QUETTA, BALOCHISTAN // In a land with no shortage of armed extremists, the propaganda broadcast has a familiar look.

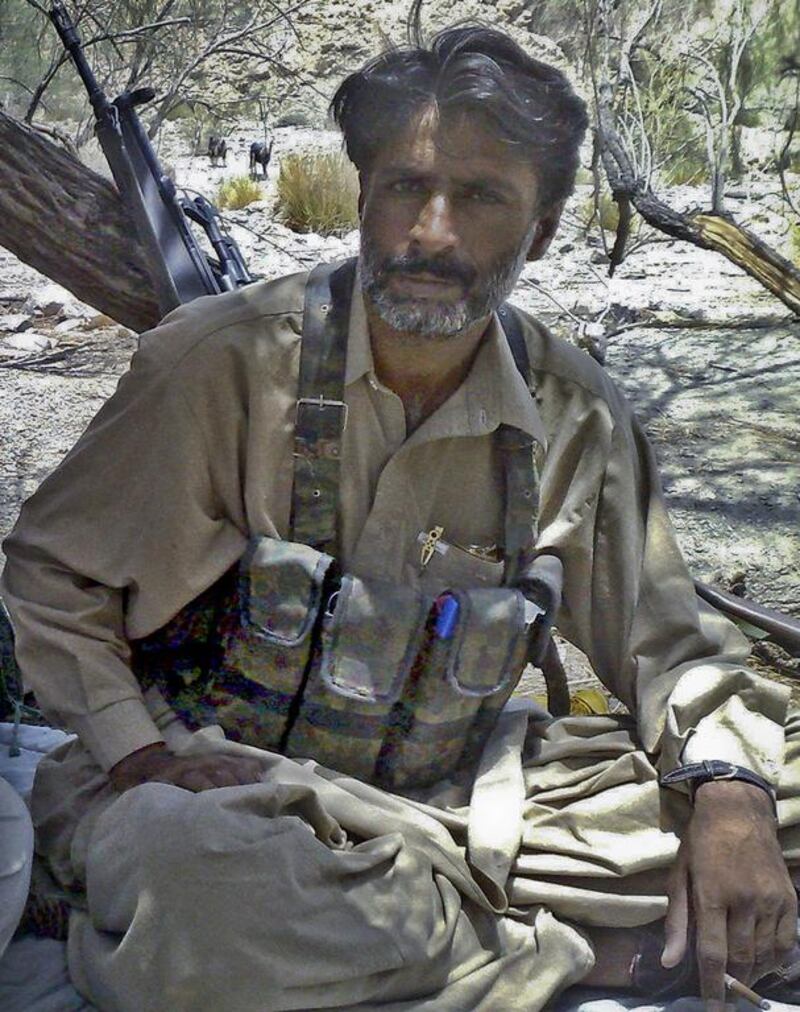

A fugitive militia leader talks to a camera from a hidden mountain location, taunting the government that previously claimed to have killed him, and vowing to continue the struggle.

But apart from the assault rifle by his side, Dr Allah Nazar’s messages depart from the usual script of Pakistan militant groups.

For one thing, he speaks in the educated tones of a man who was once a practising physician. And rather than preaching extremism, he lambasts it, criticising the Taliban and Al Qaeda with equal venom.

That, though, does not stop him being very high on Islamabad’s long list of wanted men. For a decade and a half, he has been the leader of the Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), which campaigns — and kills — for the independence of Pakistan’s vast south-western province.

A belt of searingly hot desert studded with mountain ranges, Balochistan used to be just another tribal backwater. For decades, complaints that it was marginalised and undeveloped went largely ignored, even when made at gunpoint.

Today, though, men like Dr Nazar stand in the way of one of Pakistan’s most important goals — the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, or CPEC — which will run right through their homeland.

The corridor will give the Chinese a much quicker route to the Arabian Sea, and should turn Balochistan’s moribund port of Gwadar into Pakistan’s Dubai.

As well as a 1,800km road snaking through the Himalayas from China’s western border, there will be high-speed railways, energy projects and new deep water docks.

The project — financed mostly from Beijing — is worth US$54bn (Dh198bn), potentially very welcome in a province with chronic water shortages and 50 per cent of households in poverty.

CPEC, though, is not just about money.

By offering itself as a shortcut to the West, Pakistan guarantees itself a strategic place in Beijing’s backyard, making it less likely to be bullied by India, its historical rival. Ministers have dismissed claims of “Sino-Pakistani” colonisation, saying it will bring prosperity that will end the Balochs’ sense of grievance.

“Why should Chinese industries not come to Pakistan when they are being set up in most countries?” asked Ahsan Iqbal, Pakistan’s planning minister, last week.

“The trade zones established under the CPEC project will create new jobs.”

For the separatists, though, it is not just the prospect of large numbers of Chinese workers arriving in Balochistan that unnerves them. Of more concern is that any jobs bonanza will be rigged to bring in hundreds of thousands of Punjabis from the rest of Pakistan, diluting the Balochi identity in the name of progress.

Already, construction zones for CPEC have turned into war zones.

Since 2014, at least 44 members of the Frontier Works Organisation, an army-run construction firm spearheading the work, have been killed by separatist bombs and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

“We are attacking the CPEC project every day,” Dr Nazar told Reuters last September, which also confounded Islamabad’s claims to have killed him in a raid the year before. “It is aimed to turn the Baloch population into a minority.”

Born in the impoverished town of Mashkay, Dr Nazar is one of a number of middle-class Baloch students who claim to have taken up arms as a last resort.

An admirer of the Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, he is an avowed secularist, seeing extremist groups like the Taliban and Al Qaeda as creations of the corrupt Pakistani government. But he has not flinched from shedding blood, nor have other armed separatist factions which co-operates with the BLF. Together, they claim to have killed up to 2,000 security force members, although the government puts the figure at nearer 1,200.

Dr Nazar’s freedom fighter image is hotly disputed by Anwar ul-Haq Kakar, the senior government spokesman in Quetta, Balochistan’s capital. He questions how anyone attacking CPEC workers can really have Balochistan’s long-term interests at heart, suggesting they are more interested in the opium trade from neighbouring Afghanistan.

"In my opinion this is a law and order problem, rather than an insurgency, and it's never gained much popular support," he told The National. "They get paid for allowing drugs to pass through the areas they control."

Verifying either version is not easy, however, as Pakistan has long been sensitive about letting outside eyes into Balochistan. America has long accused Quetta of giving refuge to the late Taliban leader, Mullah Omar, and however much Islamabad denies such claims, Quetta is usually off-limits to both western and local journalists. Human rights groups claim this prevents scrutiny of countless “disappearances” of Baloch activists — killings the government blames on intra-separatist feuds.

The National was allowed in this month as part of a government-organised trip, during which officials pressed home their claim that the insurgency was losing steam. Lt Gen Aamir Riaz, head of the army's southern command, pointed out that last year alone, some 800 fighters had surrendered under a government reconciliation scheme.

“Things should improve for Balochistan as development comes along,” he said. “I don’t say this place is perfect, but it isn’t Iraq or Syria.”

“The separatist terrorists are as bad as the religious ones,” added Sharif Hadim, 23, a trader in the local market, where anti-terrorist police mount regular patrols.

Still, while Dr Nazar might be feeling increasingly lonely in his mountain hideouts, grievances of the Balochs remain, says Sana Baloch, of the more moderate Balochistan National Party. He warns that if CPEC leads to Balochistan being overrun with outsiders, it will turn Gwadar not into another Dubai but another Karachi, Pakistan’s other big port city, long notorious for its inter-ethnic violence.

“I have no sympathy for the armed groups, but we fear the coastal region will be taken from the hands of Baloch people,” he said. “For the last 40 years, Balochistan has been completely in Islamabad’s control, and used as a dumping ground for political garbage. That must end.”

foreign.desk@thenational.ae