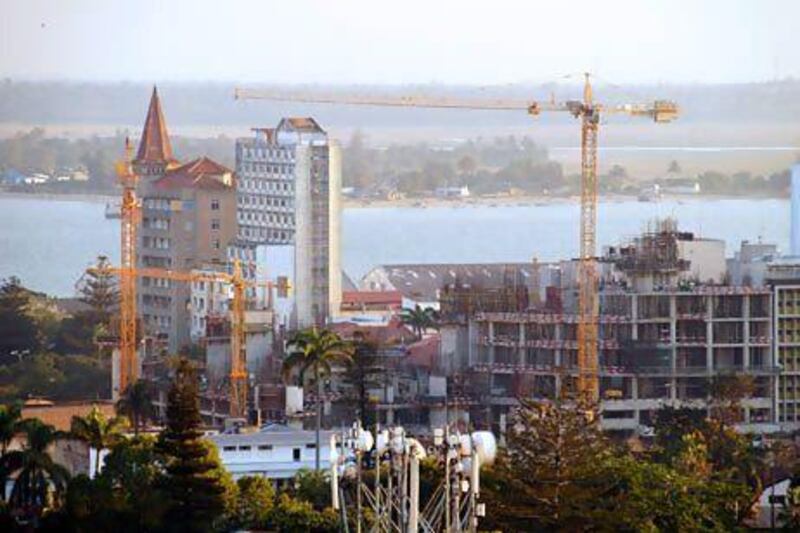

A quick glance along Maputo's skyline is enough to tell you big changes are underway in Mozambique's capital city.

Large new commercial and residential buildings are rising up along the coastline. The number of cranes that punctuate the city's skyline has increased significantly over the past year.

Mozambique's northern province, Cabo Delgado, has experienced its own construction boom in response to significant natural gas finds in the Rovuma Basin. International companies are building their presence in the country and vying for participation in the development of Mozambique's recently discovered resources.

Tete province, where there are large coal deposits, is continuing to develop as mining majors Rio Tinto and Vale work on infrastructure to export large volumes of coal to international markets.

It comes as no surprise, therefore, that Arabian Gulf investors have turned their attention to the southern African country. While growth has stagnated in the West due to the global economic slowdown and euro-zone crisis, Mozambique's economy has grown significantly over the past decade. Last year, Mozambique's real GDP stood at 7.4 per cent. The African Development Bank expects growth to rise to 8.5 per cent this year and 8 per cent next.

As an investment prospect, Mozambique is attractive for its stable government, young workforce and growing demand for consumer goods and services. These features have caught the attention of the Gulf and the UAE in particular, which has increased its equity participation in Mozambican projects significantly.

Last year, the UAE was Mozambique's largest investor, according to the Mozambican Centre for Investment Promotion (CPI).

"Traditionally, it was countries like Portugal, Germany and Switzerland that invested in Mozambique, says the CPI project manager Emilio Ussene.

"Now it is China, the UAE, Mauritius and Brazil."

Investments from the UAE totalled $309.14 million last year for transport, communication, tourism, agriculture, industry and services projects. CPI estimates about 274 new jobs for Mozambicans will be created from these investments this year. The largest investment, was provided to fund consultancy services from the US's Halliburton to further explore Mozambique's oil and gas potential.

The figures may exaggerate the UAE's participation as they include all investments that arrive through the UAE, irrespective of origin. By routing investments through the UAE, investors can take advantage of the double taxation agreement.

Nevertheless, the UAE has an established presence in Mozambique, which it is set to build upon.

Dubai's DP World is a partner in the Maputo Port Development Company, alongside the Mozambican railway company and South Africa's Grindrod. DP World was granted a 15-year concession to operate the port in 2003, which was later extended for another 15 years with an option for a further 10 years. The country's location for shipping is one of Mozambique's most important assets.

Traditionally, Mozambique's finances have been dominated by aid. In the aftermath of the civil war, which ended in 1992, financial assistance from around the world has flowed into Mozambique, with Gulf countries often taking the lead.

Kingdom Holding, which is run by Saudi Arabia's Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal, established Letshego Financial Services in 2011 to invest in African countries, including Mozambique.

The Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development has a long-standing relationship with Mozambique and has provided US$84 million in loans for infrastructure and agriculture.

The Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa has provided funding for education and power projects.

A lot of Mozambique's funding continues to take the form of aid but the focus is shifting towards long-term investment for profit.

Only a few years ago, 60 per cent of spending was aid-based. Now it is about 40 per cent. Invest AD and Morocco's Attijariwafa Bank announced plans to launch an Africa fund in November last year. International banks are also keen to take advantage of the high demand for retail banking. Barclays, Standard Bank and First National Bank have all increased their presence in Maputo.

However, it is the country's natural resources that are attracting the most interest from international companies.

Gas reserve estimates vary but the National Enterprise of Hydrocarbons has placed it at about 250 trillion cubic feet. Other estimates are more conservative. The government plans to raise $6 billion to $8bn a year in gas exports, which would treble the country's overall exports. The National Petroleum Institute has said tenders for several new blocks will be launched later this year.

In a visit to Dubai in March, the president Armando Emilio Guebuza encouraged the Dubai Chamber to invest in Mozambique's gas sector as well as its mining, banking and tourism projects.

Many international energy companies are moving staff to Mozambique, prompting a rise in demand for commercial and residential properties.

"Until four or five years ago, the market was very small. We made a turnover of €10-15 million," says Rui Carrito, the chief executive of the Portuguese construction company Soares da Costa.

"In recent years, we have seen the market grow. In 2013, we hope to have a turnover of €90 million."

While Portuguese companies traditionally dominated the Mozambican construction sector, there have been several new entrants to the market.

"In the last two to three years, we have Chinese, Brazilian, Indian and Spanish companies [enter the market],"says Mr Carrito. House prices have increased dramatically.

"Prices have been increasing due to big demand and little supply," says the Maputo-based real estate agent Gonçalo Marques.

"The biggest increases can be seen in the centre of town where prices have more than doubled over the past four to five years."

But for all of the potential, doing business in Mozambique can also be difficult.

Parliamentary and presidential elections are due to take place next year and campaigning has taken its toll on some projects. The government recently introduced employment ratios that oblige companies to employ 10 Mozambicans for each expatriate.

"No company is going to bring an expat [unnecessarily] because even if you pay the same wage, you'll still pay twice as much on the expat than to hire a Mozambican," says the USaid representative, Antonio Franco. The federal agency is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid.

"If they hire an expat it is because they can't find the skills [locally]," says Mr Franco.

A lack of property rights can also deter foreign investors. Under Mozambican law, property cannot be transferred to the private sector. Companies can apply for concessions to build on the land, which they control for a given period before handing it back to the state. The concession is only valid for a specific purpose and if the holder of the concession wants to sell it, the company must first prove that the buyer is just as able to carry out the development.

This is particularly problematic for gas companies as they often want to sell off portions in their concessions. In March, CNPC, China's largest oil producer, agreed to buy a 20 per cent stake in a gas concession for $4.2bn from Italy's ENI SpA. Two of the operators of an offshore field in the Rovuma Basin plan to sell a stake worth between $5bn and $6bn in the project. Mozambique imposes a capital gains tax of 32 per cent but this is always up for negotiation with the government and can be as little as 12 per cent.

Taking over an onshore concession means negotiating with the current users of the land.

"Once you get a licence to develop the land, you have to negotiate with the people living on the land," says Titos Munhequete, a geotechnical engineer at Golder Associates in Maputo.

"You have to pay the people for what they have built on the land."

Setting up a new company can also be difficult in Mozambique. "For big business, you have to go through a long and painful process," says KPMG's Maputo-based senior partner Filipe Mandlate. "It can take between one and two months."

Mozambique does not allow for "shelf companies", which can be created and left dormant with the intention of selling to companies that want to establish their presence in the country quickly.

Finally, Mozambique runs the risk of harming its traditional exports once it begins to export large volumes of gas in a relationship known as "Dutch disease".

Mozambique's specialist exports, such as shrimp, are less likely to be affected but cash crops will be hit as the value of Mozambique's currency rises.

Already, Mozambique's corn producers have been affected. Much of the corn consumed in the capital is imported from abroad as it is cheaper. This problem is affecting the 80 per cent of Mozambique's population that works in agriculture as well as the investors that have invested in food production for export.

Mozambique is evolving rapidly. For some investors, the evolution will be lucrative while other investors will struggle with logistics, changes in the economy and navigating local rules.

Much uncertainty surrounds Mozambique's potential. But the savvy investor who is able to take a long-term approach, the potential is high.