There is at present a remarkable flowering of the Jeddah art scene, a sense that the young and reforming country of Saudi Arabia – having been relatively isolated from the rest of the world – has something new and different to offer on the artistic stage.

Jeddah's yearly arts festival, 21,39, took place last week, and its ancillary events this year stretched across the country. Organisers took international visitors to Dammam, on the country's east coast, to see the gorgeously high-spec Ithra: King Abdullah Aziz Centre for World Culture, the Saudi Aramco-funded art and cultural space that opens later this year, as well as to the King Abdullah Economic City to see the country's first-ever solo show, Drum Roll, Please of Ahmed Mater.

The latter is in itself an incredible development. Mater is widely regarded as the pre-eminent figure in the Saudi art scene, and his photographs have toured to major institutions such as the Brooklyn Museum in New York and the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. But his work, which has been critical of development in Saudi, has lacked visibility in his home country until last weekend, when his photographs, sculptures and videos were installed across an industrial-looking gallery in the still-under-construction King Abdullah Economic City. Not only that, but Mater has been tapped by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman to lead the Misk Art Institute, which will open in Riyadh in 2020.

Mohammed Bin Salman’s encouragement of the entertainment and visual art sector is seen as proof of his modernising and reforming credentials, as well as his commitment to the youth of Saudi Arabia.

Much of the artwork made in Jeddah responds to these reforms with what Mater calls “nervous optimism”, there is excitement about the changes, albeit tinged with a degree of anxiety around the rapidity with which they’ve come and uncertainty about the future. “Artists should know what could also be problematic after the age of restrictions and the oil,” he warns.

Much of the work made in Jeddah is political, and critical of conservative elements of society, but also keen to hold onto facets of Saudi culture that may be fading as a result of some of the new reforms. Most artists are young – born in 1979, for example, Mater is already the scene’s elder statesman – and they often work across different disciplines, such as art, architecture, and graphic and fashion design. And in a scene lacking much museum infrastructure, 21,39 has become an important international event.

In 2013, Mohammed Hafiz, a co-founder of Athr Gallery and the vice chairman of the Saudi Art Council, created 21,39 – the name refers to the lateral and longitudinal coordinates of Jeddah – along with 12 others and under the patronage of HRH Princess Jawaher Bint Majed Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud.

The idea was to establish, Hafiz says, an “independent platform” to support artists in Jeddah and to showcase them to foreign audiences. Unable to find state funding the first year, 37 of the most prestigious (and some of the wealthiest) families of Jeddah stepped into the breach. Since then, the event has morphed into more of a biennial mode, with international curators of increasingly starry stature invited to put together the event’s main show.

Last year, Lebanese/German duo Sam Berdaouil and Till Fellrath paired with young Saudi artists to explore the potential for education, and this year the Tate Modern curator Vassilis Oikonomopoulos addressed – as the show's title, Refusing to Be Still, implies – the feeling of change in the Saudi art world. "OK, we know this is the situation," he said of the cultural climate in Jeddah. "But we must move forward."

It’s surprising how different the Saudi art scene feels to that of the Emirates. This is not simply a question of scale: Jeddah still has only two main galleries, Athr and Hafez, but it would not be a leap to say that Jeddah and Dubai boast roughly the same number of artists. And while Dubai has taken on a global contemporary style, the question of how to balance tradition and contemporaneity is key to Jeddah artists.

Calligraphy and geometric motifs appear in new, revamped ways – not as a de facto choice, but connected to a cognisance that traditional Middle Eastern art forms are an overlooked form of knowledge and aesthetic practice. “I used to think that everything from the West was superior, education-wise,” says Dana Awartani, who trained both at Central St Martins in London and in traditional Islamic illumination. “But when I left London I started reading about Arab history and culture and realised that was not the case.”

She continues: “There was an expectation that as an Arab I would only talk about being a woman or Palestinian exile. That’s not what I can relate to. Especially now that there is such a bad view of Muslims and Arabs, I think it’s important to shed light on the positive, and show the beauty of the culture.”

Awartani works in a studio atop her parents’ comfortable villa, with two dogs who nuzzle – separately, or they bicker – at her feet. After Central St Martins she trained with a master in illumination in Turkey, working towards an “ijazah”, meaning that she would become a master herself. She has the air of someone slightly surprised by how much she knows, and she bends this knowledge of illumination practices to contemporary ends: “I am working with things that have been forgotten.”

For the exhibition The Clocks Are Striking Thirteen, which opened at Athr Gallery during 21,39, Awartani made her most socially engaged work, an installation of traditional Islamic motifs embroidered on panels. These mimicked the screens through which the wife of a 17th century Mughal ruler whispered so she could rule without being seen. A soundtrack throughout the room enlivened the words of female Arab poets from the pre-Islamic period. Installed in lightboxes, the work had an unmistakably contemporary display, but located itself firmly in an Eastern context.

The Clocks Are Striking Thirteen, curated by one of Athr Gallery's former directors, Maya El Khalil, showed works that played with materiality and symbolism in novel ways. And it had feeling: there was a sense of things at stake.

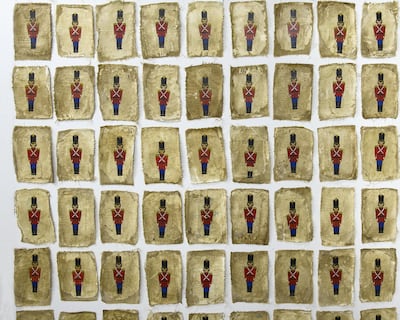

The Egyptian artist Mohamed Monaiseer hand-painted 3,500 English beefeaters on small strips of cloth that he had washed with his own clothes, as if this icon of British imperialism was inextricably saturated with his own being. Zahra Al Ghamdi showed dried, round little cushions of leather, climbing across the floor and up the wall as if they were some form of vegetation or folk practice whose name or genealogy was already forgotten. In other works, Al Ghamdi has examined her grandfather’s traditional house in the south of the country, where she was born, and which now lies abandoned: one work shows the carved wooden doors bound with red rope, as if, she says, the house itself were crying. Though this idea is somewhat literal, the work, like her current installation at Athr and the others in the show, was buoyed by the evocative feel of its material: a sense of organic tactility that rejects the hygienic plastics of modernity.

Maha Nasrallah responded to the loss of life in Syria with an installation of qobqab, a traditional wooden shoe once found throughout Syrian souqs, which she rendered in ceramic and mounted on the wall, as if they are now useless museum items rather than those of daily use. More than that, placed empty in rows, they were a cri de coeur marking those whose feet would once have worn them.

The exhibition of 21,39, Refusing to Be Still, was a mixed success. Pairing mostly young Saudi artists with established international ones, the show suffered from a lack of dialogue among the works: it was unclear how the curatorial leitmotif, the feeling of change in the air, applied to the non-Saudi artists. The three-part video work ARCHERY by the British artist James Richards, for example, could have been a wonderfully provocative choice – Richards' work explores different forms of desire – but these resonances were never developed.

Oikonomopoulos worked extensively with the artists and there were some standout pieces. Ilona Kalnoky's Cube #3 and Cube #4, two beautiful, compact sculptures made of clay fired in the Saudi desert sand – with a strange texture that connected them to many of the works in The Clocks Are Striking Thirteen – suggested both the after-effects of some violent process, and a softened, welcoming result. Moath Alofi's aerial video Mihlaiel stunned for its views on a region that time forgot – and that tourism has, unbelievably, yet to discover. The work shows the important Islamic site of Khaybar, a once-complex citadel that now lies in ruins.

This idea of recouping what’s being lost amounts to almost a form of activism, connected to communal memory. In another series of works, Alofi documented the doors and random scrawls of graffiti that are disappearing from his native city of Medina. “Each door I collected tells me a story,” he says. “These doors are being demolished because of the expansion of the Holy Mosque. The doors represent the identity of the building and the people behind them. Some of these graffiti are the expression of the people – a memory, a line, a joke, maybe a drawing by the children.”

____________________

Read more:

Jeddah’s art scene takes shape under its own terms

Changing Saudi art scene: New arts complex to open in Jeddah

Your guide to Dubai's Gulf Photo Plus photo week

____________________

A performance of traditional Saudi dancing, staged by Ahaad Alamoudi, questioned the differential between how Saudi is seen by those on the outside, to whom falcons are marketed as a touristic emblem, and from the inside, where they are still part of a living practice. She screenprinted images of falcons onto costumes for a performance of the Sufi-inspired dance of the khabeti. "There are two different narratives: when you're inside the country and when you're outside the country," Alamoudi says. "This comes from me trying to understand my country: the virtual space and the messaging that is generated and produced by my country. I study viral videos and I analyse them in an ethnographic manner.

"The changes are happening so quickly that it's a very exciting time," she continues. "For me it's hard to grasp where I stand... There are girls who are like yes, I want to drive, and there are others who are fearful. The khabeti, the Sufi twirling, all these gestures represent the emotional impact of the changes that are coming."

This year, the government budget was reportedly lower for 21,39 – ironically, I was told, because there are now so many other competing cultural programmes – and few foreign journalists and curators were invited to come. If the general consensus of Saudi is that it’s on the verge of a deluge, this year felt like the pause before international attention floods in. Alongside this, there was also ambivalence: the sense that Saudi artists, while keen to show their work to an international audience, already find enough material in their own terrifically fraught, socially experimental country.

“It’s a very interesting time to be producing work in my country right now,” says Alamoudi. “There is this idea of the future that is very close and very now. We feel it’s coming, and we are just waiting for it to arrive.”