Ender Ozgur has lived an American life for the past 25 years. He likes to be known as Andy and runs a fast food chicken restaurant and grocery store at the far end of Manhattan Island.

But for four days in the past week he has left the running of his business to his partners, instead making the 45-minute commute south on the A train to the federal courthouse in lower Manhattan in time to find space on the public benches.

He is one of dozens of members of the Turkish diaspora who assemble each morning to watch the trial of a banker accused of violating American sanctions on Iran.

Each gives the same reason for taking a seat.

“I come because I’m Turkish,” is how Mr Ozgur put it on a recent weekday afternoon.

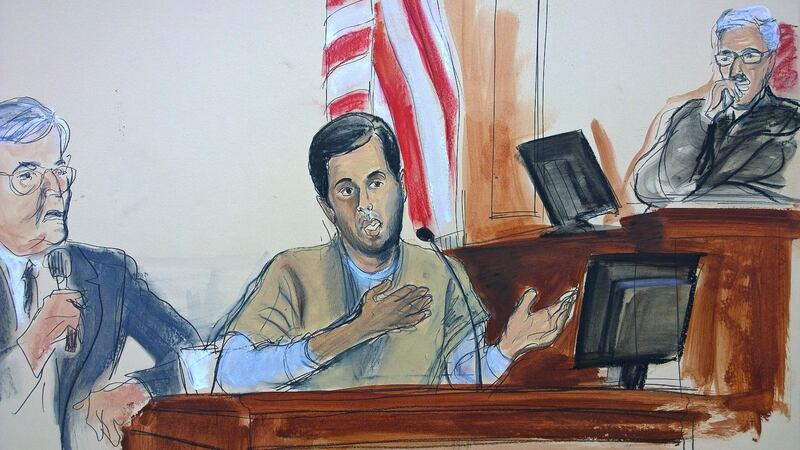

Mehmet Hakan Atilla is accused of using his position at Turkey’s state-run HalkBank to design a system of money transfers to help Iran access cash.

The case is shining a light on some of the darkest reaches of the Turkish government, exposing allegations of bribery and corruption hidden behind front companies and fake deals that prosecutors say reach to the highest levels of government.

The prosecution’s main witness has been giving evidence for the past week. Reza Zarrab, a 34-year-old gold trader who has already pleaded guilty to his role, described bribing a government minister and claimed that Recep Tayyip Erdogan signed off on the involvement of two Turkish banks when he was prime minister.

New York’s federal court is picking up where the Turkish courts left off. At the end of 2013, Zarrab was swept up by Turkish authorities in a corruption probe.

Mr Erdogan dismissed the investigation as a “judicial coup” plotted by supporters of Fethullah Gulen, a cleric who lives in Pennsylvania but whose social movement is blamed for last year’s attempted coup.

Zarrab was released after 70 days and Mr Erdogan launched a purge of Gulenists from the police and judicial system.

For Turks in New York, the trial offers a chance to find out the real story.

“The court at home said it was all lies, it wasn’t true. But I trust this federal court,” said Mr Ozgur from his position in front of twin TV screens beaming the evidence to watching members of the public in courtroom 12D. “Now I want to see who’s telling the truth.”

_____________

Read more:

_____________

Such has been the intense interest that not only has the 17th-floor courtroom been filled to capacity every day, but officials had to add extra chairs to cope with demand in the overflow room five storeys lower.

Alongside members of the Turkish press corps sit language students in jeans and workers dressed for the city. Some take notes while others simply soak it all in.

The high stakes and big characters mean the trial has already taken on an air of political theatre – part Law and Order, part West Wing.

There were gasps when Zarrab described how he may have made as much as $150 million from his cut – although he couldn’t quite remember the exact number.

And there was laughter when some of his telephone conversations were played for the jury, sending colourful Turkish curses echoing through the wood-panelled courtroom.

The jury has also heard how he was released from federal jail after being attacked by a man with a knife.

At times Atilla seemed like a bystander at his own trial, with attention focused on the young millionaire witness as he implicated government ministers, a network of banks and Mr Erdogan.

“It’s like a soap opera – you want to know what happens tomorrow – but this is all real and it’s all about us … and not in a good way,” said one woman who has been a fixture in the overflow room since the trial began.

She said she had lived in New York for five years after arriving to study English but asked not to give her name for fear it would cause her problems back home in Turkey.

The tensions and suspicions, she said, were evident among the audience. She described how other attendees were quietly probing each other with questions as they worked out who was who: media or activist, government or Gulenist.

“There were people taking photographs of everyone leaving the courthouse the other day,” she said with a shiver.

Attending in person is the best way to get the full story, she added. Even journalists admitted they self-censored their reports to avoid repercussions from a government that is increasingly intolerant of dissent.

The main draw has been Zarrab. He answered questions in an earnest, patient manner, displaying the sort of charisma that made him a financial player in Turkey and won him a pop star wife.

“I used to hate this guy but I don’t any more,” said Mr Ozgur in his gently accented English. “He was just doing business. It’s the people he bribed - they are the ones I really blame.”

The prosecution contends that Mr Atilla, the banker whose day job it was to understand international laws and sanctions, was the architect of the scam.

Not many in the audience are buying it. They see bigger, broader forces at work.

A finance worker who stopped by for one of the afternoon sessions said there had been little evidence to directly implicate Mr Atilla so far.

“This is big money and international politics,” he said before hurrying off to his next meeting. “Atilla is just the pawn.”