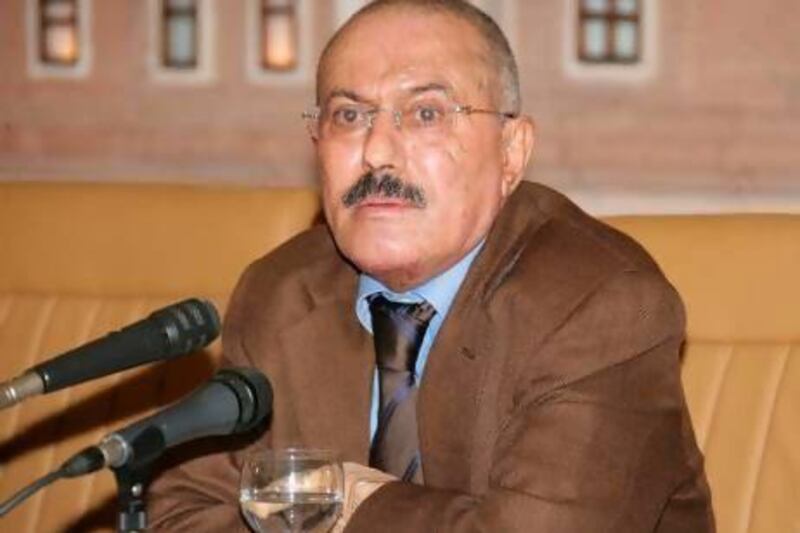

Yemen has a history of lopsided elections. Under former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, 90 per cent blowouts and fraud-riddled votes were the norm. In one of the more egregious examples, Mr Saleh's opponent even announced that he too would be voting for the incumbent. But until last year, Yemenis had always had a choice. Even if it was just "yes" or "no".

In February 2012, Mr Saleh's long-serving vice president, Abdrabu Mansur Hadi, took over the presidency in a process capped by a strange referendum-like vote, in which Yemenis were confronted with a single name and only the "yes" box. The one-man election was the result of an international deal put together by the US, the UN and regional GCC countries. Most Yemenis seemed happy to finally have a president who wasn't Mr Saleh, but they were less pleased with the immunity clause, which the international community believed was necessary to convince Mr Saleh to step down and to avoid a Syrian-style civil war.

One year after what was billed as a "historic vote", hopes for the new Yemen that protesters thought they had won are quickly disappearing in the face of a crumbling economy and a worsening political situation. Student activists in Sanaa's Square of Change are disheartened and disorganised. The sectarian situation has once again turned ugly and, in places violent, particularly the continuing clashes between Islah supporters and Huthis in the northern highlands.

Yemen is a broken country and no one - not the US, Saudi Arabia or any of the varied Yemeni factions - has the strength to put it back together again. Outsiders like the US are more concerned with fighting Al Qaeda than with rebuilding, and the Saudis have always worked to keep Yemen divided and dysfunctional. None of the Yemeni power groups have enough strength to impose their will upon anyone else, but most of them have enough guns and men to act as a spoiler.

The problem today remains what it was a year ago: the deal that brought Mr Hadi to power was less a solution than a mechanism to buy time. None of the key issues were addressed and, more importantly, none of the country's various armed factions were dealt with. Everything was pushed off to the future in the blind and desperate hope that a national dialogue would arrest the country's disintegration. That has not happened.

Mr Hadi has taken some steps to reform the military, but he remains too weak to directly confront the two individuals that matter most: Ahmad Saleh and Ali Muhsin Al Ahmar. The former is the former president's eldest son and the latter a fellow tribesman who broke with the elder Mr Saleh during the uprising. Both have carved out their own personal fiefdoms in the military, and Mr Hadi has used one to balance the other. But until he is able to rid himself of both he won't be able to unify the military and from there rebuild a ravaged country.

As one Yemeni official told me recently: "Without Ali Muhsin, Ahmad would eat Hadi; without Ahmad, Ali Muhsin would eat Hadi."

Even Mr Saleh is still an issue. Unlike the other Arab presidents forced out of office as a result of the 2011 uprisings, Yemen's former president hasn't been pushed into exile, prison or the grave. Instead he remains a force on the Yemeni political scene, both by leading the General People's Congress, the political party he created, as well as through the continued loyalty of family members like his son along with other clansmen who continue to occupy high positions in the military.

There are other concerns as well. Nearly a year into his presidency Mr Hadi has yet to appoint a vice president, a dangerous oversight in a country that has had five presidents, none of whom left on their own terms. Three, including Mr Saleh, have been forced out and two others were assassinated. The people Mr Hadi does appoint tend to be family members and long-standing friends, sparking concerns that he could morph into a Mubarak-like figure: a little-known vice president who once in office refuses to yield power.

National Dialogue, the great political hope of the international community, has been delayed numerous times and the latest start date is now set for March 18, the anniversary of the bloody Karama crackdown in which 45 protesters were killed by snipers loyal to Mr Saleh.

Few in Yemen seem to think the National Dialogue will work or bring about any sort of a lasting political settlement. Not all of Yemen's various factions have yet agreed to participate, but even if they do, there are long-standing and near-intractable grievances that are unlikely to be resolved quickly. What happens if national dialogue doesn't work is a question that is ignored as inconvenient.

Halfway into what is supposed to be a two-year transitional under Mr Hadi, Yemen is no closer to a political solution than it was when he first took office. He has one year left. The clock is ticking.

Gregory D Johnsen is the author of The Last Refuge: Yemen, Al Qaeda, and America's War in Arabia

On Twitter: @gregorydjohnsen