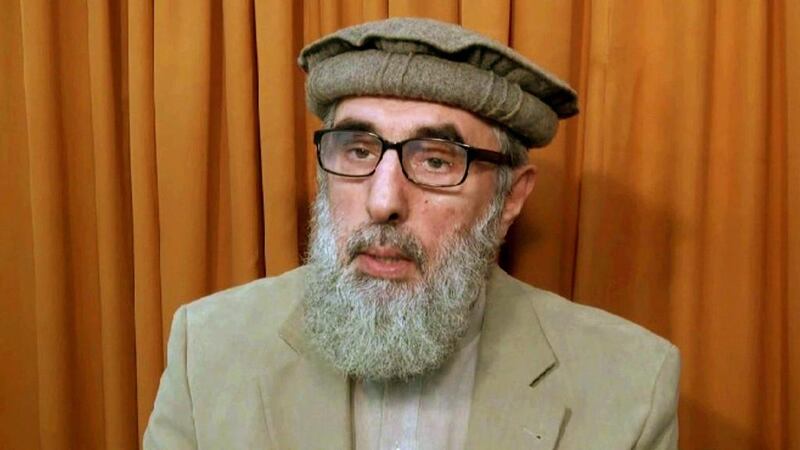

Kabul // For more than three decades, the Afghan warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar has operated as a surreptitious fighter, warring against a succession of foes: the Soviets in the 1980s, mujaheddin groups, his country’s government, international troops.

Hekmatyar’s brutality towards Afghan civilians made him the scourge of human-rights activists working in Afghanistan. His whereabouts have been unknown for years.

But after the UN removed sanctions against him last week, the warlord can finally return to the public stage in Afghanistan and begin an unexpected process of rehabilitation: an entry into active politics.

The UN’s implicit pardoning of Hekmatyar came at the urging of the Afghanistan government, which last September agreed to a peace deal with Hekmatyar and his militant group Hezb-i-Islami.

Human-rights groups have been quick to criticise Hekmatyar’s rehabilitation. The New York-based Human Rights Watch called him “one of Afghanistan’s most notorious war crimes suspects”. By admitting him back into the public sphere, it said, the government was compounding “a culture of impunity” that was denying justice to victims of war crimes.

But Farooq Bashar, a political analyst at the University of Kabul, said Hekmatyar’s return could further the peace process and encourage the government’s negotiations with other groups such as the Taliban.

Talking about war crimes suspects in the present climate was futile, Mr Bashar told The National, because “90 per cent of them are part of the regime and serving in high positions”. If the courts have to begin acting against anyone, they must first act against suspects in Kabul, rather than those in the outlying provinces, he said.

With Hekmatyar’s peace deal, “there was no offer of [official] posts, money or power-sharing. The peace was being made just for the national interest, and this peace will be stable and effective.”

The Hezb-i-Islami Afghanistan (HIA), a moderate breakaway faction of Hekmatyar’s group, called the removal of sanctions “a big step”.

Haji Atiqullah Safi, a member of HIA, said arrangements were already being made for Hekmatyar’s return to Kabul, expected towards the end of this month. “A house is being taken for him, an office is being taken for him. The government is arranging security for him.”

Mr Safi expected Hekmatyar and his colleagues to merge with the HIA, and said that the newly enlarged party would press for the release of some of its members who are political prisoners. “Very soon, a delegation of our party will start a visit of Islamic countries” to establish formal diplomatic links with other governments, he said.

Mr Bashar said he expected the HIA to fare well whenever it next competes in elections. But other analysts described the party’s prospects as less certain.

“I anticipate Hekmatyar’s return to active politics, but given his Pashtun ethnicity and bloody past that included the indiscriminate shelling of civilians, it remains to be seen how the situation will unravel,” said Arushi Kumar, a researcher at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in New Delhi. “Given his unpredictability in the past, it is uncertain whether the Afghan people will be willing to forgive his brutal actions to make way for more talks.”

Gulshan Sachdeva, a professor of political science at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, suggested that Hekmatyar’s return was useful only to the governments of Afghanistan and the West, which are “desperate to show that the peace process is still possible”.

“This is particularly important as most western forces have already moved out of the country and the security situation is still very difficult,” Mr Sachdeva said. “With the peace process with the Taliban in disarray, bringing Hezb-i-Islami Gulbuddin into the mainstream can indicate that the government is serious about political negotiations.”

But the Afghanistan of 2017, Mr Sachdeva said, “is very different from the Afghanistan of early 1990s and of 2001.”

“There is a new generation of Afghans who have grown up in a relatively peaceful and democratic country, with hopes for the future,” he said. “I seriously doubt if Hekmatyar could connect to the new realities of today’s Afghanistan.”

It is possible that the government will accord Hekmatyar “some token role” in its establishment, to prove its inclusiveness and earnestness, Mr Sachdeva said. “Beyond that, I don’t see Hekmatyar playing any major political role in present-day Afghanistan.”

foreign.desk@thenational.ae