CAIRO // Hussein Salem is often pilloried as a man who used his friendship with the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak to amass billions of dollars.

Starting in a government job paying 18 Egyptian pounds (Dh10) a month, Mr Salem rose to become one of Egypt's most powerful men, dubbed the "Father of Sharm El Sheikh" for his role in developing a cluster of villages along the Red Sea into a glitzy resort.

Corruption investigators say his success was due, at least in part, to his ties with the former first family.

But Egyptian prosecutors are in talks with his lawyers on a deal that would see all charges against him dropped if he hands over a share of his assets to the government, both sides say.

Mr Salem, 79, who fled during the uprising of early 2011 that eventually ousted Mubarak, is accused of money laundering, enabling others to make financial gains and hurting national interest. He is under house arrest in Spain, facing other laundering charges there.

The negotiations involving one of the Mubarak era's most controversial and reviled figures represents a change for the government of the president, Mohammed Morsi.

It is among the first signs that its zeal to recover hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of dollars of allegedly ill-gotten wealth by Mubarak, his family and his inner circle may be flagging amid the country's worsening economic situation and mounting difficulties in locating the funds.

The decision in January to start negotiations with Mr Salem and other members of Mubarak's inner circle is vehemently opposed by government investigators, whose job is to follow their money trails through labryinths of offshore bank accounts and companies.

While some prosecutors favour a financial settlement, the investigators say no deal with Mr Salem should be considered until the full extent of his wealth and its location is determined.

They also say such deals condone corruption and prevent greater recoveries in the future.

"It is a mistake," said Mohamed Mahsoub, who resigned as minister of state for parliamentary affairs in December, saying the government refused his calls to make investigations into Mubarak-era corruption a higher priority.

"What kind of message does this send to businessmen and officials? To me it says, 'don't worry about corruption. If you get caught, you can just negotiate later and give up some of your assets'."

Late last year, Mr Mahsoub called for an independent committee of judges, anti-corruption activists and financial experts to lead Egypt's search for assets of the Mubarak-era officials and business figures.

In part, he said, he was trying to wrest control from an "ineffective" judicial panel created by the military after Mubarak's resignation to oversee asset recoveries.

But Mr Morsi rejected his recommendations in December without giving a reason, Mr Mahsoub said.

The next month, the head of the Public Funds Prosecution - one of a half-dozen agencies carrying out corruption investigations - said the government was ready to negotiate with members of the old regime, including those who had been convicted of embezzlement and corruption.

"The reason they are doing this is they are very frustrated with the process of recovering the assets," said Hussein Hassan, an anti-corruption expert in the Cairo office of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, who works with the Egyptian government.

"The process is very long and the amount of money they have recovered up till now is very small. Reconciliation could mean money brought back to Egypt very fast."

Saleh bin Bakr Al Tayyar, a Saudi lawyer based in Paris to whom Mr Salem has given power of attorney to negotiate a settlement with Egypt, said Egyptian authorities were "taking the case very seriously".

Mr Al Tayyar said Mr Salem's assets were in the "low billions" of dollars. An independent auditor is still completing a valuation of the assets.

Any agreement with the Egyptian government, he said, would involve the forfeiture of about half of these assets.

It is unclear whether any agreement between Mr Salem and Egyptian authorities would require an acknowledgement of guilt by the billionaire that he acquired some of his fortune illegally.

Mr Al Tayyar said his client denied all charges. But Mr Salem "is a very old man, in his late 70s, and he would like to leave no burden behind for his children and his grandchildren.

"He is buying his tranquillity."

Government investigators and anti-corruption activists caution that Mr Salem's serenity might be bought too cheaply. They insist no deal should be brokered until a full accounting of his assets is completed.

"Maybe he'll give up half of his known assets now but we'll find out later that he had much more," said Mr Mahsoub.

"The negotiations with Salem have angered a lot of people in the government who want to know why they were investigating him if the end goal was a settlement."

US government documents obtained by The National back up those worries, showing that after fleeing Egypt in 2011, Mr Salem began liquidating his holdings and selling assets in opaque transactions that shroud ownership in secrecy.

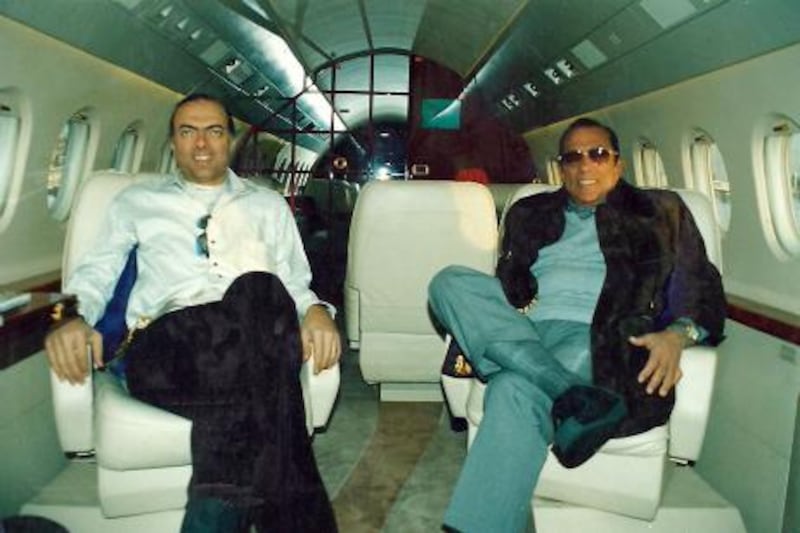

Less than three months after the Egyptian public prosecutor indicted Mubarak, his two sons and Mr Salem on corruption charges in 2011, Mr Salem sold his Falcon 2000EX, a private jet costing more than US$30 million (Dh110.1m), documents filed with the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) show.

The buyer of the plane was Noor Airways, which is owned by the Turkish businessman Ali Evsen. Investigators in Egypt and Spain, where Mr Evsen and Mr Salem are accused of money laundering, have been looking at a host of connections between the two men.

Mr Evsen sold the plane soon after to an undisclosed US buyer, FAA documents show.

Mr Salem has successfully filed cases preventing his extradition to Egypt because he is a Spanish citizen. But Spanish police have accused him and Mr Evsen of money laundering over a transaction there.

The earliest transaction between the men dates to 2008, when Mr Evsen claims he was sold a 28 per cent stake in Eastern Mediterranean Gas (EMG) for an undisclosed sum. The deal was not made public at the time and was only disclosed after the 2011 uprising.

But the Illicit Gains Authority is still trying to verify the details of that transaction, which are hidden in several offshore companies registered in jurisdictions that do not require ownership disclosures.

In 2008, Mr Salem's stake in EMG was held by Mediterranean Gas Pipeline, registered in the British Virgin Islands, which was owned by Clelia Assets, a company registered in Panama, according to Panamanian documents obtained by The National.

After the 2011 uprising, Mr Evsen notified EMG that he was the owner of Mediterranean Gas Pipeline through his company Avalon Adventures, also registered in the British Virgin Islands, a summary prepared by the Illicit Gains Authority shows.

But the detail that has puzzled investigators is that the directorships of Clelia Assets, the original owner of Mediterranean Gas Pipeline, only transferred from Mr Salem's two adult children to two executives of the Evsen Group after Mr Salem's indictment.

His lawyers declined to respond to questions about the transactions. Mr Evsen, through a spokeswoman, also declined to comment about the transactions but said he did nothing wrong in any of his dealings with Mr Salem.

The use of a chain of offshore companies is a frequent strategy for people trying to conceal their assets, said Eric Lewis, a partner at the Washington law firm Lewis Baach, who specialises in asset recoveries.

"Assets that are the product of corruption will almost never be held in the name of an official," Mr Lewis said, not responding specifically to Mr Salem's case. "They are nearly always held through a chain of offshore companies or by a nominee owner."

twitter: For breaking news from the Gulf, the Middle East and around the globe follow The National World. Follow us