WASHINGTON // Private war crimes investigators say they have a case to try ISIL’s leaders over the kidnapping of thousands of Yazidi women as sex slaves in 2014 as well as other crimes against humanity in Iraq, but cannot get the global backing needed for an international tribunal.

The Commission for International Justice and Accountability, an independent investigative group, as well as US diplomats, said the Obama administration has done little to pursue prosecution of the crimes that secretary of state John Kerry has called genocide against the Iraqi minority.

“The West looks to the United States for leadership in the Middle East, and the focus of this administration has been elsewhere – in every respect,” said Bill Wiley, the head of the commission.

The US has no legal obligation to take on the genocide of the Yazidis, but president Barack Obama has said that “preventing mass atrocities and genocide is a core national security interest and a core moral responsibility of the United States of America”.

Stephen Rapp, who stepped down as the Obama administration’s ambassador at large for war crimes last year, said the US should have moved early to help secure evidence of ISIL atrocities and push for the creation of special Iraqi courts to try war crimes.

“The priority for the US government is to win the war against [ISIL] and destroy them,” Mr Rapp said. “It’s been profoundly disappointing, because the idea of accountability has been such a low priority.”

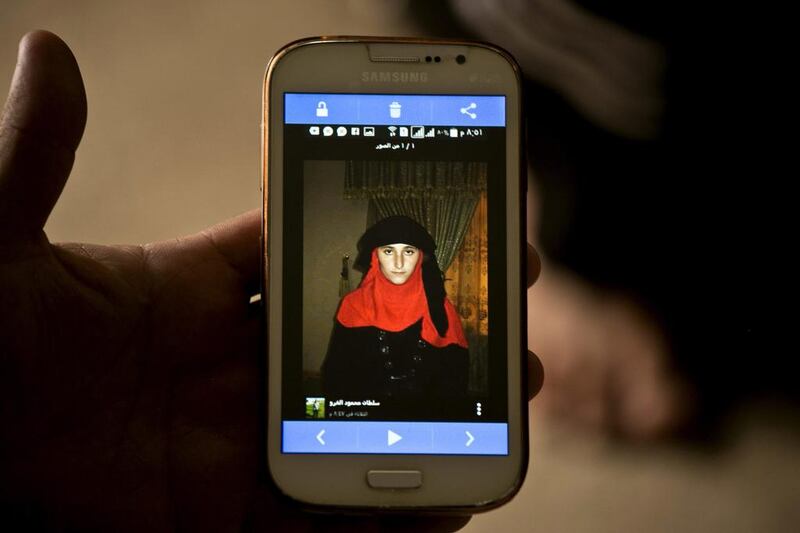

Mr Rapp is now the chairman of the advisory board of the commission, whose investigators in Iraq work with the Kurdish regional government to document ISIL’s crimes, including those against the Yazidis. They have built a case implicating the entire ISIL command structure in a plot to kidnap Yazidi women and girls and establish a sex-slave market.

The plan was executed by an organised bureaucracy at every step along the way, from the temporary sorting facilities – including a prison, schools and a curtained ballroom where the Yazidis were divided by age and willingness to convert to Islam – to the waiting buses that would haul them by the dozens across the border to Raqqa. ISIL’s shariah courts soon stepped in to settle contract disputes and ensure that its finance hierarchy got its cut of the sex-slave proceeds.

“You have members of ISIL who were engaged in ensuring that this system continued and that it functioned well,” said Chris Engels, an American lawyer who is leading the commission’s legal investigation. Without a legal documentation of their identities from the top down, many could “slide into refugee streams” and disappear, he said.

Though there are at least dozens of ISIL extremists in custody in Iraq, there have been no prosecutions for the crimes against humanity that the US – among many others – insists have taken place. On Tuesday, the US envoy for the coalition to counter ISIL, Brett McGurk, tweeted that he “pledged full accountability” for ISIL crimes against the Yazidis, whom the extremists consider infidels because of their religion.

Although the US has backed limited efforts to secure evidence of ISIL atrocities in Iraq, there have been few tangible steps toward prosecution.

The war crimes commission is best known for collecting evidence against Syrian president Al Bashar Assad but branched out to document atrocities committed by ISIL and other extremist groups. A staff of 20 in Iraq, split into three teams, collects evidence that is analysed at the group’s main offices in Europe. Investigators have pored over hard drives, leaked documents, phone records and interviews with captured ISIL fighters, in addition to monitoring the extremists’ propaganda.

The commission says its legal file, painstakingly and often perilously gathered since 2014, is the answer to calls for ISIL extremists to face justice beyond coalition air strikes. But it is ready for a court that does not yet exist.

Neither the US nor Iraq is a party to the International Criminal Court in the Hague, which is a court of last resort when national judicial efforts have failed.

A measure by the house of representatives that calls on the US to fund precisely the kind of court envisioned by the war crimes commission is unlikely to advance anytime soon in an election year. With full international backing, the commission says it would need about $6.6 million (Dh24.2m) and about six months to get the trials going.

It hopes to turn an existing court in Erbil, the Iraqi Kurdish capital, into an internationally backed court for ISIL members.

But whether the courts of Iraqi Kurdistan, where most ISIL prisoners are kept, are ready for the complexities of international criminal law is an open question. US officials worry that backing a special court in Iraqi Kurdistan raises sticky questions of sovereignty with the Iraqi central government in Baghdad, which is suspicious of Kurdish independence efforts.

Mr Wiley said the commission’s goal was transforming the evidence it had gathered into prosecution of ISIL members.

“Through a scrupulously fair trial, you illustrate that these guys are not soldiers of Mohammed,” he said. “These are the leaders of a criminal syndicate.”

* Associated Press