The death of Arab secularism is the story of a country that no longer exists and a world almost impossible to imagine.

That world can be glimpsed in old newsreels from the Arab cities of the 1950s and 1960s. The cities of the post-war period - Cairo, Beirut and Damascus, Baghdad and Aden - look much the same as many developing countries of the time: American-built cars, European-style suits, a certain easy mingling of men and women.

Unseen is something difficult to describe, but immediately apparent to anyone familiar with the Egypt or Yemen of today: the thick beards of men and the tightly wrapped headscarves of women - symbols of religious devotion, but also symbols of a public expression of Islam - were almost entirely absent from the new urban world then being created.

The vision of the future the men and women in those over-saturated newsreels had, how they saw their modern world unfolding, cannot easily be understood.

But it can perhaps be surmised from a joke, told by Egypt's leader Gamal Abdel Nasser to an audience in the years after the Muslim Brotherhood was accused of attempting to assassinate him. Nasser described meeting with the Brotherhood's leader in 1953 in an attempt to reconcile the group with his leadership. (Nasser doesn't mention whom he met, but it was most likely Hassan Al Hudaybi, a judge who led the group for 20 years from 1951.)

"The first thing he asked me was to make the wearing of hijab mandatory in Egypt," says Nasser, "and to force every woman walking on the street to wear a hijab." The crowd laughs and Nasser hams it up for them, looking perplexed at such an outlandish request. "Let him wear it!" shouts an audience member, and the crowd erupts in laughter and applause.

But that's not the punchline. Nasser tells Al Hudaybi he knows the Brotherhood's leader has a daughter studying medicine, and his daughter doesn't wear the hijab. "Why haven't you made her wear the hijab?" he asks, before delivering a knockout blow: "If you cannot make one girl - who is your own daughter - wear the hijab," he says, "how do you expect me to make 10 million women wear the hijab, all by myself?" The crowd roars its approval.

Nasser's joke is instructive for the world view it implies. The middle and upper classes of 1950s Egypt considered it ridiculous that the wearing of the hijab could be enshrined in law. Most did not wear it; they considered the proper role of religion to be private, outside the realm of government and politics. Nasser himself explicitly declared the same thing.

Contrast that with today's Egypt, and indeed the wider Arab world, and it is clear how much has changed in just half a century.

Nasser was speaking to a particular class of Egyptians, an educated elite that saw secularism and the separation of religion from political life as inevitable hallmarks of a new Arab modernity. That elite still exists, both in Egypt and abroad, still hoping for a return to a now-vanished world. But the world view has gone. The days when the very notion of large numbers of women wearing the headscarf was unthinkable have passed into history. Nasser's punchline is now Egypt's reality.

Why did the Arab world change so rapidly? How did the very idea of religion as existing outside of the public sphere vanish so completely? Secularism, a particular notion of secularism that existed in the Arab world, has all but vanished as a political force. There is no major political party in the Arab world that would today be understood as secular.

To understand how that happened requires entering a country that no longer exists. The United Arab Republic (UAR), a nation formed in 1958 by the merger of the Egypt of Gamal Abdel Nasser and a Syria dominated by the Baath Party. It disintegrated in 1961. What happened in those three years so devastated the politics of secularism that the movement has yet to recover in the Arab world.

>>>

The ideas that animated the founding of the United Arab Republic and the politics of the postwar era emerged much earlier, at the very start of the 20th century.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire also brought with it the demise of the institution of the Islamic caliphate, and with that the end of religious authority as the political basis of government in the Arab world, and raised questions that the United Arab Republic later sought to answer.

Questions about the proper role of religion in a state had existed for centuries, all the way back to the early days of the caliphate. But the task of creating a new basis for political authority took on a renewed urgency during the colonial period, starting from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1799 and the subsequent destruction of the Ottoman Empire.

Though 600 years old by the start of the 20th century, the empire was itself merely the latest incarnation of the caliphate, the political framework within which most of the Arab world had operated since the coming of Islam.

The Ottomans derived their political legitimacy from religious authority. It was because they claimed to uphold the principles of Islamic law that they gained the political legitimacy that allowed them to rule an empire that stretched across three continents.

As the colonial period began to chip away at the territories of the Empire, the growing discontent within the Arab and Islamic worlds expressed itself in finding new ways of conducting politics; primarily to meet the threat of the West, but also as a way of emulating the West, with its clear military superiority. A new politics became an urgent project, and Arab thinkers looked to three familiar bases for political authority: a return to religion, the authority of individual nation states, and secular ideals.

These same ideas, articulated and debated in different ways throughout the 19th century as Europe for the first time really encroached on the authority of the caliphate, received a new impetus after the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, and with it the caliphate, in 1924.

The arguments about secularism in this period - post-caliphate - were about the proper basis for the unity of a state. The caliphate had taken with it the political structure that had provided an identity, a unity, an expression of faith and a vehicle for societal progress for the Arabs and other ethnic groups for a millennium and a half. This was an enormous political shock, and its impact should not be underestimated.

What could replace it? The forging of the identities of successor states took place against a background of occupation and colonialism by foreign powers. While the Turkish lands were going through the same process, they already had the institutions and people of government in place.

The Arab lands, at the time, were not countries - they were regions whose borders were forcibly drawn by colonial powers. These new nation states now had to reinterpret the basis of their states and secure new national governments, all with foreign involvement and the attendant domestic jockeying for political power. The whole region was in flux. The arguments expressed were less about the type of society that the new states would have and more about their political structure. Arab secularism in this period was less about removing the influence of religion in daily life, and more about securing a political basis for a state. Religion was an important part of daily life in the Arab world and every Arab country had within it Muslims, Christians and Jews, as well as a plethora of other faiths. Religion was not going anywhere. Ideas of secularism were ideas about the basis of the state, not the composition of the society.

The caliphate was gone, and with it the familiar political structure. A new one was required. If not on religion, then on what basis, the Arabs wondered, could they build a modern state?

>>>

The answer came in language and in land. For some, the narrow nationalism of one country was the best way to unify the peoples of the new states: all those who shared the common borders of a country would choose to live together in political community.

But others looked to a broader bond. Arabic, the common language of the Arab world, and the culture that surrounded it, would become the basis of this unity. Instead of a state held together by religion, this would be a state held together by a common language. The language was the basis of the emerging conceptions of pan-Arabism, the idea that all the Arab peoples from the Atlantic to the Gulf, were one people and ought to live in one nation.

Not all who identified with this trend believed in a pan-Arab state. For Taha Husayn, one of the preeminent Egyptian writers of the 20th century - and one who, in the interwar years, did much to glorify Arabic as the common language - readily accepting both those premises led to Egyptian nationalism, rather than pan-Arabism.

Pan-Arab ideas found their clearest expression in the writings of Sati Al Husri, a Yemen-born Syrian who worked for the Ottoman Empire in its declining years. All those who spoke Arabic were Arabs, declared Al Husri, and as such they ought to live as part of the same political community. The controversial part of Al Husri's views was that he believed Arabic speakers were Arabs independent of whether they wished to be or not: the Arab world was not a nation formed by choice or by common consent, but mandated by a common language and culture.

It is unsurprising that the main rival to Al Husri's pan-Arabism was a pan-Islamic state. In the years after the end of the caliphate, most Arabs still saw themselves living as part of the Muslim global community. Al Husri had to tread carefully to delineate the differences in approach.

In his seminal essay on the decline of secularism in the Arab world, the author and analyst Paul Salem outlines his accommodation: "Although Husri's outlook was decidedly secular, he avoided a too-specific designation of the role of religion in Arab society for fear of alienating a still largely religious audience and often emphasised the central role of the Arabs in Islam in order to downplay the conflict between the Islamist and Arab nationalist points of view."

Again and again, these two trends clashed and reformed, as the tumultuous events of the mid-20th century played out across the Middle East. In the post-war era, the pan-Arabist trend manifested itself in the forms of a person and a party.

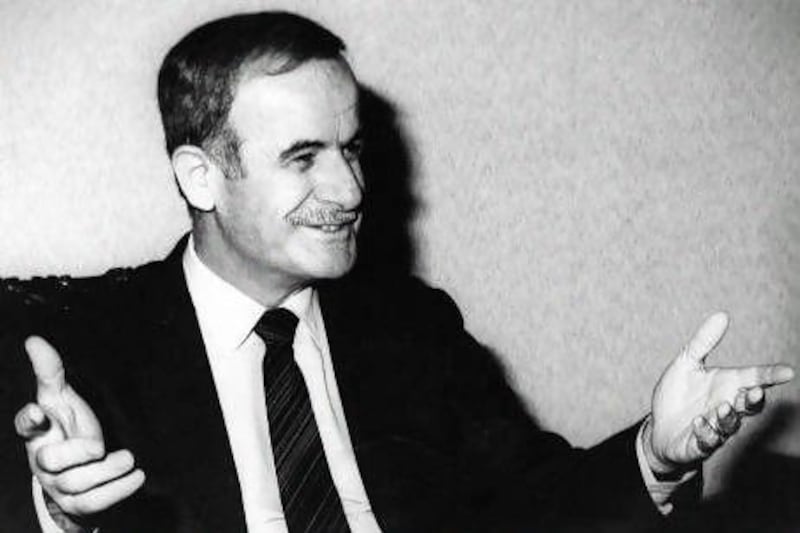

The person was Gamal Abdel Nasser, who took power in Egypt in 1954.

His popularity soared after the Suez crisis of 1956 and the widespread impression that Nasser had taken on the former colonial powers of Britain and France and won. Nasser began to export his brand of politics. Having started as an Egyptian nationalist, he rapidly came to believe that the nationalist revolution ought to be exported to other Arab countries, and then to believe in pan-Arabism.

The party was the Baath Party, a movement which, starting in the late 1940s, rapidly gained wide popularity in the Levant. The Baath believed in a secular basis for the state, which would reduce religion, particularly Islam, to a private role. Later, the Baath adopted socialism and a Marxist conception of permanent revolution, but its animating ideas of political community remained those of a secular state.

Wrapped up in both ideas, of Nasserism and Baathism, were the notions of freedom from foreign interference and the unity of the Arabic-speaking peoples that had animated movements for decades. With the rise of the Soviet Union, another element was added, that of socialism.

But the secular conception of the state that animated both nationalist and pan-Arabist politics was widespread in political life. It is difficult to overstate the degree of popular attachment to a secular state among the political class. With the exception of Saudi Arabia, no country of the Arab world, from Sudan and Yemen, to Iraq, to Algeria in the Maghreb, was without its secular, nationalist parties.

It is possible to say that, from the 1950s to perhaps even the 1980s, the strongest political trends in the Arab world were secular.

These two movements came together in the United Arab Republic. Much history lay behind the decision to merge Egypt and Syria, a familiar combination of high ideals and low politics. But there was also a historical momentum, unleashed by Nasser's political victory of 1956 at Suez: within two years, Egypt and Syria had become one country, Jordan and Iraq attempted political union, and a revolution had toppled Iraq's monarchy.

It was the Baath Party of Syria that proposed and pushed through the union, but the UAR had wide support - it was ratified by referendums in both countries - and was about much more than merely uniting.

In essence, the UAR was an attempt to find a political vehicle that could sustain Nasserism.

The ideas of Nasserism were intimately bound up with the person of Gamal Abdel Nasser. But while his personal charisma could sustain the initial movement, it needed an organising political structure to allow it to rule two such widely disparate nations as Egypt and Syria.

Nasser's party, the Arab Socialist Union, was essentially a vehicle for Nasser and based on the particular political circumstances of Egypt. The Baath Party had a more coherent, more widely applicable ideology, with branches already existing in Libya, Sudan and Jordan.

Yet the project of the UAR collapsed because it could not find an answer the same questions that were raised after the end of the caliphate: what was the proper basis on which to build a state? How could such a vast region as the Arab world live in political unity? What could hold together a state of that size?

Nasser felt the force of his personality could be that glue. But while his charisma could perhaps provide the animating impetus, a stronger structure was required to rule.

In the case of post-Ottoman Turkey, the answer was a more straightforward interpretation of language and land. The concept of a Turkish people living in a relatively defined geographical location and speaking a broadly common language allowed for a state within the bounds of the already existing Ottoman institutions of state.

But for the Arabs, the question was harder. If the Arabs were one people from the Atlantic to the Arabian Gulf, how could they live together in a political community?

It was for that reason that the United Arab Republic experiment mattered. The UAR was the first time such a union had been attempted seriously, the most important attempt for more than one Arab country to live in political union. That the UAR failed suggested there was no way for the Arabs to create a unifying state that relied on secular ideas.

That left two options, two ways of being one nation: either a vast nation held together by a bureaucracy, or a nation unified by faith.

That the Arab world could not perhaps be united under one government was not yet widely accepted.

>>>

The United Arab Republic represented the high-water mark of Arab nationalism. Never again would two large Arab countries unite in that way. Nasser tried again for a union of Arab countries, entering into discussions with Iraq and Yemen. Iraq discussed political union with Syria; Syria proposed union with Egypt and Libya. But nothing on the scale of the UAR ever materialised.

There were other setbacks in the years after 1961. The split of the Baath Party into a Syrian and an Iraqi faction in 1966, and the war of 1967. But with the death of Nasser in 1970, the region lost the only leader capable of projecting his political personality across the Arab world. The force of Nasserism was always the force of Nasser: he left behind no political party able to institutionalise his ideas.

Neither Nasserism nor Baathism had a monopoly on secular ideas of political community. But the failure to forge a synthesis between the two most powerful secularising movements of the modern Arab world raised questions about whether a community as large and diverse as the Arab world could be held together by the unity of language and land.

Political ideas need political vehicles to sustain and renew them. But Nasser left no political institution capable of doing so for the Arab region. The sole popular political vehicle left for the ideas of pan-Arabism and secularism was the Baath Party.

But the Baath, having completely taken power in both Syria and Iraq by 1963, discarded their ideas and did something very dangerous, something that was inherent in their constitutions: the Baath sought to lead society alone.

That meant that other political trends, on the left with communism, on the right with Islamism, were forcibly driven underground and persecuted. That left only Baathism - a Baathism that increasingly became devoid of ideas, because once in power there was no more need for them as animating ideals for the polity.

With access to the levers of power, the Baath Party had no need for genuine mass political movements that could mobilise a political base and - crucially - renew the leadership with new ideas and new people.

The Baath Party in Iraq and Syria focused their energies on ruling their respective, but markedly different, countries: persecuting the intellectuals, who were mainly secular nationalists, as threats to the regime; persecuting political religious movements while appropriating some appearance of religion; creating, in Syria under Hafez Al Assad, the illusion of participatory democracy, and, in Iraq under Saddam Hussein, an overwhelming cult of personality that stifled real political discussion. The Baath so emptied politics of ideas that there was nothing left.

The fact that those who held the reins of Arab governments in this period were secular - and backed by business and military elites who were also secular - in fact proved to be their undoing. The great intellectual rival of Arab secularism, Islamism, had precisely the opposite circumstances. Finding themselves hunted everywhere, those movements that wished to put religion at the heart of their politics had to create a mass movement with strong support and seamless organisation.

The era of the Baath is now ending. When Saddam Hussein was deposed in 2003, the Iraqi Baath Party went with him. Whatever happens in Syria, the reaction of Assad's son to the uprising has destroyed the always fragile notion of a party for all Syrians that the Baath propagandised. While the Baath will remain a trend, like communism and Marxism exist in the Arab world today, there is unlikely to be any revival.

In the same way, secularism as an idea hasn't died. One can see it animating the politics of young people in Tahrir Square, politicians in Tunisia, liberals in Lebanon, and in what the Syrians and Yemenis and Libyans are calling for in practice. Nor has the idea of a separation of politics and religion faded from the business and military elites of most of the republics.

But secularism as politics does not exist in any organised, large-scale political form. Secularism, like any political idea, requires a political vehicle through which to express itself. And those political vehicles have yet to revive with any large degree of political support.

The men who crowded into that grand hall in Cairo to hear the doyen of Arab political life make jokes about Islamists could little have imagined the world their children would be bequeathed. The secular states they imagined would spring up across the region seemed inevitable to them, the next necessary step in the political evolution of a vast region.

Yet small events can sometimes shake even large movements. The clash of politics, policies and personalities in two cities of the Arab world within three short years finally sounded the death knell for the unifying viability of secularism, and a political force that had animated the fighting of wars and the forming of nations passed into history.

Faisal Al Yafai is a columnist for the National.