This year didn’t kick off the way I had hoped. When my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, it shifted my optimism for 2024 to a sense of dread for what would come.

With dementia now the biggest cause of death in the UK, my family’s story is hardly unique; sadly, we are one of thousands struggling to make sense of the incomprehensible. Alzheimer's is a grim story of decline, relentlessly stripping a human being of everything that makes up who they are.

Medical literature blandly speaks of changes in the brain caused by the build-up of beta-amyloid and tau proteins, which give little hint of the wanton destruction of memory, thought and language that ensues.

Far more than being forgetful, a healthy human brain is reduced into a shrunken facsimile of its former self, locking the sufferer out of reality and into a hinterland of fear and confusion. As the brain erodes, the sufferer loses recognition of surroundings, triggering distress, anger and violent outbursts. They might start to wander, as if looking for something or someone, and will increasingly confuse children and grandchildren for siblings or even parents.

Slowly the sufferer will retreat deeper into his or her own history. Meaning that if the day comes that my father does not know who I am, it will be because he has regressed to an era before I existed.

There are drugs to help slow the progression of certain symptoms, but to date there is no cure. Alzheimer’s remains a death sentence, played out one terrible degree at a time.

What makes this even harder is that I live thousands of miles away. As my father faces this in the UK, I am in the UAE, my home for the past 16 or so years.

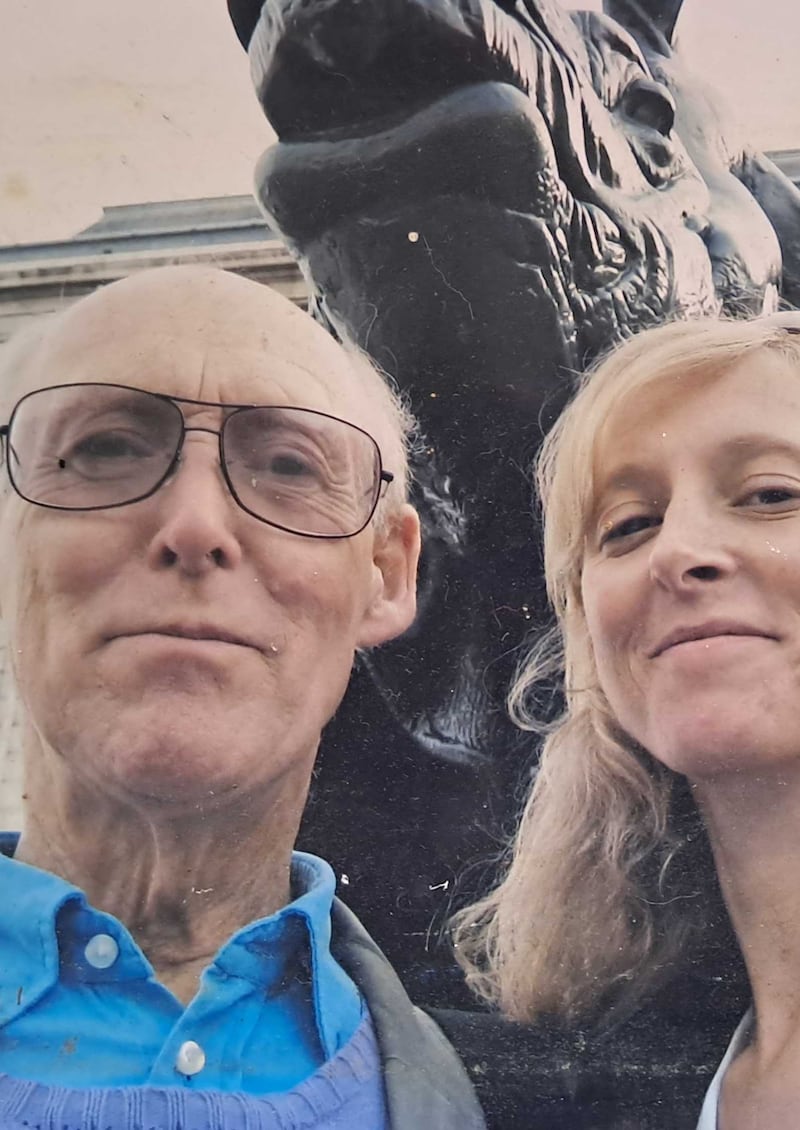

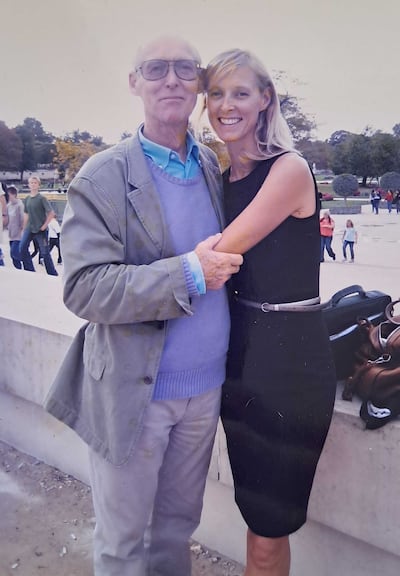

Like many with elderly parents, I have been acutely aware of my father's advancing age for some time, cherishing each moment I get to spend with him. He is without question my favourite person on the planet and losing him will be extremely hard.

Losing him to Alzheimer’s, though, seems cruel beyond belief. Having already watched one parent die in increments – an alcoholic who was floored by cancer – the thought of having to go through it again is, perhaps selfishly, depressing. When my mother died (of starvation owing to the tumour in her throat), I requested my father immediately attain immortality, as I wasn't sure if I could handle the experience again.

“I will see what I can do,” was his reply. We were both only half-joking.

My father may be pushing 90 – a good innings in any era – but he loves living and squeezes joy from every moment, from striking up conversations with total strangers to crafting a home with his bare hands. Now, his hands may be ruined by age and his gait as wobbly as a toddler's, but the happiness remains. He still sees beauty wherever he goes.

Like many expats, I grapple with the guilt of being so far away, despite my father having always encouraged my brother and me to explore the world. I like to think he has always been proud that his children, and now the next generation of grandsons, live in far-flung lands. Since his diagnosis, however, it is starting to feel like we've abandoned him.

With three visits so far this year, I am watching the disease sink its claws into him. He can no longer remember how to use a phone, and has begun compulsively stashing things behind the sofa, “to foil burglars”. On my last trip home, he was panicked and activating new bank cards – the latest in a long line of replacements – and fixating on an irrelevant piece of paper.

As is so often the case in such a situation, his wife – my stepmother – has become my father's carer, and I am at a loss about how to support her. How do I help as she watches her husband crumble to ash in front of her eyes? From the distance of the Middle East, my soothing words feel like empty platitudes.

In her late 70s herself, she needs practical help to deal with my father's daily crises, from him squirrelling away crucial correspondence to falling over. How do I help pick him up off the floor when I am more than 5,500 kilometres away?

All my adult life I have bounced around the globe, marvelling at its diminutive size and the wonder of airline travel. Now, I am acutely aware about how big the planet actually is, and how slowly even the fastest aeroplane travels.

Years ago, while my mother lay dying in hospital, I begged my father to hurry from his then-home in France. You need to get here now, I pleaded, willing him to arrive before she died. “I can’t,” he quietly explained. He was right. Even being in the next town is too far away when a life is slipping away.

Living in the Middle East – which has long delighted me as being “only” six hours away – I might as well be on the moon for the time it will take me to reach home in an emergency. With no travel method yet invented that can transport us between countries in the blink of an eye when really, truly needed, I am trying to make my peace with the reality that my father's death or, worse, his progressive slide into dementia, will most likely happen while I am not there.

Like others before me, I am weighing up the choice of packing up a life, career and home to move back to witness a protracted death that could take years; or staying put, and learning to live with the guilt. It feels like an impossible choice, like my hope my wonderful father dies before he is ravaged by this appalling disease. It sounds terrible, but it comes from a place of love. I do not want him to suffer, fearful and lost, but instead to go out the way he has lived life – skipping to his own artful beat and doggedly on his own terms.

By choosing to remain in another country, on a different continent, the chance of me being there when my father dies is vanishingly small, I know. And this troubles me, as I believe that standing witness to someone's final moments is both a great privilege and an act of love.

I was with my mother when she passed and I have chosen to regard it as her final gift, showing me that whatever the manner of dying, the moment of death can be quiet and peaceful. I now wish a gentle death for my father, as befitting his tender soul.