The premise of the South African writer Ivan Vladislavic's genre-blending collection The Loss Library sounds fairly simple at first - to write a personal book about the stories he could not write, with thoughts on what prevented him.

In theory, this book would be perhaps 50 per cent creative non-fiction, an autobiographical look back through old notebooks that form, among other things, a chronicle of the writer's past ambitions. Fiction could be included by giving readers snippets of the unfinished stories, which Vladislavic does, and if the book sheds new light on the modern writer's craft and avoids looking like a bunch of old fragments published for fun or profit, it might yield good results.

It's a task only a seasoned writer could manage without boring readers, and Vladislavic's success with it makes this short book rather remarkable. His work to date includes novels, The Restless Supermarket (2001), The Exploded View (2004), and The Folly (1993), several short story collections, including Missing Persons (1989), and a celebrated work of nonfiction, Portrait With Keys (2006).

His reputation has been growing steadily and The Loss Library, filled with choice aphorisms about the writing life, is more than a charming account of artistic failure. It's worldly, erudite and funny as it liberally gathers in tropes from the magazine essay, the writer's diary, and the academic thesis to create a philosophical fiction of hope about literature. In its way, it even overlaps at the edges with the abstract, experimental fiction of the Australian writer Gerald Murnane.

Technically playful, Vladislavic employs formal devices like a foreword, afterword, footnotes, and epilogues to append humour or strange facts to each chapter. This adds to the curatorial tone, which is apt since he says he's tried to create a delicate "leporello" from a mountain of raw material. "There were hundreds of failed stories to choose from," he says, then adds humbly that this doesn't make him unique. "Presumably most writers have many more ideas than they are able to act on, and the number of stillborn schemes and incomplete drafts in my files is not unusual."

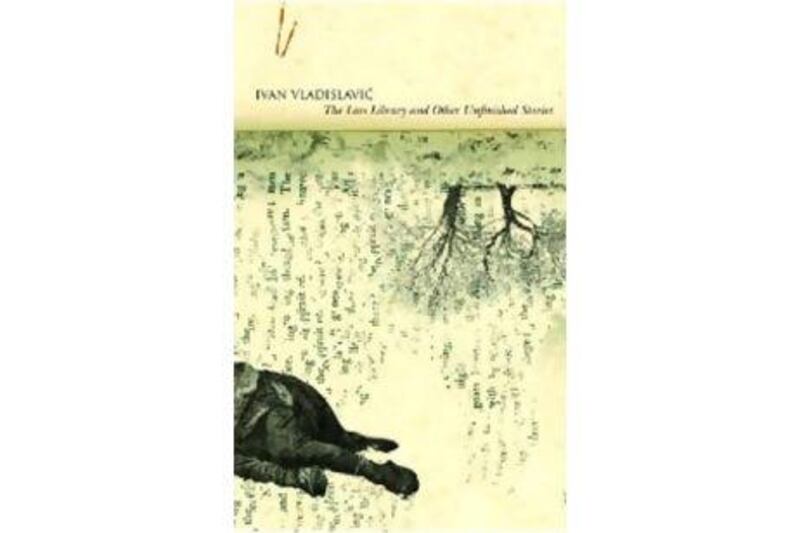

There's diversity among the failed story ideas, or "unsettled accounts", he's chosen to present: a married couple on a herpetological expedition to the Lesser Sunda Islands, an Oulipo-inspired novella based on the number 12 with 12 chapters of 12 paragraphs and 12-word sentences, "a story built around a series of friezes", a woman who's too distracted by the Cartoon Network to finish her novel, and a story about "the menagerie of creatures seen only in the dictionary". Each piece is also accompanied by one of Sunandini Banerjee's fine illustrations that parallels the gloom or whimsy of the topic.

The topics serve as entry points to more serious digressions that slowly and carefully twine around the themes of loss and absence in art. In the introduction, Vladislavic recounts a few key historical events that took place during the years he failed to write these eleven pieces. For a time, he says he imagined himself to be "some sort of historian". But violent incidents in history seem to act upon him like an enervating force. Rather than inspiring, they cause despondency. He notes for instance that among other major political upheavals that have taken place during his lifetime, "the four years between February 1990 and April 1994, when the historic first democratic elections took place (in South Africa), some fifteen thousand people died in political conflict". He later addresses genocide, colonialism and racism in different forms through history as they affect the course of human life and art.

In trying to write a story called The Last Walk, "about the last days of a writer", Vladislavic's thoughts lead to humanity's occasional indifference to death. He begins with an interest in a famous photo of Swiss writer Robert Walser dead in a snow bank. "[He] is lying there supine, with his head bared and his hat tilted on its brim, and nothing expresses the fact that he is dead more coldly than the space between the two." But other worries soon intrude. "Did the photographer himself set up his tripod at a cool distance and take his photograph without even approaching his subject to see whether he still breathed?" "[Did] no human rush to help the old man?"

His thoughts turn then to a "horrifying photograph", he admits, having looked at it "repeatedly, with clinched morbid curiosity", of Yugoslavian men hanged by the Nazis and how one of the dead, unlike Walser, has his hat securely atop his head. "I wanted to write a story about the last days of a writer," Vladislavic says, "but I am preoccupied with hats." This is humour deflecting the observer's anguish. To explain why he ultimately could not write The Last Walk, Vladislavic says only of Walser, "Clearly he is not the true subject of my story and that is why I cannot finish it." He doesn't state what his "true subject" is, and what's left unsaid becomes the point. Instead, he describes how he later searched online for the name of the photographer who took Walser's death photo, but this yielded only more photos taken from new angles. "A drift of information slides out of the monitor, burying my hands on the keyboard."

The title short story, The Loss Library, is placed at the book's centre. It's a fantasy in which an attractive librarian leads a writer through rooms full of great books "that would have been written had their writers not died young", others whose "authors lost faith in them and turned to other things", volumes that "once existed but were lost for one reason or another", and "books that came to their authors in dreams and were forgotten in the light of day".

When the narrator asks her the obvious question, "May I look at one of them?", she responds, "Oh no! That's not allowed at all ... Open one of them, let its influence be felt for a moment, and a line or two might change in all the world's libraries."

It's a nice enough story, but it doesn't convey a real sense of loss, even though Vladislavic invokes the idea of lost works by Franz Kafka and James Joyce.

The story is important only as a fuse in the text to ignite other ideas later on. This occurs in Cold Storage Club, a failed story about wealthy bibliophiles who preserve their personal libraries in immense freezers. In it, the earlier motifs of hats, snow and photographs reappear. Then Vladislavic mentions a 1933 Nazi book-burning in Berlin, and then brilliantly tells of the snowy day he visited Micha Ullman's haunting underground installation in Berlin built to remind people of the 20,000 books lost to fire that day. We've moved in a few pages from lost fiction about frozen libraries, to truly lost books, to a frozen day over an empty art installation created by "an artist of the absent", as he calls Ullman, to commemorate the loss.

Vladislavic writes with a passion about his subjects that incites concision. With the thematic unity he's established, we come to see his assemblage of personal losses as part of wider losses of art throughout history, though he never says so. Thus, this odd book accrues a richness at having covered both personal and historical ground within the territory of the author's mind.

"Am I telling the truth," says the narrator at one point during the title story, "or just trying to charm her?" Ostensibly, he's talking about the attractive librarian. But he could also mean time, history, or fate, and the question echoes throughout the book, asked by a writer who continues to feel the absence of these unfinished stories in his creative life, grasping at the shape and meaning of certain empty places within himself.

Matthew Jakubowski is a writer and a fiction judge for the Best Translated Book Award.