A large circle with a thick border of gunmetal blue is encased in blood-red lines. In places, that blue breaks free and branches out towards the centre, on one side forming jagged spokes, on the other resembling a fat pincer. There is detail within: grid networks; small circles like wax seal stamps. From a distance we seem to be looking at a crude insignia or design, perhaps for a shield or an amulet. Or is it more sophisticated than that – an arcane symbol, a cryptic diagram, a mysterious pictograph?

Up close, and with help of an accompanying caption, we learn that it is a map. Painted with gouache and ink, the ring of blue is in fact ocean. One of the vertical spokes is the Nile and the pincer is an inflated Indian Ocean. The small circles are islands – Cyprus, Crete and Sicily – embossed on the Mediterranean. Africa extends like a giant claw. As Arabic script slides into focus in those tight grids, we note how it marks the many administrative districts of the Islamic empire, including Muslim Spain ("Al Andalus"), the Arabian peninsula and Baghdad, by then the centre of the empire.

Dating back to 1297, this is a Persian copy of a 10th-century world map by the little-known map-maker Muhammad Al Farisi Al Istakhri. Like many Islamic world maps from this period – and in contrast to their Christian counterparts – it is orientated with south at the top, and Arabia is given pride of place at the centre.

It is now on display as part of a fascinating new exhibition in Oxford, UK, called Talking Maps, which displays a wealth of gems from the Bodleian Libraries' collection of more than 1.5 million maps, along with some contemporary works and specially commissioned 3D installations. All have stories to tell about our place in the world – the paths we have taken, the roads we have travelled and the knowledge gleaned along the way.

The variety is impressive. There are “blueprints” of towns and cities, lands and seas, through the ages; war maps, including trench maps and one for the D-Day landings; spiritual maps that direct the faithful to enlightenment and salvation – and the faithless to Dante’s hell; and flights of fancy charting Utopia, Treasure Island and the fantasy realms of C S Lewis and J R R Tolkien. Many are made on paper, but some are on animal skin. Artist Grayson Perry’s satirical map of Brexit Britain is a tapestry inspired in part by Afghan war rugs. A stick chart designed by sailors from the Marshall Islands to navigate their archipelago is constructed from wood, cane, shells and coconut fronds.

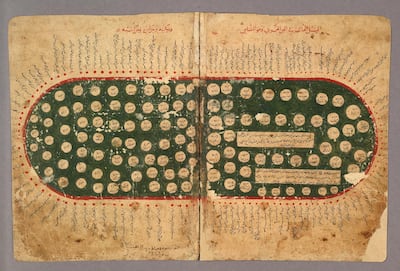

The exhibition's Islamic and Arabic maps stand out both for their singular beauty and for their vital contribution to the history of cartography. A map from the wonderfully named The Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes, an 11th-century cosmographical treatise compiled in Egypt, depicts the Mediterranean as an oval body of water. It appears to have been designed for purposes of trade and navigation, for the sea is studded with 118 islands and fringed with 121 harbours.

Another maritime map, this time from an early 16th-century sailing manual by the Turkish commander Piri Reis, presents an exquisitely hand-drawn island in the Aegean Sea – and hints at Ottoman imperial aspiration.

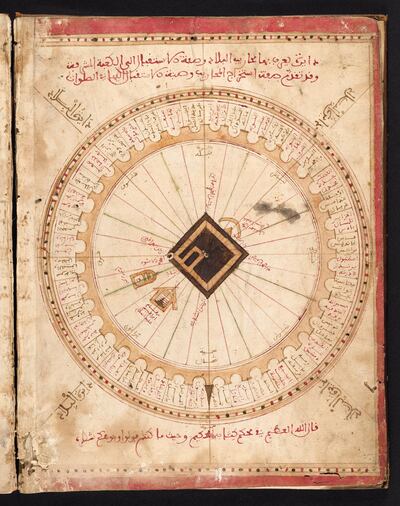

Many visitors will be enthralled by a design from 1571 by the Tunisian scholar Al Sifaqsi. Renaissance historian and co-curator of the exhibition, Jerry Brotton, tells The National it is one of his favourite pieces in the show. "We see this beautiful map of Makkah in great detail – showing the Kaaba and other important sites – while also allowing Muslims across the Mediterranean to orientate themselves in relation to the holy city, depending on where they live. Each mihrab depicts Muslim regions and cities."

However, the main highlights of the exhibition are works based on the groundbreaking achievements of one Islamic geographer. In 1154, Al Sharif Al Idrisi finally completed his Entertainment for he who Longs to Travel the World, a geographical compendium commissioned by King Roger II of Sicily. The book, regarded as one of the greatest works of medieval geography, contains a circular world map and 69 regional ones.

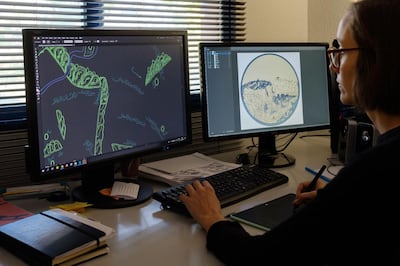

Both are on display – the latter in a new format that halts viewers in their tracks. Those individual regional maps were never intended to be united in Al Idrisi's day. But Factum Arte, an arts workshop in Madrid, took high-resolution scans of each and then digitally stitched them together. The result is a stunning composite that shows how the world looked to an Arab cartographer in the 12th century.

Once again, we see the world upside down. “Many scholars believe south is at the top, as the communities that first converted to Islam lived directly north of Makkah and Madinah, so could orientate themselves on a north-south axis,” Brotton explains. “Maps like this one might seem unfamiliar, especially to a western viewer, but they were completely logical to their viewers and users.”

This piece ranges from China and Korea on one side to the raindrop-like Canary Islands on the other. Africa sprawls across the top half; it was clearly perceived as a vast and mysterious continent. Much of it is rendered blank, signifying unknown and thus uncharted territory. The UK appears in the bottom right-hand corner, with Cornwall jutting out like a lethal talon. Sicily is oversized, perhaps in deference to Al Idrisi's patron. Inevitably, the Middle East is at the heart, with a particularly prominent Yemen.

The other outstanding work on display is a real object of wonder. In his Entertainment, Al Idrisi made mention of another of his world maps – this one more remarkable for being engraved on to a huge silver disc. That disc disappeared, believed lost at sea. Now, centuries later, we can admire a new version of that fabled work from Factum Arte.

"The object we have produced is not really a facsimile," notes Adam Lowe, the founder of Factum Arte. "It's a transformation of the data contained in the Ottoman copy [of the Entertainment] housed now in the Bodleian, which has been rethought in the workshops in Spain and put back on to a silver two-metre-in-diameter disc by a totally international team working with a common goal."

The disc dazzles, literally and figuratively. The craftsmanship involved in the topographical features is extraordinary. Rivers, waves, mountain contours and Arabic place names are intricately embedded. Al Idrisi’s vision of the world is revealed as a finite space of recognised limits and quantified surfaces – but also as a place of glittering possibility, with areas ripe for discovery.

Both these projects – the recreated disc and the pieced-together map – stemmed from, and were steered by, a mutual appreciation of Al Idrisi's work. "I'd been fascinated by Al Idrisi's book and maps for years, alongside my old friend Adam Lowe," Brotton declares. "We always loved the poetic nature of Al Idrisi's book and its title, as well as his blending of different intellectual traditions – Greek, Roman, Christian, Jewish, Arab – with little apparent concern for religion.

“There is of course a certain romance to the story – that silver disc showing the known world, described in such detail but never seen, and subsequently lost after King Roger’s death – and this captured our imagination. But it also allowed us to use new digital technology to cast light on an old medieval map, and there are undoubtedly more examples of where this research can go in future years.”

It is a tantalising prospect. With luck there will be further collaborative projects of this kind. Not only do they help us appreciate or re-evaluate little-known treasures, they show us where we came from and how we got to where we are today.

Talking Maps is exhibited at the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, England, until March 8. More information can be found at www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk