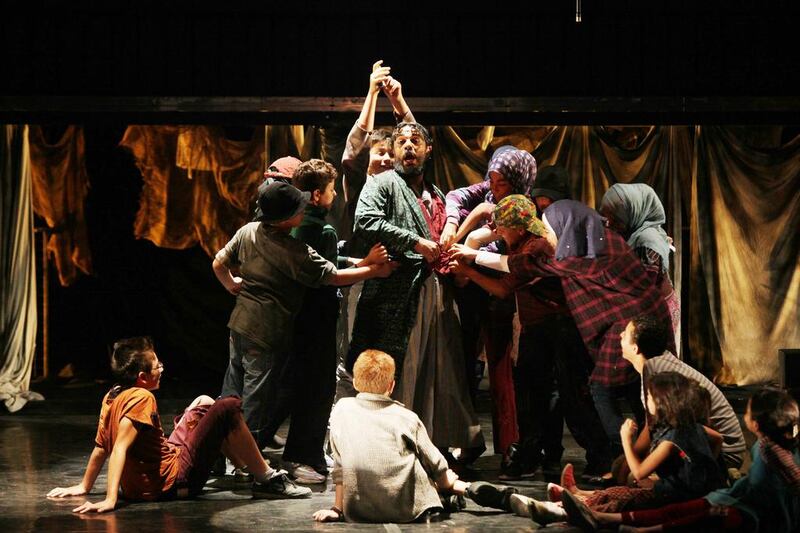

There were 17 hungry children in worn-out clothes banging on the orphanage tables as they demanded kebabs, chicken and ful fava-bean stew.

What they got did not even begin fill their empty stainless steel bowls, so one hungry orphan, a red-headed boy called Oliver, demanded more – and that was his crime.

This was how the first Arabic language adaptation of Oliver! opened on a stage in Amman last week, with an amateur cast of adult Jordanians and Syrian refugees.

The British musical, written and composed by Lionel Bart, is based on the Charles Dickens classic novel Oliver Twist, which exposed the poverty, hardships and cruelty meted out to orphans, in London in the early 19th century, as well as the practice of child labour.

While this Middle East production of the musical was featured in a contemporary Arab city rather than Victorian London, the novel’s themes still resonated.

This Oliver, was played by Fadi, a Syrian child. After being thrown out of the orphanage for his insolence, he is sold to an undertaker, who changes his name to “beggar” in Arabic, hurls insults at him by the dozen and forces him to clean the parlour that contains a black coffin and photographs of the dead. Labelled a street boy, he has only scraps of food to eat and sleeps on the floor.

For the children in the cast, it was their first encounter with the classic musical but, despite their young age, tragedy is something they are already familiar with.

While none of the young actors was orphaned in real life, all had lost homes in Syria, had witnessed death and destruction and were unable to account for family members. The war had traumatised them.

There were twins with a missing brother and a child whose sister lost her baby after exposure to sarin gas two years ago. Another had seen his father struck by a bullet as they escaped to Jordan.

This production, which ran for three days last week, was co-produced by a British couple, Charlotte Eager, a filmmaker and contributing editor at Newsweek magazine, and William Stirling, a filmmaker and communications consultant. The director was Georgina Paget, who was involved in a Syria adaptation of the Trojan Women.

It was adapted to fit a modern Arab capital by Egyptian actor and director Kahled Abol Naga. He adapted the script to a modern Arab city because it was felt that circumstances of Syrian child refugees were similar to the conditions exposed by Dickens.

Oliver Twist, Naga says, was: “a slap in the face for Victorian England”, with the Arabic adaptation a: “Slap in the face of the Arab community today, so that society will no longer perceive children as a burden but a source of pride.”

Jordan has 630,000 Syrian refugees registered with the United Nations agency and more than half are under the age of 18. The vast majority live in urban communities, struggling to make ends meet.

Their savings are depleted, and the further cuts to food assistance vouchers in July by the World Food Programme have added to the misery of hundreds of thousands trapped in poverty.

Already home for several waves of refugee, starting with Palestinians in 1948, Jordan is struggling with it own economic hardships. The influx of Syrians has strained the country’s scant resources and has lead to rising tensions, particularly in urban communities where the refugees are concentrated.

Child labour among Syrians is on the rise, with children giving up school to support their families.

In Zaatari camp, home to 80,000 refugees, and now effectively Jordan’s fourth largest city, nearly half of all school-age children are out of education.

A Unicef and Save the Children report released in July this year shows that in Jordan a majority of working children in host communities worked six or seven days a week, with one-third working more than eight hours a day.

Their daily income is between US$4 (Dh14.69) and $7. Children also start working very young, often before the age of 12 and are exposed to harmful conditions. About 75 per cent of working children in the Zaatari refugee camp reported health problems.

The conflict, now in its fifth year and with no end in sight, is placing an entire generation of Syrian children at risk.

“We wanted to get the message out on what’s happening to the Syrian refugees and what happened to the Jordanian host community,” says Eager.

“Jordan has welcomed three waves of refugees in the last generation and a half. It is a small and not a rich country. Syrian refugees have depressing and sad lives, which is no longer in the news.”

The Arabic adaptation tackles themes from child poverty to forced labour, hunger, abandonment, street gangs and domestic violence.

In one scene, Oliver, lonely and abandoned, sings: “Where is love?” In another song, the cast tells Oliver to “consider yourself at home. Consider yourself one of the family”. Although the song was about welcoming, “It had a dangerous element,” says Eager, “because he was in the wrong place.”

Those familiar with the musical will recall the lines: “Got to pick a pocket or two,” as Oliver learns how to steal when he is taken in by a street gang and led to their master’s hideout.

He is an innocent and this criminal act is presented to him as perfectly normal, Eager says.

Despite the grim realities depicted in the musical, it has a happy ending. The man Oliver tries to pickpocket turns out to be his long lost grandfather with whom he is reunited.

The children have identified with the characters in the musical and say it has touched them.

One told Eager: “This production of Oliver! touched something in my heart and changed it but I cannot describe what it has done.”

Fadi, who plays Oliver, says the choice of the play was: “Great. Oliver is a kid fighting for his rights just like me.”

Ibrahim, a Jordanian boy who plays the Artful Dodger, says he really identified with the character. “I am from the ghetto,” he said. “I am from Hashmi and there are a lot of street kids like me.”

Hashmi is a rundown neighbourhood, where many Syrian and Iraqi refugees live.

Eager and her husband have been involved in several drama therapy projects for refugees. Two years ago, they spearheaded a project for slum children in Nairobi and were co-producers on the Trojan Women, an Arabic production of Euripides’ great anti-war tragedy with an all-female cast of Syrian refugees in Jordan.

It took a year to bring Oliver! to fruition, says Eager, but the serious work started in February. It involved drama and music therapy workshops at a community centre in Amman. Starting with a hundred underprivileged children and refugees, they settled on 36 children who could sing.

Reem Assayyah, the project manager, says that while there are children have endured worse circumstances than Oliver, “there is still hope. And this is the message the play is trying to relay”.