POOLER, GEORGIA // David Dickey paused for effect, laser pointer primed, eyes seeking out individual members of his audience.

"It's all here, in his own words," the Savannah attorney said, eyes resting for a minute, quietly intense, before his voice rose again, punching out the main tenets of his argument.

"We have a confession of war crimes carrying with it summary punishment according to their own rules. Yet this general is feted as a war hero, not tried as a war criminal."

Mr Dickey's voice rose further still, taking on the rhythmic lilt of a practiced fire-and-brimstone preacher.

"This was a United States of legalised terror, guided by the un-Christian idea that might makes right."

Mr Dickey rested his case to applause. The audience of about 40 people on Monday night, mostly members of the Savannah Militia Camp 1657, a chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, did not need much convincing that William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union general Mr Dickey had just spent more than an hour excoriating should be viewed as a war criminal.

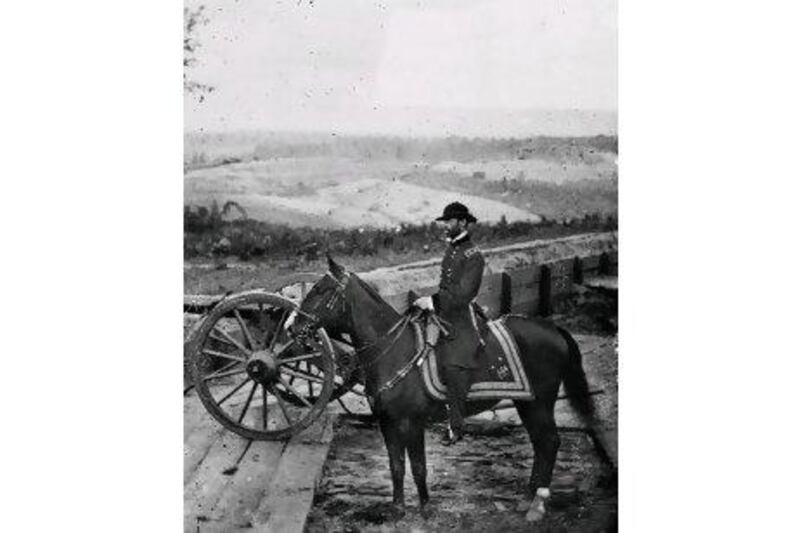

Maj Gen Sherman is here known as "the devil", a man who, with unwarranted cruelty they argue, fought a war that 150 years ago threatened to permanently rupture the fledgling United States. It is a far cry from the traditional understanding of the American Civil War as one fought primarily over the principles of unity and opposition to slavery, as underscored by Barack Obama, the US president, on Monday.

"We are the United States of America. We have been tested. We have repaired our Union, and we have emerged stronger," Mr Obama said in a presidential proclamation on the anniversary of the start of the war on April 12, 1861.

He urged Americans to engage in activities that "honour the legacy of freedom and unity that the Civil War bestowed upon our nation."

But here, in the Western Sizzlin Steak House in Pooler, about 10 km from Savannah, Georgia, the descendants of those who fought on the losing side continue to be passionately aggrieved at what they consider a misrepresentation of history.

Fought mainly in the South, the reverberations of the American Civil War are still felt keenly, and not just among the 109 members of Militia Camp 1657. Sherman marched from Atlanta to Savannah in 1864, leaving a swath of destruction in his wake to finally break the Confederacy's ability to wage war, a concept of "total war" that has left its mark on all subsequent warfare.

In December 1864, Sherman reached Savannah, which surrendered, sparing the city destruction. It was his "Christmas present" to Abraham Lincoln. But in the city today, defiant reminders are nearly everywhere.

A menu at the Vic's On The River restaurant refers to the "War Between States." A caption at the Savannah Visitor's Center and Museum talks about a captured Union ship that was re-fitted to become a Confederate iron-clad and "proceeded to kick Yankee Butt".

It is a defiance that rejects the notion that slavery was central to the war.

"After the war, the education system instilled the idea that the war was first and foremost about slavery," said Don Newman, commander of Militia Camp 1657. Mr Newman, 64, a former US marine, said he did not deny that slavery was a part of the equation. But he rejected as propaganda the notion that the North fought the war primarily to free the South's nearly four million black slaves.

Militia Camp 1657 and many similar chapters, he said, exists to correct this view of the war and properly "honour the legacy of the Confederacy and those who fought for it".

These included Joseph Jackson Todd, the great-great grandfather of David Todd, 61, a retired civil servant. Mr Todd carries his ancestor's faded picture in his wallet, taken hours before the battle at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, exactly 150 years ago, the first battle of the war.

The elder Todd survived and went on to prosper again even though he lost all of his property in the war, said Mr Todd. He lies buried, at his own request, with the two slaves he owned at the time, John and James, who had refused to leave Joseph, and fought by his side in the war, said Mr Todd.

The idea that the war was about slavery was a "crock", Mr Todd said. The war was about "limits on federal power and states' rights".

"You can dress it up any way you like", said Hari Jones, curator of the African-American Civil War Museum in Washington. "States' rights? States' right to do what? To maintain slavery. That was at heart what this was about."

The attempt to define the war away from slavery is an attempt to place the losses suffered by the South in the context of a noble cause even if in a losing one, said James McPherson, a Pulitzer Prize winning Princeton historian.

"Once slavery enters into the equation, it's pretty hard today, in 2011, to defend the Confederate heritage. That's why I think there's a kind of denial that slavery was at the core of the Confederate cause."

However, Professor McPherson would be part of a group that Mr Dickey decried as "high-class Harvard historians of Puritan extraction".

"Was Sherman's actions [in marching across Georgia] Christian? No. Did he know right from wrong? Yes. What's the opposite of a Christian? An anti-Christ. The devil," Mr Dickey said.