A nuclear fusion start-up says it has hit temperatures of 37 million° Celsius at a “fraction of the complexity and cost” of its rivals.

Scientists at Zap Energy say they have “joined the rarefied ranks” to make a plasma that replicates the core of the Sun.

The extreme heat is needed to make parts of atoms fuse together – unleashing massive amounts of carbon-free energy, as the Sun does.

Funded by oil and gas giant Chevron and the Bill Gates-founded Breakthrough Energy, scientists at US company Zap are among many trying to make this work on Earth.

What they have not yet done is produced more energy than it costs to achieve the massive temperatures, a key milestone known as “energy gain”.

The first energy gain was reported by US scientists in 2022, raising hopes for fusion's potential as a near-limitless power source that could help tackle climate change.

Zap's chief scientist Uri Shumlak said the company's tests “paint a good overall picture of a fusion plasma with room to scale towards energy gain”.

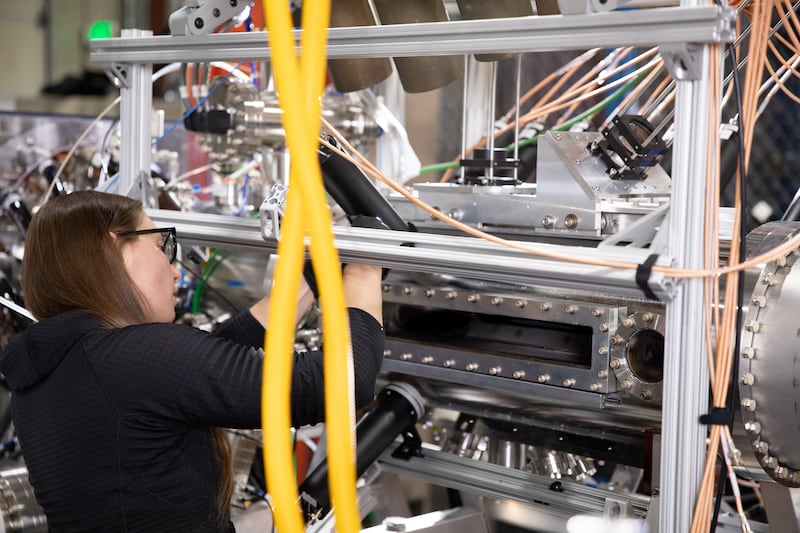

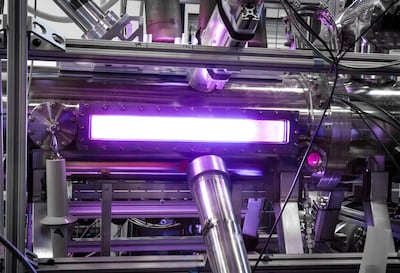

The Zap device is based on a concept called a “Z pinch”, in which the intensely hot plasma is confined in a small space, only few metres wide and high.

Leading fusion research uses a much larger machine called a tokamak to trap the plasma in a magnetic cage.

In this “hot soup” of particles, parts of hydrogen atoms – readily available from water – would collide and produce millions of times more energy than burning oil or coal.

Compared to existing nuclear power plants, fusion wouldn't generate long-term radioactive waste requiring storage for thousands of years.

The Z pinch has previously stymied scientists because the plasma would quickly cool down as though there were ice cubes in the soup.

However, Zap Energy says it has mastered this problem with an experiment that lasted “long enough to produce very high temperatures” of between 11 million Celsius and 37 million Celsius.

The temperature at the Sun's core is about 15 million Celsius.

Ben Levitt, the company's head of research and development, said it had hit a “sweet spot where the temperature, density and lifetime of the Z pinch align”.

“These are meticulous, unequivocal measurements, yet made on a device of incredibly modest scale by traditional fusion standards,” he said.

“We’ve still got a lot of work ahead of us, but our performance to date has advanced to a point that we can now stand shoulder to shoulder with some of the world’s pre-eminent fusion devices, but with great efficiency, and at a fraction of the complexity and cost.”

Plans are afoot in the UK to get a prototype fusion plant up and running by 2040.

This means it is doubtful whether any fusion breakthrough would come in time to achieve the world's net zero goals by 2050.

However, proponents of fusion say it could be a long-term energy source beyond that date.

“It would be counter-intuitive if not outright silly to say we’ve reached the deadline in 2050 so now we don’t need it any more,” International Atomic Energy Agency Chief Rafael Grossi said last year.