To the east of Casablanca, in the working class neighbourhood of Hay Mohammadi, lies an enormous, dilapidated set of buildings. The yellow paint is peeling off their monumental facades, decorated with green ceramic tiles and patterned windows. Casablanca's abandoned 20th- century slaughterhouse is an immense and surprisingly attractive architectural complex. Built in 1922 by Georges-Ernest Desmarest, a Parisian architect, in the so-called Neo-Mauresque style, which combines clean Art Deco lines with traditional North African motifs, it was one of the great public works of the French protectorate in Morocco.

Today, a collective of Moroccan artists, architects and activists are trying to fashion a new future for the space, one in which it would be the site of an entirely different sort of production. "We call it a culture factory," says Abderrahim Kassou, an architect who is leading the effort, "because we're in a city with a great industrial tradition, in a neighbourhood with some of the biggest workers' housing projects. And because we want to get out of this mentality of just consuming culture made elsewhere and into one of producing our own culture."

Yet the transition hasn't been easy. Despite organising nearly 50 cultural events in the space in the last year and half, the art collective has yet to consolidate either official status or institutional funding. "We've bitten off a lot," admits Kassou, a tall, imposing man with a wry sense of humour. Kassou and Aadel Essaadaani, his friend and collaborator, who is an expert in art and event management, took me on a tour of the site recently. The slaughterhouse's past function and its current vocation overlap in startling ways. The ceilings of the rooms are crisscrossed with the rails and pulleys that used to transport livestock, but the large airy spaces are perfect for performances. One of the huge stables is still home to a few sheep and donkeys; the other, across the way, is dedicated to visual art exhibitions. A courtyard has been turned into a skate park. Everywhere, the crumbling walls are decorated with graffiti, wall paintings, torn posters, the remains of film shoots and art installations.

Many still "don't understand the dimensions of the project," says Kassou; "they think it's just some kids having fun." On the contrary, Kassou and his collaborators hope to fill an institutional void by offering young artists and would-be culture professionals the chance to meet, get training, rehearse, create and exhibit; and to make art accessible in a neighbourhood not usually targeted by cultural initiatives, by offering free, open-to-all activities and shows.

The kind of space envisaged in the old slaughterhouse is the natural result of the cultural effervescence of the last decade in Casablanca, during which a new generation of artists, filmmakers and above all musicians has animated the city. The phenomenon has even earned its own name, "nayda," a word derived from the Arab verb "to rise" and lifted from Casablanca youth slang. When I visit again a few weeks later, one of the slaughterhouse's cavernous halls is filled with the sound of voices, laughter and power drills. About 20 people are at the venue, attending a workshop run by the artist and designer Khadija Kabbaj. "We realised there isn't really anywhere to sit down," says Kabbaj.

Today, participants are building chairs and whimsically decorating them to reference their surroundings. One is covered in flakes of paint gathered from the slaughterhouse walls; another is painted to look like cow hide and has weeds sprouting from its armrest. One chair is even set aflame — a nod to the fire that demolished part of the slaughterhouse in 2004. The group includes art students, middle-aged women, and the young Mohammad Safsaf, who volunteers at a neighbourhood association for children. Before the slaughterhouse was opened to the public, says Safsaf, "we never imagined it was like this. Now we can see it. It's a beautiful place." Safsaf and his friend Rachid have decorated their chair in the in the colours of the neighbourhood's beloved football team Raja.

Meanwhile, the sound of an electric keyboard wafts through the immense building, accompanied by guitar chords and an ethereal female voice. A trio are rehearsing in a nearby building, in a dark room plastered with music posters and graffiti. Above their heads, someone has written on the wall in Arabic: "Together in defence of freedom and dignity and the right to create." Beyond lies a large esplanade in which Casablanca's popular hip-hop, rap, reggae and heavy-metal groups have played open-air concerts to packed crowds.

The decision to close the slaughterhouse - and replace it with modern municipal facilities elsewhere - came in 2000. Local artists immediately suggested turning the space into a cultural site, but their negotiations with the city led nowhere. It was only in 2009 that a dozen Moroccan civil society groups managed to sign an agreement with the city to use the space for a year. The CasaMemoire group - an association dedicated to educating about and preserving the city's 20th-century architecture, which Kassou heads - took the lead.

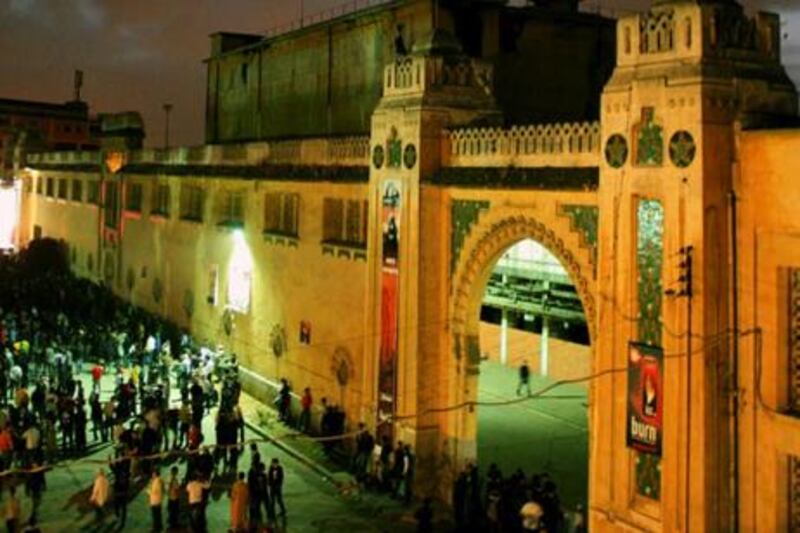

In the spring last year, 250 artists and 30,000 curious visitors converged on the space for its inaugural weekend, which featured continuous screenings, concerts, installations, dance recitals and more. It was by all accounts a riotous success. "We had no idea how it would go," says Kassou. "We let everyone in for free. There was a really mixed audience: families from the neighbourhood, kids with long hair and piercings, ministers, my mom."

Since then, the old slaughterhouse has hosted nearly 50 cultural events. The space is dedicated to contemporary and urban art, meaning anything from conceptual art to graffiti, from dance to hip-hop, from fashion to film. Many emerging and well-established artists have exhibited, partly because, says Kassou, they have "a freedom here that they don't have in a conventional gallery." Kassou and his colleagues have kept the events coming at a sustained pace largely because, he says, they want to make the slaughterhouse's transformation into a cultural landmark "irreversible."

Their urgency is understandable, given that the agreement with the municipal authorities expired last January. Kassou and his colleagues have asked for, but not yet signed, a new, long-term agreement. In the meantime, everyone at the old slaughterhouse is, technically speaking, squatting. The space is running on "a lot of energy and no money" says Kassou. A committee of volunteers from the groups involved handles everything. Kassou's association, CasaMemoire, is running a 300,000 Moroccan dirhams (Dh133,000) deficit just to keep things going.

Eventually, Kassou figures it will cost 10 million dirhams (Dh4,400,000) a year to put in place a permanent administration and, above all, launch the kind of ongoing exchanges, artists' residences, workshops, neighbourhood outreach and training programmes envisaged. But it's impossible to raise funds until the space's cultural vocation is made official. Meanwhile, the Casablanca city council continues to drag its feet - the Minister of Culture has never visited.

In Morocco, as in many other Arab countries, the state's cultural policy is largely limited to supporting official institutions, prizes and festivals, high-profile events meant to present the country in a good light, and to attract tourists and positive press. A cultural centre in a low-income neighbourhood, run by a loose coalition of independent groups that targets local audiences and groups and features avant-garde and street art doesn't quite fit with the vision of "culture" most government agencies and municipalities are eager to promote.

The project also faces the general lack of interest in preserving 20th century buildings (which are not yet seen, in most of the Arab world, as having any architectural value) and the unease of public officials with any truly grass-root initiative. In theory, Moroccan law allows associations to take over unused public space for cultural purposes, but in practice, this would be a first. And that not just here, but across the Arab world, where the idea of repurposing large abandoned industrial spaces into art venues - something that's become quite common in Western cities - is still unheard of.

Kassou and his colleagues are well aware of the ground-breaking nature of what they have already achieved. The takeover and subsequent makeover of the city's old slaughterhouse is, as far as they are concerned, a fait accompli. "We'd like a much more solid support from the city," says Kassou. But "we're not waiting for them to organise things." And they're not going anywhere. Sooner or later, they are sure, the new agreement will be signed. Because "there's no possibility," says Kassou, matter-of-factly, "of stepping back."

Ursula Lindsey, a regular contributor to The Review, lives in Cairo.