The jewels look utterly contemporary: voluptuous curvilinear shapes carved into crystal or chalcedony, set with diamonds; the rough, rounded finish of a huge, 22-carat hammered gold ring; a bracelet string of tumbled rock crystal beads, interspersed with onyx and diamond beads and a giant carved crystal heart. You'd be hard pressed to find pieces this bold on Fifth Avenue, in the Place de la Vendôme or Bond Street.

Yet these were the stars of a Sotheby's sale of the personal collection of the enigmatic mid-20th-century designer and French Resistance heroine Suzanne Belperron, and some were made as far back as the 1930s.

Almost a century later, most of us have never heard of Belperron but for the cognoscenti of the jewellery world she was not only the most important female jeweller but also, arguably, the most important master jeweller of the last 100 years. That is borne out by the results last month at Sotheby's Geneva: every piece sold above the estimate, with some fetching many times their expected price. One rock-crystal and diamond ring - as sleek and modern as anything you might find in London, Paris or New York - sold for $498,255 (Dh1,830,240), more than six times its high estimate of $80,000 (Dh293,865).

Twenty-two of these pieces were bought by Ward and Nico Landrigan, the New York jewellers who relaunched Verdura - the marque of the flamboyant designer Fulco Di Verdura, who worked with everyone from Coco Chanel to Salvador Dali. Now, a former head of jewellery at Sotheby's, Ward Landrigan, and his son Nico, are in the process of doing the same for Belperron. They are currently collecting important pieces for their "museum collection", certificating original pieces using the Belperron archive - the major part of which they bought in 1991 - compiling a long-planned book and hatching a plan to remake her jewels for a new audience.

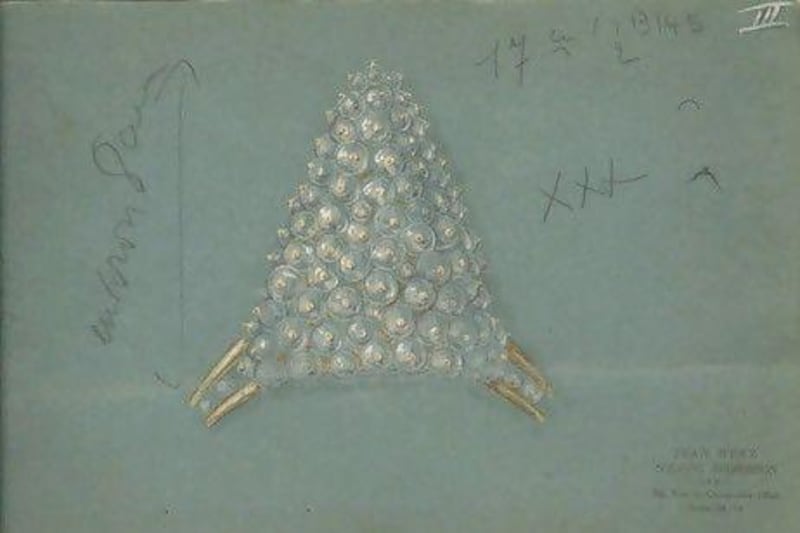

"I'd been shown the archive as a teenager in Paris when I had no interest in going to work in the jewellery business," says Nico, "but even at that point, I felt that these drawings were fascinating. It was modern art in the context of jewellery and stones. They were very compelling to me then, and now that I understand what was going on in the 20th century and how revolutionary what she did was, I'm even more smitten."

He's not the only one: Karl Lagerfeld is a passionate collector of Belperron's jewellery today. He revealed his vast collection of Belperron pins and brooches in the May issue of Architectural Digest, and used the colour of one of her blue chalcedony rings as the starting point for his spring/summer 2012 collection. In her time she was feted by the likes of Jean Cocteau, Colette, Elsa Schiaparelli and Jeanne Lanvin, her jewellery appeared regularly in Vogue shoots of the era, and customers such as the Duchess of Windsor - a woman who really knew her rocks - were devoted to her.

So who was this designer that has people vying to buy her pieces and competing at a most authoritative auction? And why is she not up there in the canon of famous artists and designers of the last century, along with Cartier, Schiaparelli and Verdura?

Born in 1900, the daughter of a merchant in the Jura region of France, an area known for its gem-cutting industry, after studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Besançon she made a rapid, if conventional, ascent in status when she moved to Paris to work for the jeweller René Bevoin, where she stayed through the 1920s, creating pieces in the Art Deco style that was so very of-the-moment.

"She really mastered Deco," says Nico Landrigan. "Her Deco things are, I think, jaw-dropping; they're every bit as avant-garde within that period as what was being done at Cartier and Van Cleef. But she got bored at what everyone else was doing. Yes it was popular, but what could be more boring than everyone agreeing about what's stylish? Hence that curvilinear, abstract, experimental style that came off her brush and pencil."

This distinctive aesthetic became so synonymous with Belperron that when, in 1932, she left Bevoin at the invitation of the gem dealer Bernard Herz to be creative director of Maison Herz, she refused to sign her pieces. With total creative autonomy, she claimed: "My style is my signature," and proceeded to break down the traditions of fine jewellery, throwing together unprecedented combinations of colours, stones and materials noble and humble.

Cuffs exquisitely carved out of semi-precious stone held huge sapphires or coloured diamonds, and casually threaded tumbled emeralds were treated almost as simple glass beads. Like any jeweller today, her inspirations were global - African tribal masks, Chinese stylised clouds and leaves, Ancient Egyptian pyramids, Indian gem carvings, shells, flowers and butterflies - but her sensibility was utterly modern.

"She was very generous, very sensual, and she was not interested in gold or platinum or anything like that," says Olivier Baroin, antique jewellery expert and co-author of a recent book called, simply, Suzanne Belperron. "She just wanted to marry the colours, or put a diamond in wood. She was an excellent colourist. She liked shapes, and she liked colours. She accommodated the jewels with dresses, with haute couture. She was working with people like Nina Ricci and she liked to match the jewel and the dress."

Belperron remains something of a figure of mystery. A noted beauty who always wore black, she received her clients, by appointment only, in her apartment. This enabled her to take into account a customer's character, looks, skin, eyes and hair when designing. For example, she chose blue chalcedony for one of the Duchess of Windsor's most famous parures to match the American's eyes.

Yet she also received the Legion d'Honneur for the part she played in the French Resistance during the Second World War. The conflict resulted in her backer, Herz, being sent to a concentration camp - where he died in 1943 - and his son Jean becoming a prisoner of war. Jean and Belperron resumed their business after the war but she had continued to work with whatever materials she could get hold of throughout the Nazi occupation of Paris.

For enthusiasts of Belperron, there have been few ways to authenticate her output thanks to her refusal to sign her work. But while the Landrigans hold what they had thought was the complete collection of drawings and inventory books, in 2007 Baroin came into possession of Belperron's special-orders archive. Now he too can offer authentication of certain pieces using the fascinating order books from her personal appointments.

"In the archive there are 6,730 clients, and 25,000 appointments, and she was very, very precise," says Baroin. "She wrote down everything, every detail - even if the customer forgot his umbrella, she would write 'Mr X forgot his umbrella'."

Baroin's book, together with Lagerfeld's article and the Sotheby's sale, have created a sense of momentum for the Landrigans' plans to relaunch Belperron, though they have clearly been somewhat discomfited by the speed at which Baroin's book came out.

"It's almost embarrassing but we've been working on [our book] since 1999," says Nico. "We've been photographing private collections for what seems like forever, and the idea of taking so long is that it's serendipity that brings pieces out of safety deposit boxes and from under mattresses."

Relations between the two factions appear polite if slightly strained, Baroin saying of the Landrigans, "I have a lot of respect for Ward and Nico Landrigan; I wish them to make beautiful pieces and to make good business of her name ... But it's not so simple because Madame Belperron was making the jewels with her eyes, her hands, her heart and her sensibility."

Nico Landrigan, meanwhile, says: "I was just thrilled that some of these documents weren't destroyed, because what we had been told was that the other parts of the archives were destroyed; but at the same time frustrated that they weren't reunited with everything else."

While the official Belperron book may still be some time away, Landrigan admits that the first collection has been accelerated because of this new interest.

"Yes, I think we will be speeding it up. I'm not exactly sure when our unveiling of our first collection will be but I will also say that we've been playing around with some of the more difficult lapidary techniques for a couple of years now. I think next year there'll be something you can sink your teeth into. Frankly I can't wait."

Using third and fourth generation jewellers whose families worked with Belperron until she retired in 1974 (she died in 1983, aged 82) is an indication of the quality the company is looking at: this is absolutely not costume jewellery.

"I'm 33 years old and I have friends who appreciate great design, but it's hard to have things accessible to 33-year-olds," says Landrigan. "That said, she did some incredible things in materials like smoky quartz and blue chalcedony. Great things don't have to be in gold and diamonds and rubies and sapphires."

To find out more about the collection and forthcoming sales, see www.belperron.com. Suzanne Belperron by Sylvie Raulet and Olivier Baroin (The Antique Collectors’ Club) costs £75.00. For more information visit www.accpublishinggroup.com or call 01394 389977.