Born in 1947, a year before the establishment of Israel, veteran Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour never imagined he would witness another Nakba.

The emotional impact of events in Gaza over the past two months or so has been deep and profound. He has many artist friends in Gaza who have lost everything – their artwork, their homes – but who are at least alive. For now.

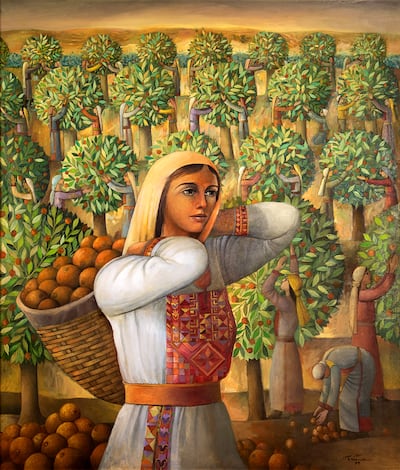

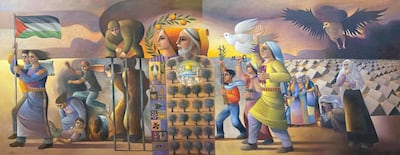

He has completed several paintings that he started before October 7 in addition to a mud work, he tells The National by phone from his Ramallah studio. His oeuvre of “realistic, symbolic” artwork, spanning five decades, is characterised by figures and landscapes that embody and celebrate Palestinian cultural identity, the land and “sumud”, or steadfastness. But they also reflect its history of loss, displacement and exile.

Seventy-five years of painful history, punctuated by one tragedy after another, has created a kind of emotional and mental “rust”, says Mansour, and he has used art to eradicate that accumulation. Doing so has involved a layered process in the production of his artwork.

“I’d think about something and then I’d make sketches,” he explains. “I’d then prepare and enlarge it on the canvas and start working on the colours, and so on.”

Processing the crisis

With the crisis in Gaza unfolding, his artistic approach is taking an unanticipated turn. He has begun a new, large piece for an exhibition.

“All the images that come to my mind are really horrible,” he says. “Some I can't get out of my mind – I can only get them out through painting. You know, I always hated abstract expressionism. I didn't like it. But I think now is the time for it.”

This latest period has demanded a more immediate, visceral approach. He explains: “This kind of art that I'm [creating] now, I don’t make any sketches. I start immediately, directly, on the canvas, with colours and brushstrokes, and the colours are dripping. There’s a different kind of artistic solution for everything and it reflects the problem you are dealing with.”

Paintbrush mightier than the sword?

Sliman has been at the forefront of Palestinian art for decades and has played a leading role in shaping Palestinian visual cultural identity as events have unfolded.

In 1973 he co-founded the League of Palestinian Artists. In 1987 he and three other artists established the New Visions Movement in response to the First Intifada, a movement that boycotted Israeli supplies and turned to local materials, like mud and henna, which could be utilised both practically and symbolically to produce powerful art.

One wonders if today the impact and influence of political art, such as Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, has been supplanted by the grisly imagery and utter destruction – in this case of the crisis in Gaza – that is being captured by ubiquitous camera phones and transmitted almost instantaneously around the world on social media.

Sliman believes art has the power to “change feelings, but not much [beyond that]. It can’t shape the course of history. Money can maybe, but not art.”

Brush with mortality

He is grateful to remain artistically active, however, after suffering a stroke two years ago which impacted his ability to continue his calling.

“I’m able to paint still, but less productively,” he says. “I have problems focusing, and my art needs a lot of concentration. It now takes a little time for me to finish one painting. I have many physical problems with moving around a painting. My left hand, I cannot use. It’s becoming better but it's still a problem.”

Maintaining a daily routine remains therapeutic, both mentally and physically. “I try to work daily, to go to the studio, to do something there – not painting all the time, but maybe reading or making sketches or something like that. I try to go everyday. It's a routine and I don’t like to stop it.”

Closer to home – and Palestinian art’s home

When Mansour spoke to The National five years ago, he was critical of the newly-established Palestinian Museum in Bir Zeit, where he was born, saying at the time that it lacked direction and vision. Following the recent announcement that Palestinian artist Amer Shomali has been appointed its newest director general, Sliman sees a better horizon for Palestine’s flagship art and cultural institution, believing that having an artist in the role will be beneficial for it as a gallery space for Palestinian art.

“I think Amer is very good for the role,” Mansour says. “He is really sincere, a wonderful artist and a good planner as well. He has an eye for art and he believes in the importance of art. He's a good choice. I think Amer will run it in a different way, but of course he needs money to do it [well] and, as we all know, money for art is always very scarce.”

Seeing the positive in the negative

Returning to the present, Mansour feels that, while the war has been devastating, the horizon does not remain entirely dark. He perceives a growing shift in the public’s attitude in the West in a way that could benefit Palestinians. Sympathy for the plight of his people has increased greatly due to widely visible updates on the ground from both journalists and civilians about recent events, as well as a renewed interest in Palestinian culture that has buoyed book sales documenting the situation's long history.

In an interview two years ago, Mansour joked that he was born one year before the Nakba and would probably die one year before Palestinians achieved their freedom. While that goal seems distant now, Mansour now hopes for a unified state that brings people of all backgrounds together in peace.

“I’m sure it will be one state, sooner or later, because it's such a tiny place. Jerusalem Ramallah, and West Bank – all are important for Jews and us too. Same with Ramle, Yaffa, Haifa and Acco, they are very important for us and a big part of our [shared] history.

“People will never forget these places, so in the end when we learn how to live with each other, side by side, maybe they will decide to live in one state. That's my nice dream. But I'm sure it will be like this because people can't live in ghettos – mental or physical ghettos.”