The past decade has been a golden era for Filipino pop music, aka Pinoy-pop or P-pop. The past couple of years alone have marked some landmark moments for the genre, which is rapidly gaining an international presence to rival that of its J-pop and K-pop forebears that have so heavily influenced the music in its current form.

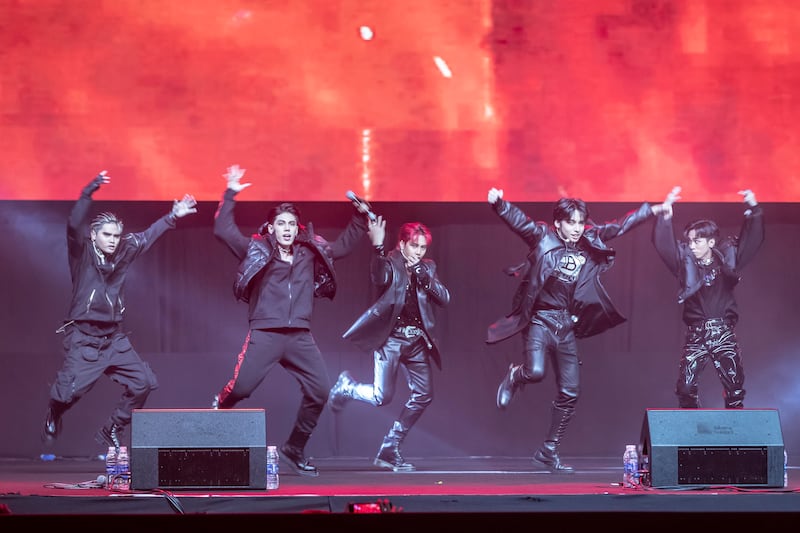

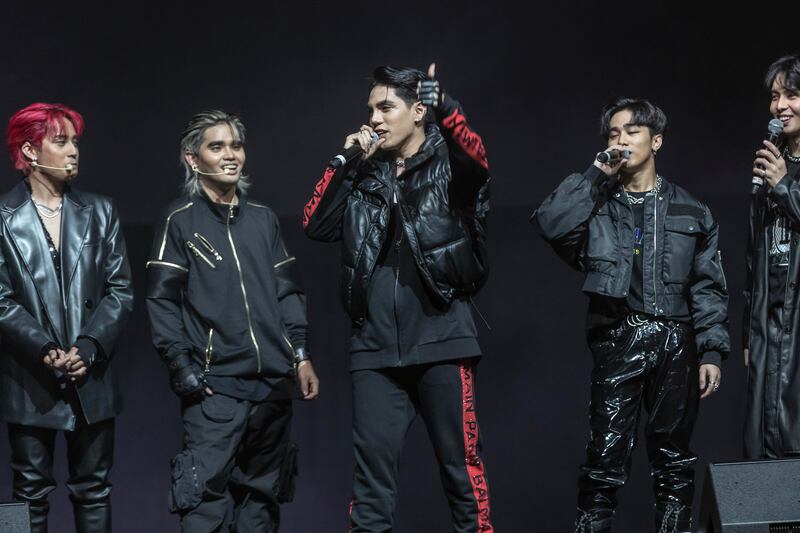

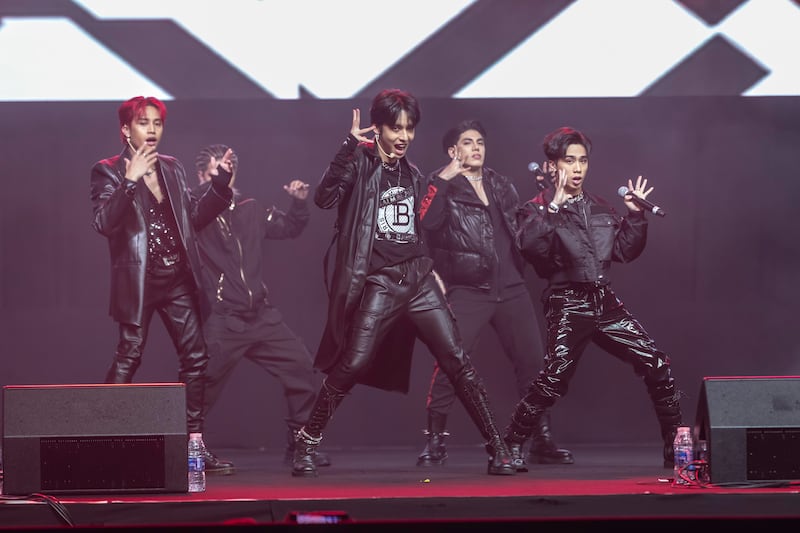

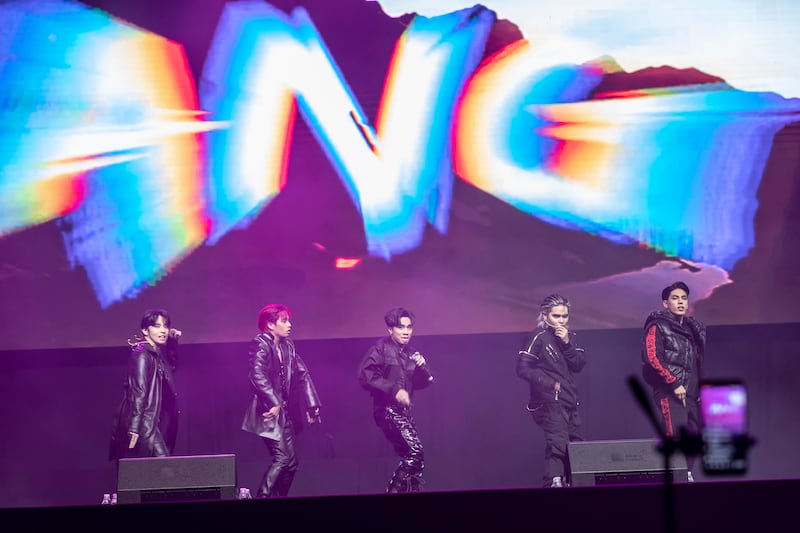

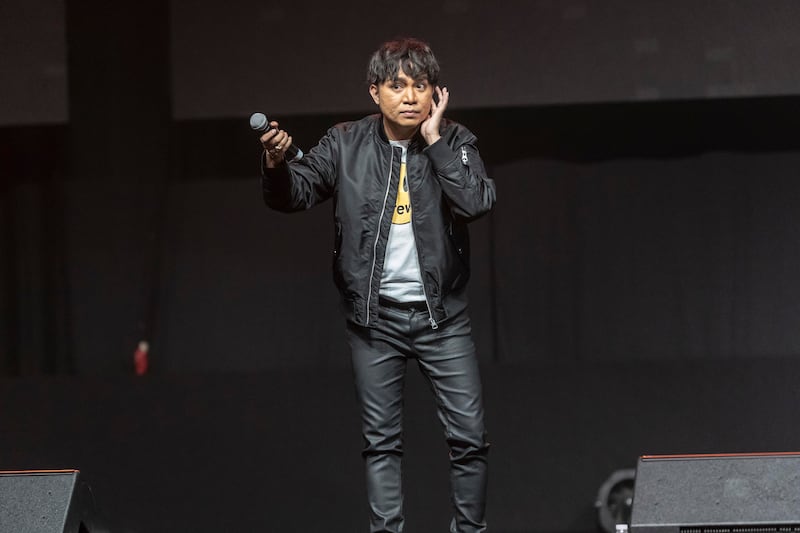

Last year, boy band SB19 picked up a nomination for an MTV Europe Music Award and became the first South-East Asian act to be nominated for a Billboard Top Social Artist Award. They kept this success going into 2022 by spending seven weeks at the top of Billboard’s Hot Trending Songs chart, breaking K-pop superstars BTS’s record for Butter in the process.

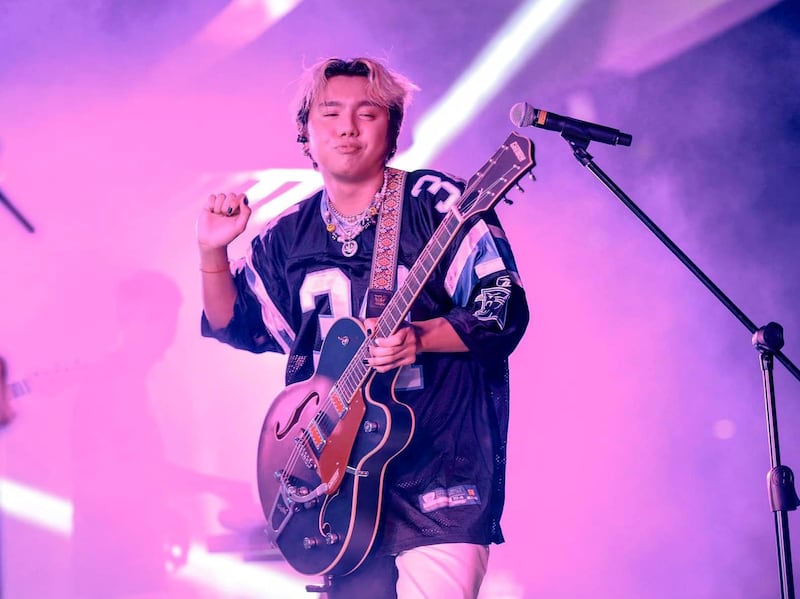

On Spotify’s annual streaming charts last year, Zack Tabudlo topped the Philippines’ most-streamed-song list with Binibini. It’s not entirely unusual for Filipino artists to make the list, but it’s more commonly dominated by international names such as Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande. With Olivia Rodrigues and Bruno Mars — both artists of Filipino descent — joining him in the top 5, and 84 million streams in a single year for Binibini, it was a particularly strong performance.

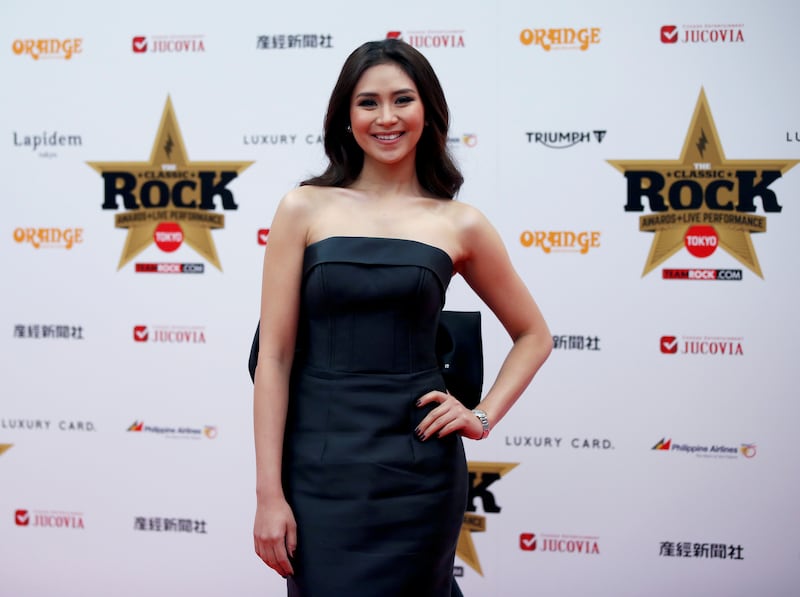

Meanwhile, girl band MNL48 are part of a pan-Asian pop franchise success story, originating in Japan, that is taking the continent, and world, by storm. The Filipina branch of the ‘reality pop’ 48 phenomenon have picked up awards at the MYX Awards, P-Pop Awards and TikTok Awards, and even have their very own theatre to hold performances at Manila’s Eton Centris Mall.

A recurring theme in these success stories has been the heavy influence of K-pop and J-pop, but it wasn’t always thus. While modern P-pop is marked by meticulous dance routines, polished production and squeaky-clean teen pin-ups, the early history of the genre is one of subversion.

The term “Pinoy” began to be widely used as a prefix to domestic pop music in the late 1970s and applied initially to a largely folk rock-inspired movement, sung not in English as had been the norm in the former US colony, but in Tagalog or “Taglish”, and with a frequent undercurrent of opposition to the authoritarian regime of then president Ferdinand Marcos. Heber Bartolome’s 1977 song Nena, for example, told the story of a young girl forced into prostitution owing to an uncaring government, while Florante De Leon’s Digoman (War) flatly states: “I am ready to do battle for the cause of our freedom.”

Craig Lockard’s Dance of Life, a 1998 study of South-East Asian pop music, explained: “The rise of politicised pop music is linked to the development in the early ‘70s of the musical style known as ‘Pinoy’. Sung not in English but in Tagalog [or] slang-filled Tagalog that appealed to urban youth, Pinoy music was a conscious attempt to create a Filipino national and popular culture.”

The term Pinoy-pop really hit the mainstream in 1978 when Freddie Aguilar’s single Anak (Child) sold 100,000 copies in the Philippines in its first two weeks of release — something that was unheard of at the time. The song was released in more than 50 countries and translated into nearly 30 languages, according to local media.

Anak wasn’t an overtly political song. It was a touching tale of a father-son relationship. Aguilar’s 1979 follow-up, Bayan Ko (My Country), pulled no such punches, with lyrics that translate as, “The Philippines, Nest of tears and poverty, My aspiration, See you perfectly free.” This song would go on to become the anthem of the 1986 uprising against Marcos, with Aguilar himself leading the crowds in singing on occasions.

As the 1970s became the 1980s, the growing influence of US hip-hop began to show. Musically, P-pop retained a strong folk influence, in part owing to the lack of easy access to hip-hop standards such as cheap samplers and record decks in the contemporary Philippines. The lyrical poetry of the genre began to emerge in P-pop, however. A trend even emerged among street theatre/musical collectives for adapting the poems of Amado Hernadez — a Marxist Filipino poet who died in 1970 — to music.

It was also around this time that Marcos became interested in the burgeoning Pinoy-pop scene. One might have expected him to want to shut down the growing subculture, but it seems he wasn’t paying too much attention to the lyrics. Instead, impressed by proudly nationalistic song titles such as My Country and I Am Filipino, performed in the native language, Marcos decided this was exactly the sort of movement he should co-opt for political purposes, mandating under a 1978 update to Order 75-31 of the Broadcast Media Council that all Filipino radio stations should play at least three Pinoy songs an hour as part of his campaign to boost the profile of Filipino culture and reduce outside influences.

It wasn’t the first, or last, time a populist leader had misappropriated pop music for their own ends. Earlier this month, British pop group M-People were furious when Liz Truss used their hit Movin’ on Up while she walked on stage for her Conservative Party Conference speech as UK Prime Minister, though they were also happy to note the irony of Truss using a song about breaking up with a deadbeat partner, including the line “pack your bags and get out” to highlight the bright future ahead under her leadership.

It’s a world away from the shiny P-pop product of 2022, but pop music and politics alike tend to move in circles. Filipino politics has already done so this year, with the Marcos family back in power following the election of Marcos’s son Ferdinand Marcos Jr, known as BongBong, as president in July.

Last week, meanwhile, Filipino Senator Jinggoy Estrada suggested banning K-drama and other foreign-made content from Filipino screens in a familiar-sounding call for the advancement of domestic culture.

In March, during the election campaign, Filipina songstress Nica Del Rosario, who has previously written songs for the likes of Sarah Geronimo and Barbie Almalbis, hit the No 1 and 2 spots on the Filipino iTunes download charts simultaneously, with Rosas and Kay Leni Tayo. Both were protest songs urging listeners to reject a return for the Marcos clan and vote for rival Leni Robredo.

Could P-pop be going full circle, too?

Scroll through the gallery below to see SB19 performing at Expo 2020 Dubai