One of the most densely populated cities in the world, Dhaka is choked with traffic: 18 million people across a 300-square-kilometre city, all heading to work and going home at the same time. Cars creep, honking, along the highways, while in a slipstream beside them, brightly coloured rickshaws, enclosed tuktuks, bicycles, people, and dogs jostle past. The sides of buses are dented and scarred with the evidence of many encounters with wing mirrors, like tin toys battered from overuse.

Amid this intensity, the Samdani Art Foundation, run by collectors Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, aims to present a different side of Dhaka: that of a city with a long history of artistic production. The couple founded the biennial Dhaka Art Summit to put the city's art world on the map and to support the Bangladesh scene.

Every two years, they host a 10-day programme of exhibitions, talks and workshops, at the four-storey Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy in the city centre (the couple are now building a bespoke arts institution north-east of Dhaka).

Now in its fourth exposition, the Dhaka Art Summit has become a staple on the power circuit of the art world, drawing in the likes of Glenn Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern, whose attendance was described by one guest as akin to a state visit.

“When we started the foundation in 2011,” says Rajeeb Samdani, “A lot of people were talking about South Asia, especially the western world, but we thought the definition of South Asian art was wrong. Most of the time South Asian meant India and Pakistan, but there are six other countries, which includes us.

“We also thought that Bangladesh doesn’t have a contemporary art museum, and we wanted to build a South Asian collection for our future generations. When we started doing that, we realised we have no clue about our region. Within the region, we are not talking. So we created a platform for South Asia.”

The gambit worked and the first event attracted about 50 international visitors, rising to 200 the next year and 800 after that. This year, 1,200 flew in (many hosted by the Foundation). As for local visitors, the last event attracted 138,000 to the exhibitions.

The Foundation has now expanded the event from four days to 10, to accommodate the rising number of visitors.

“I’ve never been in any other place where the general public and the ‘who’s who’ of the art world have the same chance to engage with the artworks on their own terms,” says Diana Campbell Betancourt, chief curator of Dhaka Art Summit. “It’s a very inclusive space. We have rickshaw drivers in here, tea-sellers in here.”

Even for an art world accustomed to event culture – where the performances, talks and networking opportunities around a biennial's opening can be as big a draw as the exhibitions – this is an event of surprising variety. With its programme of workshops, talks, films, performances, a forum for artist-led initiatives, and 12 exhibitions of contemporary and archival work running simultaneously, the Dhaka Art Summit feels like a year's worth of museum programming compressed into 10 days.

One of the major goals of this year’s programme, Betancourt says, is to re-examine the links between Bangladesh and South Asia. “We want to think about Bangladesh away from India,” she says. “Thailand is closer to Bangladesh than Delhi or Mumbai are, Yangon is closer, an hour-and-a-half away. Migrant workers are flowing that way, but intellectuals and so-called culture are not.”

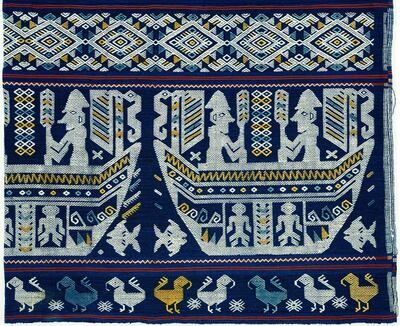

Betancourt co-curated a series of exhibitions, Bearing Points, with curators Abhijan Gupta and Ruxmini Reckvana Q. Many of the works point to textiles as both a traditional art and a scar of colonialism – local textile production was decimated under the British Empire and now remains in a cheapened form of sweatshop labour.

Thai artist Jakkai Siributr, in the installation The Outlaw's Flag (2017), addresses the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar. Exploring the way that national borders cut across the lands of ethnic minorities, he made woven flags for made-up countries from material sourced from the beaches of Sittwe, Myanmar, and Ranong in Thailand, the departure and landing points for many Rohingya migrants.

A standout exhibition is Planetary Planning, curated by Dr Devika Singh, which looks at the relationship between abstraction and modernism in architecture in a South Asian context, with works by artists such as Lala Rukh and Seher Shah, and plans by the Bangladeshi architect Muzharul Islam. The circle appears here as a motif, both of the exhibition display and within the works themselves: arranged so that the viewer walks through the show in a circle.

It opens with Zarina Hashmi's The Ten Thousand Things III (2016), an installation of woodblock prints based on letters which the UK-based artist's Pakistani sister would write to her, all arranged in large circular vitrine. Amie Siegel shows a looped video of amateurish paintings showing the evolution of dinosaurs, filmed in a museum in Chandigarh, also arranged around a circular room.

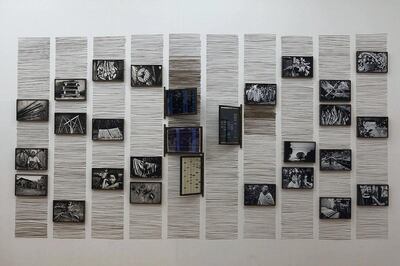

Elsewhere, archival displays show the results of ongoing research into the region's history. Vali Mahlouji, who organises the curatorial platform Final Decade, exhibits press and video documentation, and photographs from the Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis, a revolutionary multi-disciplinary performance festival that was held in Iran from 1967 to 1977, when it was banned by religious decree.

Betancourt curates an archival display of the Asian Art Biennale, the artist-run biennial in Dhaka that has been the driving force for Bangladeshi art from the 1980s onwards, and which laid the groundwork for the arts scene the Samdani Art Foundation is taking forward.

Meanwhile in the talks programme, curators discuss widening the canon in order to make room for non-western artists. The latent tensions of the event – the disjunction between an art world elite and a poorer Asian host city – are here discussed in terms of museum practice.

Lowry from MoMA and Morris from the Tate Modern made frank remarks on their panel about the ways in which established museums are trying to fill out the geographic gaps in the art histories they collect, as well as in the larger context of the pressure for acquisitions.

On another panel, Zoe Butt, one of the three curators of next year’s Sharjah Biennial and director of The Factory Contemporary Arts Centre in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, spoke about how to build institutional infrastructures in developing art regions – a question pertinent to those in the UAE, where the museum-building project has not just been acquisitions and material construction, but the immaterial work of preparing and creating an art ecology of producers, mediators, and audiences.

How to sustainably grow an arts scene is also a question for Dhaka itself. Aaron Cezar, director of the London-based Delfina Foundation, advises against thinking that the Dhaka Art Summit is the only move in the Samdani Art Foundation’s playbook.

“We are just a thin slice of the project. It’s an incredible initiative to develop infrastructure for the arts for a place already intellectually charged, but lacking global connections,” he says. “Workshops throughout the year have a big effect on art practice. The infrastructure is in nurturing new generations of artists.”

_______________

Read more:

NYUAD exhibition shows life from a migrants' perspective

Serge Attukwei Clottey shows Dubai how he disrupts the art trade

Changing Saudi art scene: New arts complex to open in Jeddah

_______________

Cezar this year selected this year's winner of the Samdani Art Award, Mizanur Rahman Chowdhury. In addition to the summit and the foundation, the Samdanis – whose wealth comes from the Golden Harvest Group, a diversified food conglomerate of which Rajeeb Samdani is the managing director – are both on the South Asia Acquisitions Committee and the Tate International Council, which helps the museum to acquire works from the region, as well as being members of the Arts Advisory Council at Harvard University's South Asia Institute. They support local programmes that go on after the razzmatazz of the Dhaka Art Summit moves on, such as the Samdani Artist-Led Initiatives Forum (which occupies stalls in the top floor of the building), as well as research and workshops.

The couple plan to open the Srihatta – Samdani Art Centre and Sculpture Park, the first major contemporary art institution in Bangladesh, later this year, in a tea-growing region of Sylhet, 250km north-east of Dhaka. The sprawling site will feature space for artists’ residencies, a sculpture park, and galleries for curated shows from the couple’s collection of more than 2,000 works of South Asian modern and contemporary art. “Two years down the line,” Rajeeb Samdani tells me, “we’ll sit together and talk in Sylhet.”

Dhaka Art Summit runs until Saturday. Visit www.dhakaartsummit.org