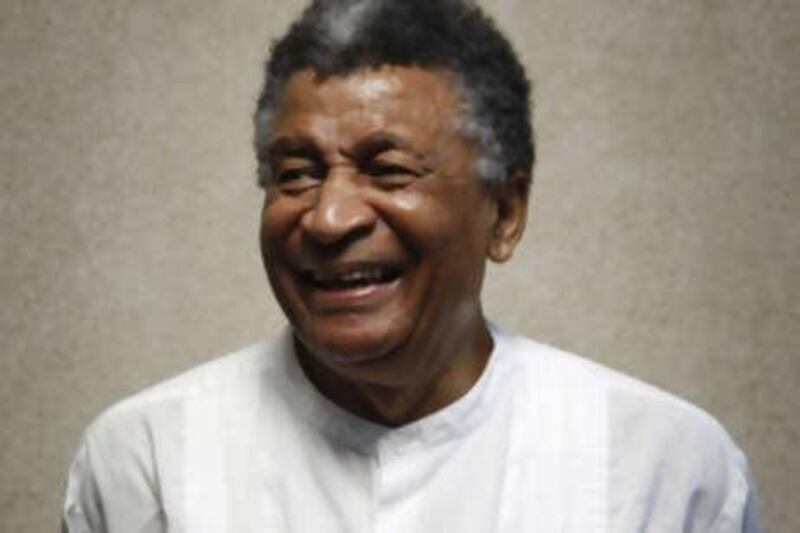

It would not have been surprising if Abdullah Ibrahim had become a bitter and angry old man. Thirty years of exile from South Africa because of his devotion to the art of jazz music must have been hard to bear. Now, at 74 years old, he wants to pass what he has learnt on to the next generation.

The jazz musician, once known as Dollar Brand, composed Mannenberg, which became the anthem of the resistance movement against the apartheid regime. He is driven by the need to fill in what he sees as gaps in the knowledge of todays young musicians about their roots and why their particular brand of jazz sounds like it does. Its why Ibrahim spends so much time in schools and colleges talking to young music students like those he met recently in Abu Dhabi. He wants them to feel the music, not just play it. He talks about music as a holistic process that takes in body, soul and all the references to the past.

For example, he says, "Art Tatum is an incredible piano player. He would walk in and people would say 'God is in the house'. He wrote a piece called Elegy and one day he went to a bar where a young man was playing his tune. Tatum didn't even listen. He said: 'He knows what I play but he doesn't know why I play.'" Ibrahim's reasons for playing are so closely bound to the history of his country that they are inseparable from it. His distinctive style of composition carries echoes of the African landscape along with the sorrows and pain caused by apartheid and the yearning for freedom. His work became a symbol of defiance that led to him being harried by the regime and fleeing the country.

"We always felt there was a large chunk of our collective memory that was being erased because the timeline had been severed. Young people think everything started yesterday. So we thought it was our duty to try and salvage some of this and pass it on," he says. With quiet dignity and often with a surprising sense of humour, he speaks of his early life playing for local gangsters and how he could have quite easily become one of them had it not been for music and his conversion to Islam, which, along with his deep interest in the martial arts and in eastern philosophy, has sustained him throughout his life.

He was born in 1934 in one of the most dangerous ghettos in Cape Town and baptised Adolph Johannes Brand. Dollar was a nickname he picked up in the 1940s when he bought swing records from GIs passing through the seaport. Local youth culture was all about alcohol and drug addiction, and many of his friends either died or were murdered by local thugs. Music is what saved him, he says. "I had a little trio and we were playing to gangsters. The only arenas for jazz were clubs. Thats why its associated with these people. They had this wonderful collection and they invited us to listen to them every Sunday afternoon because we couldn't afford to buy records or have a record player. You had to put on special gloves to touch them. They once said to me that if anybody ever gave me any trouble I should tell them and they would send their panel beaters. I never did."

He chuckles at the memories of those days and how he devised a strategy for keeping the tough guys calm and well-behaved. "In the townships like Soweto, we played the concert and then they took the chairs out and you'd play for the dance. You'd get all these sharply dressed gangsters in the front row and you could hear their comments coming. The last hour of the show had to be so excellent and pleasing, otherwise they demanded their money back. So I wrote a song called Kalahari and wed play it at the end.

"After about four shows they came backstage packing guns. One of them asked what the song was called and when I said, 'Kalahari' he turned to his friend and said I told you. Ive been to all his shows and when he plays this it makes me thirsty." Like many of Ibrahim's compositions, Kalahari evoked images of the African landscape and the man became thirsty as the music transported him into the baking desert sun.

Ibrahim was brought up by his grandparents and believed for many years that his mother was his sister. When he was in his twenties, he discovered that his father was murdered in a racist attack when Ibrahim was four. His grandmother was one of the founders of the local Methodist church, but even as a young man he felt an alienation from that form of religion because of the apartheid system. He converted to Islam at the age of 27. He describes the lead-up to that with more amused chuckles.

"In Cape Town we lived in an society with Muslims and Christians. People intermarried and many of my friends were Muslim. We would know when it was Ramadan and get in some nice food and they would come to us to celebrate Christmas." What he could never come to terms with under apartheid was not being permitted to worship in any church. "How do you resolve this contradiction? I believe in God but I cant go into a church?

"I knew the local iman all my life. When I finally went to him, he said 'I have been waiting for you.' Then came the teaching and then the understanding that I could worship God." Initially, he wanted to be a doctor but because of his race he was refused entry to both medical school and music college. So he began playing and singing with swing bands, developing his own distinctive style. At the same time, he started learning martial arts, partly in order to defend himself.

As the bebop rhythms of the 1950s began to energise a new generation, the young Dollar Brand was at the forefront of the Cape Town jazz scene, giving the beat an African twist. He teamed up with influential musicians such as the trombonist Jonas Gwangwa and Kippie Moeketsi, the saxophonist known as the father of South African jazz. Their music was seen as a challenge by the regime, as it was adopted by the African National Congress. District Six, where they played, attracted the thinkers, writers and musicians of the day, and was seen as a hotbed of sedition. The musicians were constantly watched and harried until many left the country, including the late singer Miriam Makeba and the trumpeter Hugh Masekela. As his group, the Jazz Epistles, fell apart, Ibrahim began to concentrate on solo piano. Along the way he met and married Sathima Benjamin, a singer. They have a son, Tsakwe, now a pianist and guitarist in Cape Town, and a daughter, Tsidi, a rapper known as Jean Grae, in New York.

After the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the regime introduced draconian measures affecting musicians. There were daily arrests, mixed race bands were banned, and blacks were forbidden to play in white nightclubs. Curfews and rules making permits to travel compulsory effectively killed the jazz scene. The Ibrahims decided to leave. They went first to Zurich and later to New York, where Duke Ellington became their friend and mentor, and Ibrahims career as a jazz pianist bloomed.

"We left South Africa, and then we went back again and tried to make it work but the regime monitored us. For me, the finality was that knock on the door at 4am. They came, surrounded my house, kicked down the door, put an automatic weapon to my head and handcuffed me. I asked them what was the charge. They said it was a moving traffic violation, a speeding ticket." That time, Ibrahim was lucky. The police captain turned out to be a fan and told him not to worry about the fine. Two months later, it happened again and this time the captain was not there.

"They took me to a police station. I was there overnight and had to appear the next morning in court in front of the magistrates. My lawyers managed to get me out of it. Two days later, I left South Africa. That was 1976. And then the record Mannenberg took off and became the theme song of the revolution." The emotional scars he suffered during that period have not disappeared, and it pains him that the youth of today know so little about it. Its why he has become what he describes as a "reluctant teacher". He speaks of the job with a kind of weary resignation.

"I lived in exile for 30 years. They took away our citizenship, which meant that we could not return. Exile is not something I would wish on my worst enemy. The most terrifying experience when you are in exile is that you dream you are at home with your family having a wonderful time. Then you wake up to reality. "What worries me today is that everywhere theres violent behaviour. My martial arts teacher has written a book about this. He said people dont use the word senzo, which means 'ancestor', any more. Senzo is also the title of my latest CD and it was the name of my father. All this is gone. The young don't have a base. Its a throwaway culture."

Ibrahim returned to Cape Town soon after Nelson Mandela's release from prison in February 1990, and played at Mandela's presidential inauguration four years later. After a successfully treated prostate cancer scare, he became vegetarian. He is also an eighth dan black belt in the ancient martial arts technique of yakima. He sees a connection with that and music, and every other aspect of life. "When you get your black belt, it's like getting your drivers licence and then you start making progress. After a while, you don't even consider the grading. What matters is how well you perform the technique. Its the same with music. The only thing you are really concerned with is perfecting your art. Its all about discipline. Music isn't an end, its a means to an end. It just gives you a formula that you can work at and you can apply and the same formula everywhere else in your life. The formula is actually to reach unattainable perfection."

Ibrahim and a group of friends have created a project called M7 in an attempt to create a forum in which knowledge from all kinds of disciplines can be shared and adapted. "I have practitioners from all over the world, homeopaths, people who practise traditional Chinese medicines, orthopaedic surgeons and paediatricians. They all come to the concerts and we become friends, and then we start chatting about things. We have a lot of synergy. The seven Ms stand for music, movement, medicine, meditation, martial arts, menu and masters in all the disciplines. We must find some synergy in how they can move this forward."

They have been given some farmland in the Kalahari and hope to bring young people to the area to learn traditional arts of the bushmen and talk about the history of the country and of jazz music. Ibrahim says he doesnt feel like and elder statesman of jazz and says his work is only just beginning. "I don't have a political message. I just play the music to the best of my ability. Once you play the notes theres nothing you can do about it."

@email:pkennedy@thenational.ae