Yusuf Bakti, a Syrian merchant living in the Italian port city of Liverno, picked up his quill pen and began to write again.

He had already dealt with the consignment he was sending to a friend and fellow trader in Alexandria, but had something else that was bothering him.

His nephew, sent from Egypt to learn the business in the Tuscan city, was proving troublesome, distracted by the pleasures of Italian life.

“What we see is that his heart is passionate, and the arrogance and self-conceit are in his blood,” Bakti wrote in Arabic script to his old friend in Egypt.

The problem, the Syrian wrote, was that boy’s mother was Egyptian. "The arrogance and self-conceit are in his blood.”

The boy, Bakti admitted, had “exhausted” him.

“We find that his case is hopeless…My efforts are worthless. The Egyptian descendants have no worth.”

The letter never arrived. Accompanying Bakti's goods, it was loaded on a Tuscan trader, the St Luigi di Gonzaga. In early January 1759, the merchant ship set sail for Alexandria on what should have been a short and uncomplicated voyage.

Just a few days later, an ominous set of sails appeared on the horizon. It was the British frigate HMS Ambuscade, bristling with 40 cannon. The Italian ship had no choice but to surrender. The cargo was taken as a prize, to be sold and the profits divided among her officers and crew.

Bakti’s post and around 80 other letters from fellow traders in Arabic were glanced at and disregarded as unintelligible by the British. Yet somehow they survived, intact, first in the bowels of the British Admiralty storerooms and then in the UK National Archives in London.

Now they are being read for the first time in 250 years, the seals cracked, and the paper unfolded. Long after Bakri and his nephew faded from history, his complaint is being heard.

Reading them for the first time “was a bit like finding Tutankhamun’s tomb,” says Dr Miriam Wagner. “I felt quite special opening them.”

Dr Wagner is director of research at the Woolf Institute, founded in 1998 to create an academic framework for discussing religious differences and based in Cambridge.

For this project, she is working with a young Egyptian postdoctorate researcher, Mohamed Ahmed, with the aim of translating and studying the collection of letters and eventually publishing them, with a commentary, in two books.

The letters are part of a much larger collection known as the 'Prize Papers', a colossal haul of around 160,000 letters found on thousands of ships seized by the British Royal Navy or privateers - essentially government licensed pirates - over three centuries.

Stored in the UK they are now being digitalised in a project by the National Archives and the University of Oldenburg in Germany.

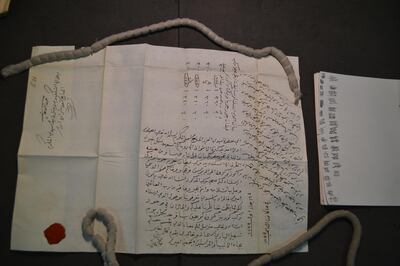

The Arabic prize papers, though, are separate, although they may form part of the final digital archive. The script, even for skilled linguists like Dr Wagner and Dr Ahmed, is filled with anachronistic words long lost, and are sometimes partly in a Latin-based code to protect trade secrets.

In the longer letters, the handwriting frequently deteriorates as the writer tires. Sometimes it can take hours to agree on a single word.

“There are words that even as a native speaker I do not understand,” says Dr Ahmed. “They are not even in dictionaries.”

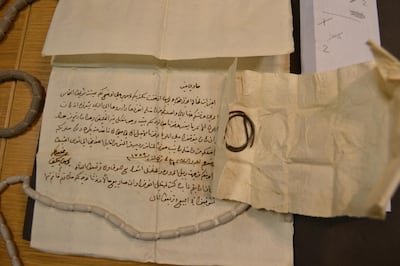

The letters, though, are in perfect condition.

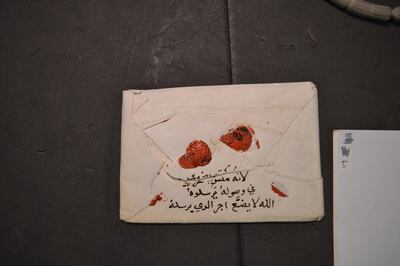

“The ink shines,” says Dr Ahmed. Removed from the archives, conservators gently cracked the wax seals and unfolded them after 259 years in the dark.

They were in three large bundles, each addressed to the traders’ main agent. Inside the bundles were dozens of letters, to other merchants, to be distributed by local courier networks.

The senders were Christian Arab businessmen, but the men they did business with were from many faiths, including Muslims and Jews. Some of the phrases are Christian or Hebrew but they are written in the international language of trade in the region, under the Ottoman Empire, which was Arabic.

“It’s a snapshot of the old Middle East with its incredible multiculturalism,” says Dr Wagner. “This whole idea of one nation, one faith, one language is a very European concept that then penetrated the Middle East. These letters came before the time when this kind of thinking began poisoning things.”

The Arab merchants’ goods and correspondence had become entangled in a global conflict known today as the Seven Years War.

Waged across continents and oceans, it pitched the European powers against each other in two great coalitions, one that was headed by Britain and Prussia, and other including France and the Holy Roman Empire, centred in Austria but whose lands included much of what is now Holland.

The Arab merchants were doubly unfortunate. Firstly the St Luigi di Gonzaga was chartered by a Dutch owned company and suspected of carrying French cargo, drawing it into the conflict. Secondly, the year 1759 saw Britain's Royal Navy inflict a series of crushing defeats on its enemies, becoming the most powerful in the world.

For HMS Ambuscade, soon to take part in a the victory over the French fleet at Lagos, the Tuscan merchant ship was easy pickings. Records show the cargo of the St Luigi di Gonzaga was a snapshot of global trade in the mid-18th Century.

There was wool from England, safflower, olive oil and a case of wine. From the Dutch spice islands in the east, there was coffee and pepper. Even more extraordinary was a consignment of cochineal, a red dye produced by crushing insects found only in Mexico, then a Spanish colony.

On its return voyage, the ship would have carried leather, from camels, bulls and buffalo, one of Egypt’s main exports. There was a request for Egyptian mouse traps, apparently particularly effective in dealing with the many rats on the ship.

The letters include precise instructions about when to sell the goods to maximise profits. There is intelligence passed on that a caravan is due to arrive from Hejaz, the coastal region of today’s Saudi Arabia, which will first drive prices up but potentially flood the market.

The caravan is presumably carrying frankincense, much in demand in Europe, but there is a warning that it might not be of good quality, mixed with stones and dirt.

Away from trade, the human stories emerge. Some worry about the damage caused by the same conflict that led to the capture of the Tuscan ship.

“Concerning the war between the English and the French, may God bring peace for the merchants and for the citizens. Rather, the war goes on, and there is inflation in this city and in Marseille and in Spanish territories. All of this is due to this war.”

The Christian merchants show proper sensitivity in addressing their Muslim counterparts. To his Muslim partner in Alexandria, Haji Sa’d Sarara, the Christian Anton Kayr writes: “God glorified and exalted be he may bring all the wellness in the name of all the prophets and messengers, Amen”.

Some of the letters are from Catholic clergy in Rome, sending letters to their brothers in Middle East monasteries.

Ben Gabriel al-Kildānīn expresses sorrow over the deaths of his mother and other family members in the course of a year.

“What should I do, should I cry, what should I say or write. O sorrow.

“Do I not deserve to stay beside my mother and brothers, so that I could smell their scent, and to please myself by looking at them. How can I live without them, I should have gone to the grave before them.”

It is the Syrian Bakti who emerges as the biggest personality, so much so that he has become the central character and inspiration for Livorno, an Arabic historical novel written by Dr Ahmed and recently published with support from Sharjah's 1001 Titles initiative.

In his letter, the Syrian reports than an operation to remove a kidney stone on a younger relative has been a success and that he is sending the stone “in a purse for our brother Boutros so you can see it.

“We are prohibiting him from eating blood-thickening foods, such as cheese, fish and salted meat because of the fear of that the blood thickens and the stone comes back for a second time", Bakti adds.

But it is the behaviour of the wayward nephew that continues to preoccupy him, with the young man now subject to a curfew.

“He can only take leave when I know where is he going and with whom, according to the mandatory rules. But this did not work with him, because of his arrogance and lack of humility.”

Did the youth ever mend his ways? Sadly, the records do not tell.