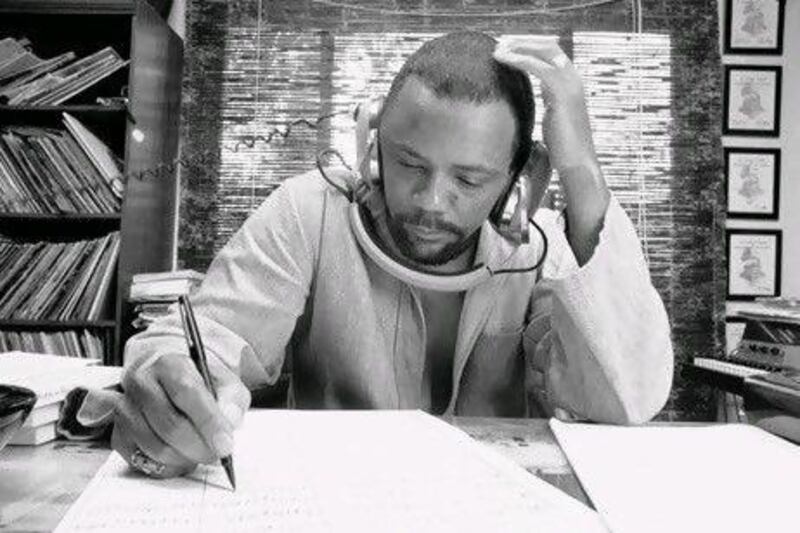

The legendary music producer Quincy Jones apologises for barking for clarification. He can't quite hear me. He says he is going a bit deaf.

"But what a way to go!" he enthuses, adjusting the dual earpieces that buzz like an old radio every time he tilts his head.

Jones's ears have led him on a musical odyssey that has included contributions to almost every significant moment in modern American music since the 1940s. He was playing trumpet for Billie Holiday at the age of 14. He was touring in Lionel Hampton's band at 18. He went on to play and arrange for Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra before helping nurture a new generation of artists such as Aretha Franklin and Lesley Gore. As if that weren't enough, Jones also managed to find time to write film scores that include In the Heat of the Night, The Italian Job and The Color Purple as well as landmark television themes such as those for Roots and Ironside. He accomplished all this before getting around to his career-defining work in the late 1970s and 1980s: stewarding Michael Jackson to global superstardom.

You imagine that sitting on the Grammy Awards panel meetings must be getting a little samey: all told, they've nominated Jones 79 times.

Jones, who just turned 78, is putting his phenomenal music and management skills to the test again. He has served as executive producer on Q: Soul Bossa Nostra, an album of songs from his 60-year career, re-recorded by a disparate band of high-rollers and divas including Mary J Blige, Amy Winehouse, Snoop Dogg, Usher, Jennifer Hudson, Akon, Jamie Foxx and BeBe Winans. It is quite a vision: the gospel singer, the gangsta and the diva all bowing down in homage to Jones.

"I guess they are aware I kinda lived through the birth of American music." Jones says. "Man, I was in the delivery room! They came, they performed and they stayed to hear me tell a story or two."

And the album's singers aren't the only ones to benefit from Jones's nurturing of talent. It was announced last month that he is joining the UAE entrepreneur Badr Jafar in the joint venture the Global Gumbo Group, which aims to create more live entertainment opportunities for western artists in the Middle East and North Africa. The group will also look to support new talent from the Mena region, and to acquire content to introduce to the West.

"I have long been a vocal proponent of music and the arts being a great asset in building bridges between cultures," Jones says, adding that he hopes to "foster a better understanding of these regions and an appreciation for our common values at this crucial time in the region's history."

Today he sits in London's Dorchester Hotel sporting simultaneous dress codes that reflect his life journey: the elder statesman (blue pinstriped suit), the boho jazz man (a funky, multicoloured knotted scarf, gold dog tags round his neck and a gold hoop earring) and the grandfather (a pair of slippers).

Q: Soul Bossa Nostra confirms Jones as an elder statesman with a unique leverage among several generations of musicians and singers. Who else could get Winehouse into a studio to rework, apparently unironically, It's My Party, the No. 1 hit Jones produced for Gore in 1963. Jones won Winehouse over with a special family recipe.

"I said: 'You eaten a rat before? I'm telling you it's like any other meat. I was seven years old and my grandmother would send me and my brother out to get the fat ones. The ones wriggling their tails are most tender.'"

He relates the tale, waits for you to be sick inwardly and then chuckles: "It's true. It's not a bad meal. When you throw in some onions. And when you get over it being a rat."

As children Jones and his brother Lloyd were sent to live with their paternal grandmother, a freed slave who could still recall African words, living in Louisville, Kentucky. And yes, he and his brother caught rats and she fried them. Their mother, Sarah, had suffered a breakdown and been admitted to an asylum.

Jones's father (also Quincy), a carpenter working for Chicago gangsters, eventually retrieved the boys and took them to Seattle. Jones became a teenage gangster who carried a knife and even a snubnosed .32-calibre gun that he still owns. Music provided his way out. When he was 13 he learnt that Count Basie and his orchestra were in town, so he sought out the trumpeter Clark Terry and asked for lessons before school each day.

"Music was something I could practise and control and make sense of," he says.

By the age of 15 he was in the Bumps Blackwell Junior Band, who were asked to back visiting superstar Billie Holiday in concert.

"We were kids and so awestruck by this woman who was as famous as Michael Jackson then, we almost forgot to play," Jones says.

At 18 he had won a scholarship to Berklee College of Music in Boston and found some paid arranging work in New York. Suddenly he was in bars and clubs hanging out with Sarah Vaughan, Art Blakey, Charles Mingus and Miles Davis. One night he met Charlie Parker at the jazz club Minton's in Harlem. Parker seemed to befriend him before leading him to a Harlem tenement, taking his last US$17 (Dh62) to buy heroin and leaving the young Jones crying outside in the rain.

In the Sixties it was Sinatra who dubbed him "Q". In fact in America, where racist Jim Crow laws meant Sinatra and his new friend were obliged to move in different circles, the Chairman of the Board took risks on behalf of Jones.

"When we went to Vegas he hired us bodyguards so that there wouldn't be any trouble from the Mob or other folk who didn't like African Americans in the casinos," Jones says. "I was able to party with 'FS' [Frank Sinatra] and Cary Grant and Orson Welles."

In the Seventies Jones made the bond that has come to define his career. Michael Jackson, already a child star with the Jackson 5 and then the Jacksons, was ready to go solo. He asked Jones to produce his first solo album and despite huge record company resistance over Jones being too "jazzy" he prevailed. Jackson's solo debut, Off the Wall, established him as a mainstream adult pop star. Three years later, Thriller, a hybrid of image, dance and song that anticipated the video age, became the biggest-selling pop album ever.

But in a way it's a wonder Jones and the young Jackson bonded. Jackson might have sounded far too poppy for the streetwise former gangster. Jackson couldn't bear to describe music as "funky" because he said it sounded rude. He preferred "smelly jelly" and earned the nickname "Smelly," which stuck for the rest of their friendship.

Surely Q, the veteran of Sinatra and Fitzgerald, doesn't actually still listen to Thriller?

"I hear it," he says. "I have to hear it. From Shanghai to Soweto and Rio it's there all the time. But the music I play at home is usually things like the Mystery Voices of Bulgaria, Richard Bona from Cameroon, Gilberto Gil and Caeteno Veloso, Miles Davis, Gil Evans and some of my things."

Does he miss the King of Pop nearly two years after Jackson's death?

"It is choking to go back and touch those songs again," Jones says. "So many artists reach new levels of greatness as they get older. Who's to say Michael wouldn't have? I don't think we will see anyone like him again."

Jones writes of his days working in the recording studio with such icons as Basie, Duke Ellington, Fitzgerald, Sinatra and Jackson, among many others, in his book Q on Producing, projected as the first in a three-volume series.

It is Jones's seminal work with Jackson that helped make global pop colour-blind, which in turn has perhaps obscured some of the struggles of black music. In the US Jones is lobbying for the creation of a culture secretary post in the federal government so that a younger generation dulled by the constant assault of television/mobile/internet can be steered through the country's great cultural journey.

"Where does our music come from?" he asks. "From Cameroon, from South Africa... Culturally kids today have the attention span of a wet cornflake. They don't know how we got here and they don't know where we are going. It's crazy."

Establishing a US culture secretary would be just one way of telling America's cultural story. Luckily Jones is friends with the president, Barack Obama, whom he met through his friend Oprah Winfrey in 2005. But the friendship between the two black men from Chicago is not as cosy as you might imagine. Obama and his wife, Michelle, sat in Jones's kitchen while he explained why he would be backing arch-rival Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination.

"The Clintons are family to me," Jones says. "I lived in the White House when Bill was in charge. You don't forget that."

Moving in exalted circles can be difficult. Recently Jones found himself embroiled in the Naomi Campbell blood diamonds scandal. He appears in the now infamous 1997 photo with Campbell and Nelson Mandela alongside the suspected Liberian war criminal and former president Charles Taylor. Campbell was questioned last year about the receipt of diamonds at Taylor's trial. Jones looks weary at the first mention of it.

"I was with Naomi two weeks ago and she knows nothing about it," he says. "Nobody knows what the hell that's all about. It's been blown out of all proportion by the media. They'd much rather speak on that or Paris Hilton rather than what is happening in Sudan or Chile. You think I'm going to say 'Yes, Charles Taylor was a bad man'? There's nothing to talk about. We all know it."

Jones has some advice for anyone who gets bogged down in gossip and scandal rather than rising to life's challenges. And he says it's especially worth listening to because "Frank" gave it to him and it has served him well all these decades:

"Love. Laugh. Live. Give. Live each day as though it was your last. And then one day... you'll be right."

Q: Soul Bossa Nostra and Q on Producing are widely available.

The Jones file

BORN Quincy Delightt Jones Jr, March 14, 1933, Chicago

SCHOOLING Berklee College of Music, Boston, Massachusetts. His admission application is in a display case at the school as he is considered to be the most famous alumnus. He dropped out when he received an offer to go on the road with the band leader Lionel Hamilton.

FAMILY Jones has been married three times and has seven children.

FIRST JOB In his early teens, Jones joined a combo with his friend Ray Charles playing in clubs and at weddings.

WORST JOB After a tour with his band Free and Easy broke down because of financial problems, Jones went to work in New York for Mercury Records, rising to vice president. However, he told Billboard magazine: "I was behind a desk every day. Awful! I had to be in there at 9 o'clock, and you had to wear these Italian suits. You had to fill out expense reports and all that kind of stuff. That really made my skin crawl."

HERO Pablo Picasso, who was his neighbour when he was living in France: "Picasso's my man. Picasso's my model. Didn't moan, didn't groan, just kept waltzing and wailing and sharpening his chops, even in his nineties," he told Rolling Stone magazine in 1984.

FAMILY FIRST Jones gathers all his ex-wives, ex-girlfriends and children for Thanksgiving and Christmas. He values relationships and family ties.

QUIRKY FACT He underwent operations to repair two aneurysms in his brain in 1974, and was not expected to survive. As Rolling Stone reported, Jones's closest friends surrounded his hospital bed after the final operation, intending to pay their last respects. Gradually, the stricken patient raised his arm and gave them an obscene gesture. "If y'all think I'm cutting out," he murmured, "forget it." He now has a metal plate in his head and has set off metal detectors at airports.

LATEST HONOUR Last month Jones was among eight new recipients of the National Medal of Arts awarded at the White House by the US president, Barack Obama. The medal honours contributions to the "excellence, growth, support and availability of the arts".

Star power

Among the hundreds of performers Quincy Jones has collaborated with:

Cannonball Adderley

Akon

Louis Armstrong

Charles Aznavour

Count Basie

Art Blakey

Mary J Blige

Nadia Boulanger

Jacques Brel

Clifford Brown

Tevin Campbell

Ray Charles

Nat "King" Cole

Miles Davis

Céline Dion

Snoop Dogg

Tommy Dorsey

Billy Eckstine

Duke Ellington

Art Farmer

Ella Fitzgerald

Aretha Franklin

Jamie Foxx

Dizzy Gillespie

Lesley Gore

Lionel Hampton

Herbie Hancock

Billie Holiday

Jennifer Hudson

Ice-T

James Ingram

Michael Jackson

Gene Krupa

Peggy Lee

LL Cool J

Ludacris

Charles Mingus

Thelonious Monk

Naturally 7

Charlie Parker

Lionel Richie

Rufus & Chaka Khan

Paul Simon

Valerie Simpson

Frank Sinatra

Barbra Streisand

Tyrese

Usher

Sarah Vaughan

Dinah Washington

Andy Williams

BeBe Winans

Amy Winehouse