Recently, an empty shop under renovation in downtown Cairo became an impromptu theatre for an unusual performance. An audience of about 12 people sat on mismatched chairs. A few well-placed scarves and portraits of Shakespeare and the Syrian satirical writer Mohammed al Maghout formed the backdrop. Two identical young men suddenly appeared and began reciting overlapping Shakespeare monologues in Arabic. The Malas twins, Ahmed and Mohammed, are 26-year-old actors and playwrights. Their play Melodrama, originally performed in their bedroom in Damascus, has become an underground sensation in Syria. During a visit to Cairo, they organised three performances. In the play, Shakespeare quickly devolves into an argument between the two characters, the grey-haired Abu Hamlet (played by Mohammed) and the boisterous young Nejm, or "Star" (played by Ahmed). They are aspiring actors living in shared quarters who spend their time recounting disappointments, venting frustrations and indulging in fantasies about making it big. As their names suggest, the characters represent different generations of the Syrian acting community - the older committed to the theatre, and the younger enamoured with television and cinema. When the Malas twins were 16, they saw a play together and "decided we must become actors", Mohammed says over coffee the next day (he could just as well be Ahmed; the twins often wear matching outfits and have a habit of finishing each other's sentences). But their application to the highly competitive Syrian High Institute of Theatrical Arts was rejected three times. "They told us: 'You're not talented, you won't be actors.'" Syria has a long and illustrious theatrical tradition and a burgeoning movie and TV industry that has resulted in some very popular and well-produced TV serials of late. The brothers auditioned for TV and film parts but never got any major roles ("For TV, you need connections," Ahmed says), and ended up working full-time at the children's theatre in Damascus. The twins channelled their frustrated ambitions into Melodrama, a play that is as self-referential as you can get: actors portraying actors who spend the play talking about acting. There is no plot, just a whirlwind of allusions to high art and pop culture. The play, Ahmed says, "is a mix of 10 years of what we saw and read". Apart from Shakespeare, there are references to Samuel Beckett (to whom the play owes an obvious debt), Russian novelists, Syrian actors and the Lebanese singer Fayrouz. The characters enthusiastically enact a Bollywood musical number and show off their singing and fighting skills. Product placement is made into an ongoing joke as the characters keep sipping a drink prominently labelled "melo" (as in "melo-drama"). The play uses familiar postmodern techniques: the characters are unreliable; the plot (if you can call it that) is cyclical; time and place are fragile conventions (at the end of the work, Abu Hamlet and Nejm discover that their clock has stopped and the exit to their room can't be found). But the narrative in-jokes don't stall the play, which is propelled by the Malases' fluid, energetic performances. The brothers are deft physical and verbal comedians, and have absolutely no trouble holding the audience's attention during the one-hour run. The humour is playful and often absurd, based on free association, wordplay and light-handed slapstick. If the play has a serious kernel of a subject, it is the frustration of going nowhere, the gulf between one's aspirations and one's reality. It's about "trying to reach something you desire", Ahmed says. "There are many young people who try like we do and fail." In the show, Abu Hamlet recounts how someone from the Syrian intelligence service came to see him perform Moliere: "He wrote a report on me, and the show turned from a comedy into a tragedy." So Abu Hamlet decides to become a tragic actor, but this doesn't turn out as planned, either. While he cries on stage, the audience laughs. "In the end," he concludes, "I started to cry over my situation and the absurd life I lived? And then I decided to work in absurdist theatre..." At another point, Abu Hamlet says: "We loved art; we got ridiculed. We loved love; we got broken. We loved life; we went bankrupt. We loved death; we lived? We loved discussions; we got into fights. We loved food; we went hungry. We loved freedom; we got jailed. We loved cats; we got scratched." During the Cairo performance, passers-by wandered in. Three boys sat in a corner, wide-eyed. The sounds of footsteps and conversations wafted across the shop's threshold. Fans and the gutted shop's high ceilings kept the late afternoon Cairo heat just barely at bay. The Malas twins are used to non-traditional performance spaces. In Cairo, they handed out a flyer that listed their previous shows, including 54 performances "in a room at home". The idea of writing a play to be performed in their bedroom came to the brothers after they saw Samir Omran's play The Two Emigrants in an underground shelter that held no more than 40 people. Their room was a much tighter squeeze: no more than 10 people could fit on the three couches they arranged there. They performed the play for the first time on February 2 in a one-square-metre space in the middle of the couches - a space so small that they are currently candidates for the Guinness Book of World Records. The decor cost less than $10 (Dh36), and consisted mostly of a few scarves hung from the ceiling fan. The musical accompaniment was played from a cell phone. The audience members sat so close to the performers that they sometimes had to shift out of their way. Eventually, word about Melodrama spread, and figures from Syria's cultural establishment came to see what all the fuss was about. The play was written up in the Syrian press and covered by Arab satellite TV channels. It is often touted as an example of pluckiness, a return to the pure, non-commercial principles of the theatre. It's also seen as something that gives voice to the frustrations of a generation of young people with few opportunities and creative outlets. The piece has now been performed at theatre festivals in Homs, Latakia and Amman, and in a number of large cafes. The twins are hopeful that they will be included in other official events. They say Syrian -government officials have approached them wanting to sponsor performances. The brothers were in Cairo to organise the Egyptian premiere of their play and to collaborate with the visual and video artist Doa Ali on her next project. She had seen them perform in Amman and was taken by "their rhythm together, how they react to each other, their energy together. They're very attractive in a classical way. They look like characters in a 19th-century novel", she says. The Malas twins performed Melodrama three times in Cairo, sticking to the kinds of intimate, informal spaces they are accustomed to. One show was staged in Ali's studio, -another in the empty shop downtown, and the last at an apartment used by the Egyptian theatrical group Al Warsha. "This play is really the beginning for us," Mohammed says. "It's what's made us take off." In person, the twins are soft-spoken and funny, a mix of humility ("We believe in God; he'll give us our opportunity, not any person or company") and disarmingly naive ambition ("Our goal is Hollywood"). Despite the bare-bones approach to Melodrama, the brothers are not purists: their stripped-down first project was a strategic as much as an aesthetic choice. They have followed the careers of the few Syrian -actors to have become known internationally (such as Ghassan Massoud, who played Saladin in Ridley Scott's Kingdom of Heaven) closely. They are enthusiasts of extremely disparate works, from the Iranian director Majid -Majidi's films, to Jackie Chan flicks and Hollywood blockbusters such as Gladiator. In fact, their omnivorous enthusiasm for acting in all its forms - and their frank approach to the yearning of actors for fame and fortune - is part of what gives their play its charm and animation. Mohammed sums up their plans for the future: "Syrian theatre, Egyptian cinema, Hollywood." The twins make a point of mentioning that, in anticipation of action films, they already have black belts in kick-boxing. There is a sequence in Melodrama in which Abu Hamlet and Nejm attempt to speak English to each other to practice for an American debut: Abu Hamlet (in heavily accented English): What's your name? Nejm: Very good. Abu Hamlet: Fine. Nejm: How old are you? Abu Hamlet: I am Fathers Hamlet, wa you? The characters then get into a disagreement and quickly resort to Arabic to settle their differences. But the Malas twins, who say improving their English is one of their priorities, plan on being much better prepared than their characters when their big break comes.

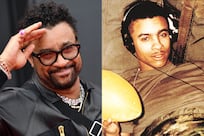

Stage props

A play that two aspiring-actor brothers began performing in their home six months ago has become an underground sensation in Syria.

Editor's picks

More from The National