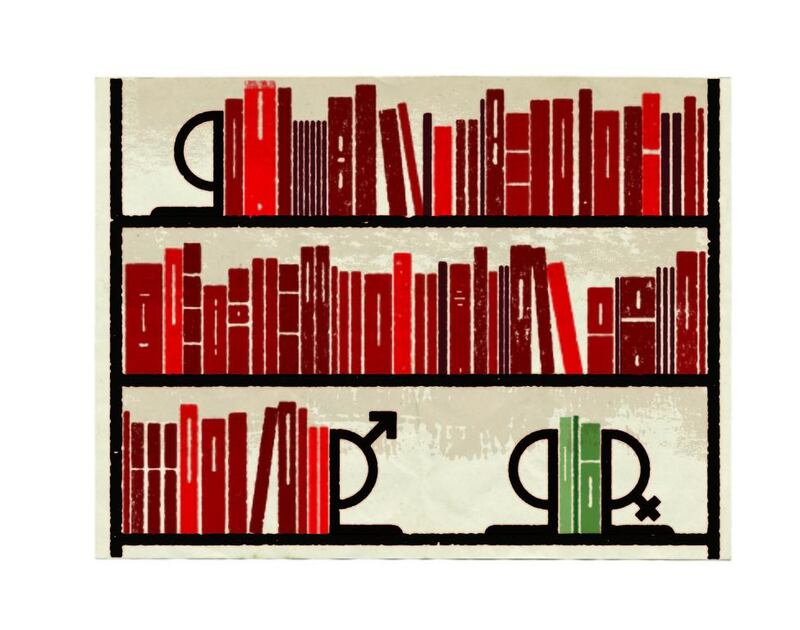

In the past year, US- and UK-based translators have plunged into a discussion of gender inequality in literary translation. According to the Three Percent project, which tracks translations in the United States, approximately 70 per cent of books recently brought into English were by men. Last week in London, the Free Word Centre hosted an event called Few Women in the History: Tackling Imbalances in International Literature.

But when it comes to works translated from Arabic, there is a feeling among many male writers that the situation is the opposite: that women’s works are over-represented in English. In 2009, Lebanese poet Youssef Al Bazzi wrote cuttingly in the journal Banipal: “We can state here that there is not a single Arab woman writer, regardless of the quality of her literary writing, who has not met with European deference, translation or presence.”

Al Bazzi’s sweeping statement aside, there are strong criticisms to be made of the western project to rescue Arab women. As Lila Abu-Lughod writes in Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, there is an antifeminist literary subgenre that depicts Arab and Muslim women as objects needing western salvation.

This complicates matters, but bibliodiversity still matters. Yes, many readers would like to concentrate on the “best” that’s out there, even if it’s all written by heterosexual men in one block of Beirut’s Hamra Street. Yet those writers need the rest of us. Literary ecosystems, like other ecosystems, thrive on crossing borders, genres and perspectives.

Jordanian short-story writer Hisham Bustani suggested last month that, compared to what’s published in Arabic, Arab women’s writing may be more present in translation. He added that, since no statistics are kept on book production by gender, it’s impossible to say.

Indeed, reliable numbers are few. This year, the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) released stats on how many women’s books were submitted for the prize: 26 per cent of the total. The Katara Prize, meanwhile, said 28 per cent of their submissions were by women. This is not so different from the proportion of Arab women’s works in English translation. Last year, Three Percent logged five of 20 Arabic translations by women. In 2014, the ArabLit count was seven of 40.

Oddly, IPAF-listed authors are not well-represented here. In its short history, about 20 per cent of IPAF-longlisted authors have been women. Of the 24 books by women, just two have appeared in English. IPAF co-winner Raja Alem’s The Dove’s Necklace will soon make a third.

But do IPAF, the Katara and other big Arabic-novel prizes do a good job of reading and celebrating women’s writing?

Since its emergence in 2008, the IPAF has been criticised both for suppressing and for supporting books by women. Egyptian academic Samia Mehrez, who for many years headed up the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature, said in 2010 that the prize was underrepresenting women. The next year, IPAF touted near-gender-parity on its longlist and was criticised for unfairly boosting women’s books.

In 2014, just two women’s works found their way onto the 16-book longlist. Judges that year said they had evaluated novels on pure literary qualities, adding that gender should never be a factor. Jordanian poet Siwar Manassat was not convinced.

But what if all the women’s books were dreadful? As with the English Man Booker, IPAF doesn’t release a full list of contenders. So the judges’ failure to list Hanan Al Shaykh’s Virgins of Londonistan, Duna Ghali’s Orbits of Loneliness, Mansoura Ezz Eldin’s On Emerald Mountain, Lina Hoyan El Hassan’s Nazek Khanum or Radwa Ashour’s The Woman from Tantoura might mean those books simply were not submitted. It’s also worth noting that male judges have been in the majority every year.

Certainly, gender imbalance isn’t an issue affecting only Arabic literary prizes.

France’s top literary honour, the Prix Goncourt, has gone to a woman just 11 of the 102 times it’s been awarded. And several graphic novelists, including Riad Sattouf, boycotted this year’s Angoulême Festival Grand Prix because no women appeared on the longlist. The 2015 CairoComix awards, by contrast, had more female winners than men.

Alex Zucker, co-chair of the PEN America Translation Committee, has observed that anthologies tend to be more gender-balanced. This is certainly true of recent anthologies of Arab and Arabic literature in translation: Beirut Noir, edited by Lebanese novelist Iman Humaydan, slightly favours female authors. Equality was the publisher’s requirement, Humaydan said, but including work by authors like Najwa Bakarat, Bana Baydoun, and Hyam Yared could not have been a hardship.

The Book of Gaza: A City in Short Fiction, edited by Palestinian novelist Atef Abu Saif, is also nearly balanced between male and female authors. The collection lays emphasis on younger Palestinian writers like Mona Abu Sharekh, Najlaa Ataallah, Yusra al Khatib and Asmaa Al Ghul, giving us a broad view of recent literary innovations.

At the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature, which wraps up today, director Isobel Abulhuol says that gender balance has been achieved without any conscious focus.

Balance is important “inasmuch as we want to represent as wide a range of authors and illustrators as we are able to”. But, she added, an author’s gender plays no role in the selection process.

Since its director is a woman, the festival may suffer from an unconscious egalitarianism. Also, a growing proportion of Emirati authors and publishers are women. Abulhol said: “In terms of Arabic literature in particular, of the 34 Emirati authors attending in 2016, 19 are women and 15 are men, while of the 23 authors from the rest of the Arabic-speaking world, 15 are women and eight are men. Of the total 159 authors signed up at the time of writing, 86 are male and 73 female.”

Among US and UK translators, there’s talk of funding a prize for women’s books in translation, much like the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction. However, there is also disagreement about whether a women-only prize helps support women’s writing or, as British novelist A S Byatt has suggested, ghettoises and trivialises it.

In any case, we can surely agree that a wide variety of women’s voices benefits all of literature, bringing with it new approaches to content and form. Just as translation feeds us new ideas, so does a broader spectrum of women’s writing: from a range of countries, backgrounds and social classes.

And what about the “too many” or “too few” Arab women in translation? Western publishers should certainly run, not walk, away from the toxic “saving Muslim women” narrative. And it’s always a good time to be leery of cultural interventionism. Furthermore, anyone who does what Al Bazzi suggests – promoting books that aren’t interesting or well-written – serves no one.

However, the success of Beirut Noir and The Book of Gaza shows that gender parity isn’t impossible and that there’s no reason to shrink from a broadly egalitarian approach.

M Lynx Qualey is an editor and book critic with a focus on Arabic literature and translation issues. She edits the website arablit.org