LONDON // In a tiny room just inside the lobby of one of London's largest mosques, security staff were huddled around a single computer monitor discussing where best to focus their gaze.

Trying to make sense of feeds from 26 closed-circuit TV cameras on a single screen was not the only challenge faced by the three young men on duty Tuesday night at the East London Mosque.

"The problem with CCTV," said Mohammad, 23, the only salaried staff of the three, none of whom would give their family names, "is that every one looks suspicious."

That assessement is not just the effect of grainy footage.

Ever since the murder last month on a London street of a British soldier, mosques and other Islamic institutions in Britain have been on high alert.

They have reason to be. The hate crime monitoring site, Tell Mama, has received more than 200 reports of anti-Muslim incidents across the country in the three weeks since the soldier, Lee Rigby, was killed in Woolwich.

Two Muslim men, Michael Adebolajo, 28, and Michael Adebowale, 22, announced to passers-by that the gruesome daylight killing was in revenge for British military action against Muslims in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Fourteen mosques have been vandalised in attacks ranging from offensive and largely sacreligious graffiti to arson.

Last Wednesday, not far from the Tower Hamlets area of London where the Eeast London Mosque is located, a small Islamic centre catering to the Muswell Hill area's Somali community was set ablaze in a suspected arson attack.

Just three days later another fire erupted at an Islamic boarding school in Chislehurst in South London, prompting London's police commissioner, Bernard Hogan-Howe, to step up security around other potential Muslim targets across London.

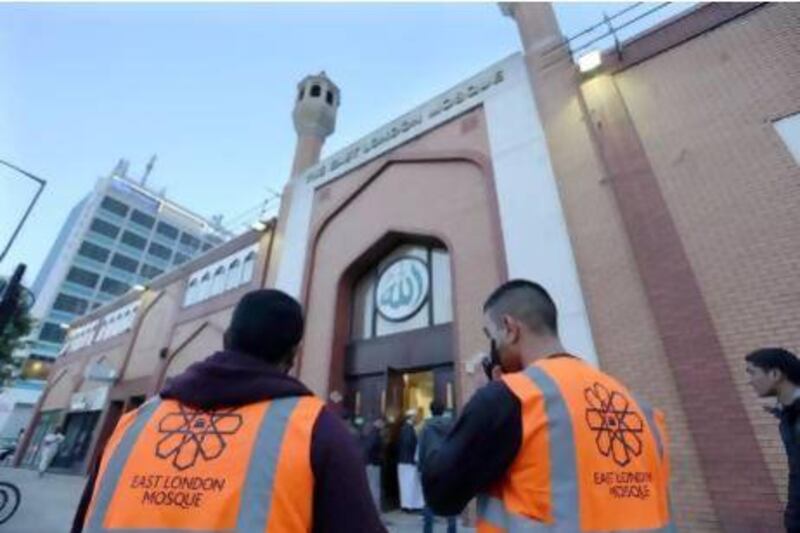

Outside the East London Mosque, which averages some 6,000 worshippers for Friday prayers in a borough that is majority Muslim, two uniformed Tower Hamlets police officers now take up prominent positions all day, every day.

Chief Superintendent Dave Stringer, the borough police commander, said that since Woolwich there have been between 20 and 50 extra patrols throughout the borough, which has about 40 mosques and Islamic institutions.

It has been a drain on resources, acknowledged Mr Stringer, who commands 650 officers. And it has been a challenge to strike the right balance.

"Some of the police work has been very low key," Mr Stringer said in a phone interview. "We don't want to frighten the local community. But sometimes it is better to be more visible. Now is such a time."

There is constant coordination with community leaders, including officials at the East London Mosque, he said. A decision was taken at the mosque soon after the Woolwich killing to augment the existing security staff, and volunteers were recruited to help patrol the large building, which includes administrative offices, a gym and a school.

Every night since then, seven young men - two of whom are paid a part-time wage - have taken turns to guard the mosque.

The volunteers received some basic training, mainly to ensure they understood their roles and their limits, said Juber Hussain, head of mosque security.

"They are not there to confront people, whatever their instincts. First, they are there to be visible. If something suspicious happens, they should alert management or, if it is an emergency, direct to the police."

Their presence has been welcomed by local police.

"These are not vigilantes," Mr Stringer emphasised. "They provide up-to-date information. We do the policing."

Armed with walkie-talkies and dressed in bright orange reflective vests emblazoned with "East London Mosque Staff", the volunteers make a circuit of the complex every hour after evening prayers and until the Isha prayers at night.

Around one in the morning the building is locked, and the guards make one last round to check that all doors are secure. Then they move inside the mosque and huddle in the room off the lobby, trying not to be fooled by the grey and grainy footage that casts everyone as a potential criminal.

Apart from a can thrown by a passing car, none of the three on duty on Tuesday night had any unusual incident to report.

Abdullah, 21, who is about to start a civil engineering course, said he had happily volunteered after Woolwich. Like Mohammad and Shah, 23, a computer science student who recently finished his exams, he had time to spare.

And like his friends, Abdullah told numerous stories of anti-Muslim incidents in recent weeks, accounts related to him by relatives, friends and acquaintances up and down the country.

One girl had had her veil pulled down in a bus. Another boy had had something thrown in his eyes that blinded him temporarily. Such reports of random abuse - verbal, physical or both - abound at the moment. They add to the men's own experiences, which predate the Woolwich killing.

Not far from the mosque Abdullah said he had been attacked himself one night last year, soaked by a bucket of water thrown from a passing van carrying three white men.

"'We don't want you here'. 'We don't like your kind'," he recalled the men shouting at him.

"I worry for the younger generation," said Shah, who said things were getting worse, even as first generation immigrants became second and third, and nobody anymore considers themselves "anything but British".

The East London Mosque has also seen a spike in hate mail, according to Salman Farsi, a spokesman.

One effort had clearly taken some time to prepare. It was postcard that featured a picture of a pig and a carefully printed offensive caption. Inside the envelope the postcard arrived in, a message read, in part, that, "we will continue p***ing on you".

A DVD was included, which from past experience Mr Farsi assumed contained pornography.

A pile of similar but unopened envelopes had gathered in his in-tray. He was in no hurry to open them. "It's too depressing".

Still, he said, the mosque too has been mindful of striking a balance between security and serving the community.

There is no security desk or uniformed security staff during the day. There are no metal detectors, and in daylight, the mosque remains open to anyone.

"We are not an airport," Mr Farsi said. "We are a place of worship. It has to remain that way."

okarmi@thenational.ae

UK Muslims feel the hate after soldier killing in London

Anti-Islamic attacks have increased since the brutal daylight assault on British soldier Lee Rigby on May 22.

More from the national