoid errors as aviation technology has become increasingly sophisticated.

At Airbus, flight computers oversee pilots’ control inputs on models built since the late 1980s and will not allow steep dives or turns deemed unsafe. Boeing’s philosophy has been to leave more authority in the hands of pilots, but newer designs include some computerised limits and, like Airbus, its aircraft are equipped with sophisticated autopilots and systems to set speed during landings, among other functions.

The new feature on the 737 Max family of aircraft was designed to address one of the most common remaining killers in commercial aviation. By nudging the plane nose down in certain situations, the MCAS software lowers the chances of an aerodynamic stall and a loss of control.

Accidents caused by failure to control killed 1,131 people between 2008 to 2017, by far the biggest category, according to Boeing statistics.

This type of automation is credited with helping create the unprecedented safety improvements of recent decades, yet it has not been perfect.

“A lot of the experts have commented that human beings are not very good at monitoring machines,” said Roger Cox, a former NTSB investigator who specialised in pilot actions. “The reverse is better. Machines are pretty good at monitoring human beings.”

Devices that offer relatively simple warnings of an impending mid-air collision, for example, have proven nearly foolproof, according to reports. On the other hand, more complex systems that aid pilots but require human oversight have on rare occasions confused crews and led to crashes.

It is also important to keep in mind that issues with automation can be exacerbated by pilot actions, Mr Cox said.

“Often times, what we call an automation error is really a proficiency error or a lack-of-attention error and not fundamentally a fault of the automation,” he said.

At least one reason that these type of accidents occur may have to do with how pilots’ manual flying skills atrophy as cockpits become more automated, according to a 2014 study by Nasa research psychologist Stephen Casner.

While basic tasks like monitoring instruments and manually controlling an aircraft tend to stay intact in the automated modern cockpit, the study found “more frequent and significant problems” with navigation and recognising instrument system failures.

A different study by Mr Casner and others in 2013 found a similar issue: “flying has got so safe that pilots don’t experience emergencies much during regular operations, if at all. That is good news in the main, but it means that crews also are not as prepared”.

The study suggested that airlines devise more realistic and complex training scenarios, and that they give pilots more practice reacting to emergencies that occur while automation is off.

“Where novices are derailed, discombobulated or taken by surprise when problems are presented under novel circumstances, experts characteristically perform as if they have ‘been there and done that’,” the authors said.

In the wake of the Lion Air crash, aviation authorities in Indonesia and India have pushed for more simulator training for Boeing 737 Max pilots, Reuters reported. Indonesia said this month it will immediately impose new requirements for simulator training.

"In the past there were three hours of computer-based training," Indonesian air transportation director general Polana Pramesti said, in reference to requirements for pilots switching from older versions of the 737.

The Lion Air crash could have serious implications for Boeing's bottom line. The budget airline has confirmed it is considering cancelling Max orders worth $22bn.