When the winner of this year's Man Booker Prize is announced on October 6, at the usual shimmering London Guildhall ceremony, there's a good chance that the chosen author won't be there to receive the most prestigious award in Commonwealth writing. That's because the three-to-one favourite to take the prize this year - with his new novel, Summertime - is the reclusive and revered South African giant of contemporary fiction, JM Coetzee.

Coetzee is one of only two novelists to have won the Booker twice (the other is the Australian author Peter Carey), and he didn't attend on either occasion. Over a career spanning more than 30 years, he has granted only a handful of interviews - "being interviewed is a kind of torture", he said in one - and avoided almost every opportunity to appear in public that his huge success has afforded him. Even when Coetzee spoke in front of the Swedish Academy in 2003 to mark his acceptance of the Nobel Prize in Literature, he eschewed the customary lecture on his life and work in favour of a cryptic, allusive short story called He and His Man, narrated by Robinson Crusoe.

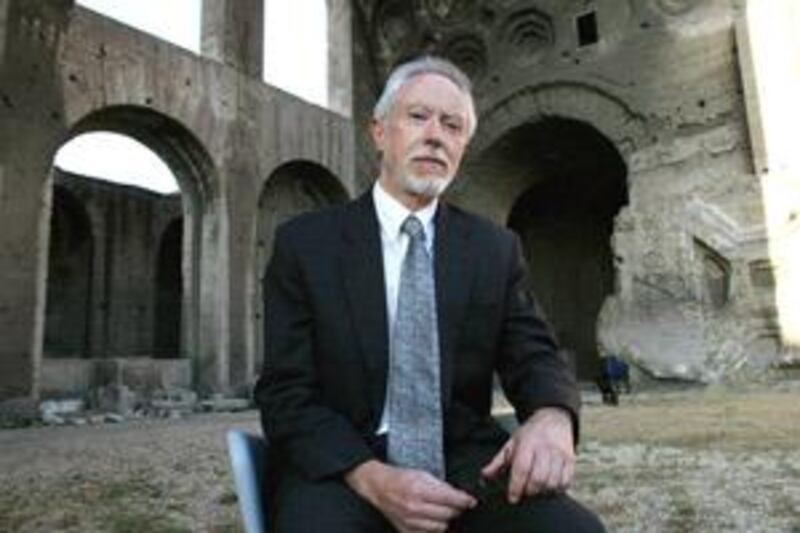

The few glimpses we have of the 69-year-old writer have done little to assuage the literary world's curiosity. Friends and academic colleagues - Coetzee has spent most of his adult life teaching at universities in the US and South Africa - talk of a man who can sit through an entire dinner party without saying a word; a socially awkward, austere character who nevertheless nurses a fierce determination to mine the deepest parts of the human spirit in his fiction. Universally regarded as one of the most important writers of our age, his work is reviled by some in his home country. Coetzee's most famous novel, Disgrace, sparked a scandal in South Africa upon publication in 1999, when then-President Tabo Mbeki denounced it as racist; three years later Coetzee left South Africa for good.

So just who is JM Coetzee? Why does this internationally lauded writer eschew the attention of so many devoted admirers? And what can we learn from him about the strange, alchemic relationship between great writers and their work? It is, at least, an apposite time to ask such questions. While a new Coetzee novel is always a literary event, Summertime has generated even more attention than usual. That's because this book marks the completion of the "fictionalised memoir" series that also includes 1997's Boyhood - about Coetzee's childhood in Cape Town - and 2002's Youth.

The picture of a young Coetzee that emerges from the pages of Summertime is familiar. The novel covers the period between 1972 and 1977, when Coetzee, in his early 30s, returned to South Africa to scrape a living as an English tutor, and, as the jacket blurb has it, "find his feet as a writer". But - even more so than its two predecessors - Summertime is far from straightforward autobiography. The novel is set at some future time after Coetzee's death, and presents us with a series of interviews between Coetzee's biographer, Vincent, and characters who passed through the author's life at the time. "He was a little man, an unimportant man," says one interviewee.

But can the popular conception of Coetzee - as an austere, even cold obsessive - really be the truth? Professor Homi Bhabha, of Harvard University, is widely considered the godfather of academic postcolonial theory; no surprise, then, that he has a deep interest in Coetzee's depictions of post-apartheid South Africa. But the pair are also friends, having met in the early 1990s at the University of Queensland in Australia.

"What makes Coetzee such an important writer is the way he deals so acutely with the contemporary world," says Bhabha. "Coetzee is interested in individual lives and societies caught up in moments of transition. He deals with issues of huge importance; still, other writers do that. So what makes him a contemporary classic? It's partly the innate spareness in his writing; there is no unnecessary glitter, or verbosity, or pretentiousness; he has a major stylistic gift."

But what of Coetzee the man? "I've never found the stereotype to be true. From the first time he came to dinner with my wife and me, the conversation was wonderful. "Yes, he does have an austere persona. He doesn't believe much in small talk. He's not a backslapping type of companion, but at the same time he's a very generous friend." Did he speak of a conscious desire to remain unknown to the public?

"I was aware of his definite desire to keep celebrity at arm's length. It's not a pose on his part: he wanted to be left alone to write and teach. The rest, I think, he views as a distraction from what is important." But if Coetzee has cultivated a sense of self-imposed exile from the world, there are clues to its origins in his early life. He was born John Michael Coetzee in Cape Town on February 9, 1940, the son of rural, progressive, Anglicised Afrikaner parents who distanced themselves from Afrikaner culture and opposed the Nationalist Party's policies of racial segregation. Coetzee later wrote of his childhood, in Boyhood, as a time of "teeth gritting and enduring", as he struggled with a deep sense of alienation from his Afrikaner peers.

After a mathematics degree at Cape Town University, and a brief, unhappy stint in London - recorded in Youth - by 1972 Coetzee was back in Cape Town and teaching in the literature department of that city's university. In 1974 his first novel, Dusklands - which deals with the arrival of Dutch settlers in South Africa - was published. Finally, Coetzee had arrived. But it was the Booker-winning Life and Times of Michael K, published in 1983, that brought international fame. Meanwhile, though, at home the beginnings of a storm that would break years later were already perceptible. Michael K presented a South Africa torn by civil war, through which a harelipped, outcast gardener must travel to reach the birthplace of his mother. But while many outside South Africa lauded Coetzee's take on his country, some at home criticised him for failing to become as politically engaged in the anti-apartheid struggle as fellow writers such as Nadime Gordimer and Alan Paton.

That latent tension erupted monumentally in 1999, around the publication of Disgrace. The book cemented his reputation when it won him a second Booker, but its unflinching exploration of racial tensions in the "new South Africa" prompted accusations of racism; dynamite in a country just years after the end of apartheid. Criticism came from the highest level. In a vitriolic denunciation, South Africa's ruling ANC said Coetzee had "represented as brutally as he can the white person's perception of the post-apartheid black man"; many fellow writers were no less forgiving: "In the novel Disgrace there is not one black person who is a real human being," said Gordimer.

Shaun de Waal is one of South Africa's leading cultural critics, and was literary editor of the Mail & Guardian at the time: "There was a knee-jerk reaction by the ANC against Disgrace, and it became a scandal. Hyper-sensitivity to any perceived racism was a trait of President Mbeki. "The newspapers seized the story, and one in particular ran a long, unflattering profile that accused Coetzee of being an unpleasant man, involved in various recriminations with colleagues.

"South Africa is such an unliterary country, and Disgrace was misread in some quarters. It's far too complex a novel to be labelled 'racist'. It deals with issues that are of the upmost importance in the 'new South Africa', and it is prescribed in schools. It's certainly entered the public consciousness." Coetzee remained silent throughout. But rumours persist that he was so badly stung by the affair that it was the primary factor in his decision to emigrate to Adelaide, Australia, in 2002, where he has lived since.

There are other reasons, though, why Coetzee might legitimately yearn for a fresh start. In 1989, his son, Nicholas, fell from a balcony and died; around this time his ex-wife, Phillipa Juber - the pair married in 1963 and divorced in 1980 - died of cancer. Coetzee has said he was drawn by the "beauty" and "spirit" of Australia. Certainly the move has given rise to a late blossoming of his extraordinary creativity, with four full-length novels since 2003.

Intriguingly, this late Coetzee is more preoccupied than ever with making fiction from his own life, with the relationship between a writer and his work. There are even rumours that he is collaborating with a biographer. Could it be that this most elusive of literary giants wants, finally, to reveal himself? "This deep interest in what it means to bring the self into writing has always been part of Coetzee's work," says Carrol Clarkson, an academic at Cape Town University and a leading Coetzee specialist. "We find him probing these issues even more closely in the most recent novels: the central character in Diary of a Bad Year, for example, is an ageing novelist called JC, living in Australia.

"These works are fiction, but at the same time Coetzee is asking: is all writing necessarily autobiographical? Is it ever possible to tell the whole truth about oneself?" There can, it seems, be no simple answers about Coetzee. Even as we approach him he slips away from us, into a hall of mirrors of his own making. Perhaps we must come to accept, then, that the many attempts to look beyond Coetzee's writing to the man himself are misguided, that the most authentic Coetzee available to us is the one revealed ironically, hesitantly, and obliquely in his novels.

After all, how much must we know about Coetzee before we can be said to know him? How much, Coetzee seems to ask us, do we really know about anyone? A brief glimpse of Coetzee's take on the matter can be found in a documentary interview conducted in 2000, in Cape Town. Here, Coetzee stands on a windswept Diaz beach, looking out to the ocean, and tries to describe what writing means to him: "For me it is a necessity to write," he says, "and a necessity of an obscure kind. I don't know why it's a necessity. Perhaps it's better for me if I don't know too much about myself in that respect."